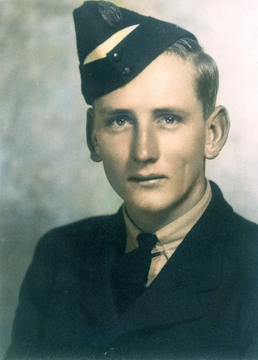

LEARMONTH, Ian Thomas McEwan

| Service Number: | 430695 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | 26 February 1942 |

| Last Rank: | Warrant Officer |

| Last Unit: | Not yet discovered |

| Born: | Cohuna, Victoria, Australia,, 10 June 1924 |

| Home Town: | Numurkah, Moira, Victoria |

| Schooling: | Katamatite State School, Victoria, Australia 2069 |

| Occupation: | Dairy famer |

| Died: | Shepparton, Victoria, Australia, 14 February 2001, aged 76 years, cause of death not yet discovered |

| Cemetery: |

Numurkah General Cemetery, Victoria |

| Memorials: | Numurkah Saluting Their Service Mural |

World War 2 Service

| 26 Feb 1942: | Enlisted Royal Australian Air Force, Warrant Officer, 430695 | |

|---|---|---|

| 23 Oct 1945: | Discharged Royal Australian Air Force, Warrant Officer, 430695 |

Help us honour Ian Thomas McEwan Learmonth's service by contributing information, stories, and images so that they can be preserved for future generations.

Add my storyBiography contributed by Stephen Learmonth

In 1921, the Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom and their Dominions met at the 1921 Imperial Conference. The discussion between heads of state would have far-reaching implications for the world and the future of the Learmonth family. Ground rules were established for what would become the Empire Settlement Act, whereby England was to supply people and Australia the land. British civilians and ex-service personnel were to be assisted in taking up residence in the underdeveloped and underpopulated Dominions.

Bill Learmonth may have seen this as an opportunity for his new wife, Catherine, and two-year-old daughter, Catherine Margaret. In early 1922, Bill embarked on the Orient liner SS Ormuz. Upon arriving in Melbourne on April 26, 1922, Bill Learmonth headed north to the rural district of McMillans in the Torrumbarry irrigation area, six kilometres southwest of Cohuna.

It’s interesting to take a breath and look more closely at the ship that brought William to Australia. The Ormuz began as the SS Zeppelin, a steamer intended to operate on the Bremen to Baltimore run. She was completed and handed over to her owners in early 1915, but due to the First World War, the owners, Norddeutscher Lloyd, decided to keep her safely laid up until after hostilities. After the war, she was renamed the USS Zeppelin and used as an American troopship for 19 months, returning Doughboys home. In 1920, after an extensive refit, she was renamed the Ormuz and placed on the London (Tilbury) to Australia migrant service. In 1927, NDL repurchased the Ormuz, refitted her, renamed her the SS Dresden and put her on the Bremen to New York route. In 1934 the Nazi Kraft durch Freud (Strength through Joy) Organisation chartered her for cruises for loyal Nazis who needed a holiday. On her maiden voyage, she struck a rock off the Norwegian coast and partially sank. Four lives were lost.

Bill worked as a labourer and share farmer in northern Victoria's dairy industry. Catherine and Cath joined Bill in 1922, emigrating on the SS Ballarat. A son, Ian Thomas McEwen Learmonth, was born at the Cohuna Hospital on June 10, 1924. In December of that year, the family moved to their farm on Meade’s Road near Katamatite, Victoria, which they called Glendevon, after a place in Scotland.

Newspaper accounts during the 1930s provide a snapshot of the different agricultural activities that Bill was involved in. In November of 1930, the Numurkah Leader included an advertisement that said, “Messrs Bartlett and Learmonth of Katamatite (‘phone 28), advertise in this issue that they are preparing to undertake wheat grading for district farmers. They carry with them a separator that is guaranteed to remove 99 per cent of wild oats.” Owning a farm in an irrigation district included many regular tasks. In mid-November, the Numurkah Leader reported on the monthly meeting of the Tungaham Council. One of the items stated, “From W. Learmonth, Katamatite, stating that owing to the table drain containing water, he was unable to do the work allotted to him by the engineer. He would not be able to complete the job until after harvest.”

In 1931, Bill and Catherine’s third child, Jeanette (Netta) Isobel, was born in Katamatite. Throughout their lives, Ian would refer to Catherine as “Sis” and “Netta” as Puss, as she managed to keep a menagerie of cats around the farm.

Ian’s many jobs around the area included tending the horse teams (up to 10 in one team), hay carting and stacking for friends such as Keith Curry and Bill Barfield, and picking sheep. Bill kept up to 40 horses on the farm, breeding four draughts and one light yearly. Ian recalled that he and his sister, Catherine, had milked three cows before school. Due to the extremely muddy conditions, they would milk in bare feet. The Learmonths had 20 milkers on the farm, and Catherine was generally responsible for milking them.

However, life was not all work. Catherine was heavily involved in the Country Women’s Association and the Presbyterian Ladies Guild. This often meant organising and attending functions, meetings and annual balls. The Youanmite CWA held its inaugural ball on Wednesday, July 21, 1937. As reported by the Numurkah Leader, among the female fashions was “Mrs Learmonth, black georgette and lace.”

The Learmonth family enjoyed various sports around the area, including tennis and golf. All were excellent golfers, with many wins and scores reported in the local newspapers. During the 1930s, Bill was the President of the Katamatite on several occasions. Like his parents and elder sister, Ian was a keen golfer, and often, he and his friends would choose one club each and go round the Katamatite Golf Course. The Golf Clubhouse would eventually be moved to Bill’s farm and serve as the family’s washhouse. Cath Junior also played basketball, which was more of a form of netball at that time. Ian was also a member of the Katamatite Cubs between 1933 and 1936.

In June 1938, a tornado struck the area. The event was reported in the Tuesday, June 28, 1938, edition of the Numurkah Leader, although they called it a cyclone.

“KATAMATITE

Great alarm was felt by several farmers and their families on Saturday evening when a cyclone passed through their properties. Eye-witnesses state that about 5:30 a dark cloud seemed to detach itself from the sky and with a roaring sound tore over the properties of Messrs W. Learmonth, W. Barfield, R. Gillespie and J. Colliery. The track of the cyclone was about half-a-chain wide (about ten metres) and eight miles long (about thirteen kilometres) long, and its course could be easily followed by the uprooted trees and branches of others, and posts which were standing at the butts of trees being scattered in all directions. Fortunately, there were no houses in the line of the cyclone, or they would have been demolished. Branches of trees were scattered over the road, and a party of footballers returning home from Katamatite was bogged in a table drain when the car was forced off the road in endeavouring to avoid the debris.”

My father remembered the event quite well. Coming home with his Mum after playing golf, they could see a tornado approaching them as they neared Broken Creek. Ian raced across the nearest log and, after reaching the other side, could hear his Mother yell out, “What about me? Don’t forget me!” Ian raced back over the log, picked his mother up, and carried her across the creek. Fortunately, Catherine was a petite lady.

Discussions with people who knew Catherine say she was a taciturn woman who rarely “got out and about.” However, she was a keen golfer and won several tournaments at Katamatite.

All three Learmonth children attended Katamatite Primary School. Ian obtained a Grade 8 Certificate and was awarded a Scholarship to Scotch College in Melbourne. This was to provide him with the means of achieving his goal of being a Veterinarian. Unfortunately, Ian’s family could not afford the other costs involved, so Ian remained on the farm, helping his parents.

Bill was a true Scot and loved his drink. Ian could recall many times when he and Cath sat in the ute waiting for their father to come out of the pub, usually well after closing time. His father was “game enough for anything and would swear long and loud if anything went wrong”. On at least one occasion, Bill’s lingering after closing time was brought to the attention of the local constabulary. It was reported in the February 18, 1937, edition of the Cobram Courier.

“Cobram Police Court

At Cobran Court of Petty Sessions on Monday of last week, before Mr William, P.M., John O’Meara, licensee of the Katamatite Hotel, was fined £2 on a charge of trafficking in liquor after hours and £5 on a charge of having the bar door open after hours. A charge of having persons on licensed premises after hours was withdrawn. W. Learmonth, D. McLean, T.P. O’Brien, F. Marcus, W. Watters and P. McMahon were fined £1 with ⅜ costs, with the exception of O’Brien, who appeared, and was fined £1.”

During the 1940’s Catherine developed breast cancer and had one breast removed as a result. Ian once said that he never knew if he had shown his mother the respect she deserved. Catherine was a smoker and asked Ian on several occasions to go into Katamatite to buy her some cigarettes. Ian believed that women should not smoke and refused to do as she asked. It was only after she died that his father, Bill, said that Catherine’s smoking helped her to bear the pain of the cancer.

Undoubtedly, Bill and Catherine followed the events developing in Europe during the 1930s. It would be easy to see Bill thinking about his service on the Western Front as an observer in the Royal Flying Corps/Royal Air Force and Catherine thinking of those men she nursed as a member of the Scottish territorial Red Cross Brigade. Like all families around Australia, they would have been sitting around the wireless set waiting for the Prime Minister, Robert Gordan Menzies, to give his speech to the nation at 9.15 pm on September 3, 1939. With the words, “Fellow Australians, it is my melancholy duty to inform you officially that, in consequence of the persistence of Germany in her invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war upon her, and that, as a result, Australia is also at war.” Australia would once again be expected to give up its young men and women to fight in what would end up being a truly global conflict.

Ian was only 16 when the war began. The minimum age to enlist in 1939 was 20. This would drop to 18 by 1943. Bill was 45, and although the maximum age was 40 in 1940, he still managed to enlist in the RAAF on July 12, 1941. No doubt, his experience in the RAF during the last war was taken into account. Bill remained in Australia, serving at various postings in Victoria until November 11, 1944, when his appointment was terminated due to “surplus to present personnel requirements”.

Ian enlisted in the RAAF on February 26, 1943, at No. 1 Recruitment Centre in Melbourne. He was three and a half months short of his 19th birthday. He was allocated the Service Number 430695 and the rank of Aircraftman 2. On enlistment, he was 5ft 111/4”, with fair hair, blue eyes and a fair complexion, with his trade being listed as a sheep farmer. Later that day, he was among the raw recruits posted to No. 1 Initial Training School at Somers on the Mornington Peninsula. Somers was a three-month crash course with lectures and many tests. Some topics that students were trained in include:- mathematics, navigation, law and administration, signals, medical, physical training, science, armament, gas defence, and hygiene.

After two months, a classified mustering of each member was made for wireless/air gunners, gunners, navigators, and pilots. The latter two did another month that favoured navigation. In the third month, those to be pilots or navigators were posted accordingly. All aircrew rookies had to wear a white flash in their caps to indicate their musterings until they won their wings or failed to make the grade and were sent somewhere else. Ian was chosen for aircrew - pilot.

On June 10, Ian was posted to No. 8 Elementary Flying Training School in Narrandera, NSW. Twelve elementary training schools were established in Australia to provide introductory flight instruction to new pilots. Ian’s flying logbook uses a series of numbers to identify different training sequences. On July 6, Ian had his first recorded experience in an aircraft. Flight Officer McClure took the 1st pilot’s seat in A17-609, a de Havilland DH82 Tiger Moth. Ian sat in the 2nd pilot or passenger seat. Ten days later, after ten hours of flying with an instructor, Ian taxied N9269 to the end of the runway and, after no doubt a nervous pause, took to the clear skies in central NSW for his first solo flight. It lasted a total of 15 minutes before he safely landed.

By the end of August, Ian had flown over 61 hours, slightly half of which were as the pilot. He had also spent time in the Link Trainer, a flight simulator. Having passed No. 8 EFTS, he was posted to No. 7 Service Flight Training School at Deniliquin, NSW.

Ian‘s training would include advanced flying techniques and flying the CAC (Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation) Wirraway. This aircraft was classified as a trainer and general-purpose fighter, flown by No. 9 Squadron RAAF in a ground attack support role in New Guinea. Training included formation flying, gunnery and bombing practice, cross-country navigation flights and map reading, to name a few. The course finished in mid-January of 1944. Ian had now flown over 172 hours. Whilst he attained the required standard as a pilot and a navigator, his scores for bombing and air gunnery indicated that German and Japanese pilots would be safe while Ian was flying.

On Wednesday, January 12, 1944, Ian had his final pass-out parade at Deniliquin, where he was presented with his wings and Sergeant stripes. The following Monday, he went on one week’s embarkation leave. Ian travelled home to Katamatite to spend his leave. It’s possible that he helped his mother and two sisters with work on the farm, as Bill had just been posted to the General Reconnaissance School at Cressy. Perhaps he played a round of golf or had a few hits at tennis? On January 24, he said farewell to his mother at Numurkah Railway Station. He was not to know that Catherine would pass away as a result of breast cancer only two months before he arrived back in Australia in September of 1945.

Ian arrived at the No. 1 Embarkation Depot at the Melbourne Cricket Ground at Ransford, Melbourne. He would remain there for about a week, awaiting embarkation overseas. While there, he would again be checked to ensure he was medically and dentally fit and vaccinated. On Saturday, January 29, Ian and many other service personnel walked up the gangplank and embarked on the SS Niuew Amsterdam. She was the Netherlands “ship of state”, just as the Queen Mary was for England. Built for luxurious travel for 1220 passengers before the war, her refit as a troopship would allow her to carry 6800 troops at over 20 knots. As she sailed through Port Phillip Heads at 1830 hours, Bill flew over the ship and waggled his wings, saying goodbye to Ian.

Their trip north would take them to Durban, Cape Town, Freetown, up the east coast of America, and finally, Greenock. Ian can recall getting very little sleep during the voyage, as they had to sleep in hammocks, which “you had to be drunk to get in”. Due to the fast speed at which their ship could travel, they did not always have an escort. The coming weeks saw the ship have many views, including whales, allied cruisers, and troop ships. On February 8, one man jumped overboard, and although the ship slowed down, it was too late to pick him up.

On Thursday, February 10, the ship landed in Durban on the east coast of South Africa. Personnel disembarked and were driven eight miles to Clairwood Camp, a transit camp at Clairwood racecourse. Ian wrote in his diary, “First experience with negros.” The local population were very friendly to the young Australians. They would take the Australians for drives around the area, pointing out the significant features and sites. One local, a Mrs Gee, invited the fliers for supper, tennis games and swimming at the famous beach known as Blue Lagoon. On February 16, he and a friend picked up two local girls and went to the fun park. The camp was closed on two occasions, and there was no leave. The day before embarkation, Friday the 18th, was one of those days. All South African currency had to be exchanged, most likely for English. Somehow, the “boys got drunk”.

On Saturday, Ian was back on board the ship along with other RAAF personnel, Polish servicemen, and members of the South African Army. He met up with a friend, Clive Hayes, who, along with other RAAF personnel, were put into cabins. The ship sailed at 1800 hours the following day, arriving in Capetown at 1000 hours the following Tuesday. Personnel were not allowed off the ship at Capetown, and after picking up Italian and French Prisoners of War, the ship sailed at 1800 hours.

During the last few days of February, the ship proceeded northwest. Days were filled with playing 500, chatting, and singing songs. A US Mitchell aircraft “shot” the ship up and was followed up by a Liberator. On February 28, they crossed the equator. Father Neptune caught up with those on board who were crossing the equator for the first time. Ian was amongst them and ended the day thoroughly wet.

At 0630 hours the following day, a Short Sutherland Flying boat flew overhead and shortly afterwards, two destroyers were sighted. The ship arrived at Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone on the west coast of Africa, at 1000 hours and berthed about 500 metres from the beach. Water tenders came alongside to replenish the ships’ water supply. The Italian POWs and members of the Cape Corps were disembarked. The following day was busy with oil tankers replenishing fuel supplies and RAF troops and motor launches coming alongside. The ship sailed at 1000 hours on March 2. Five corvettes escorted the Niuew Amsterdam briefly, along with Swordfish, Walrus and Catalina aircraft.

Peering over the guide rails, Ian noticed a variety of sea life: whales, swordfish and sharks. As they proceeded northwest, they passed a tanker. Late in the afternoon, a Catalina, a long-range patrol aircraft, flew overhead. Allied aircraft appeared to follow the troopship as it sailed the Atlantic. A Liberator also escorted the ship.

The following eight days saw the weather deteriorate and the temperature drop. The troops practised boat drills more frequently and were told to wear water bottles and lifebelts as they moved around the ship. The ship constantly altered course. They were getting closer to England, and there was a real threat of U-boats.

At 0900 hours on Sunday, March 12, the ship finally sighted the coast of Ireland. Spitfires shot up the boat, and Ian could see many members of the fleet, including aircraft carriers and submarines. The ship docked at Greenock, on the west coast of Scotland. Personnel disembarked at 1130 hours on the following day and entrained at 2020. Ian and his mates were still dressed in tropical kit, all of their heavy weather gear having been stored in the hold. The weather was an instant baptism into an English winter. The train travelled all that night and the following day, passing through England. Ian commented that the country was always very green with misty rain.

The train arrived at Brighton at 1530 hours on Tuesday, March 15. The RAAF personnel were taken to No. 11 (RAAF) Personnel Despatch and Reception Centre. Ian was billeted in the Metropole Hotel, one of several hotels the RAF had requisitioned. That night, Ian and a few of the boys decided to go ice skating at the S.S. Brighton. The Brighton had once been a popular theatre but had been remodelled as an ice rink during the 1930s. On Ian’s first outing in the UK, he met an East Sussex lass called Hazel.

Hazel features prominently in Ian’s diary over the next two months. They often went to the pictures, ice skating, or dancing at the Regent. It is clear from Ian’s diary entries that his and Hazel’s feelings for each other were developing into something serious. On March 17, Ian met Hazel’s father, brother and sister. Nearly four years of war had changed people's attitudes towards life. The future was put on hold. Living life fully was vital, as you never knew when it may end. On Wednesday, April 12, Ian went on leave for a week. The following day, he and Hazel bought an engagement ring and made it official. Over the next few days, they visited the towns of Hove and Lewes, which were not far from Brighton. This is surprising as preparations were being made in the south of England for the D-Day landings. Troops, armour, vehicles and supplies were building up all along the south coast. The comment was made that the only thing preventing the South from sinking was the hundreds of barrage balloons holding it up. Ian was admitted to hospital on May 6 with measles. The following two weeks in his diary are blank. He was discharged from hospital on May 16. The last reference made to Hazel was written on that same day. “Saw Hazel, cryed at our parting.”

Ian’s time spent at the No. 11 PDRC was not all social. The city of Brighton suffered frequent air raids, and Ian saw German aircraft being shot down on numerous occasions. There were lectures, parades, and duties to attend. The day following Ian’s farewell to Hazel, he was posted to No. 11 (RAAF) Personnel Reception Centre, Padgate, Lancashire. This was essentially a holding centre where Ian stayed for a few days while waiting for a posting to Whitley Bay, where they joined the Air Crew NCO (Non-commissioned Officer) School. Ian comments that on their first day, they “got hell balded out of us”. RAF Whitely Bay continued the training grounds and base for the RAF Regiment. A ground unit of the RAF that was tasked with protecting airfields. It was essentially an infantry school. Ian participated in various tasks, including weapons firing, battle manoeuvres and map reading. He was on guard duty on the night of his 20th Birthday and managed to catch 75 of the lads returning late. The RAAF airmen attending the course often showed their distaste for authority. Not agreeing with the consequences of their overstay on leave, a number of them decided to throw stones through the judge's window. Battle manoeuvres were not taken seriously, and Ian wrote that most of the boys had turned up drunk. Ian scored 81 out of 90 on the rifle range, which far exceeded his score when in the air.

Following his pass-out parade on June 20, he was posted back to Padgate before being posted to PRC Cambridge four days later. On July 22, he started at the Naval School, although his diary did not record where and what for. On July 30, he was posted to Turnhill, arriving at 1600 hours the following day. Ian continued flying through these months. At 22 EFTS (Elementary Flight Training School), Cambridge, he logged over 40 hours of flight time, primarily solo, during July, predominantly in a DH82A Tiger Moth.

On Wednesday, August 2, he left for No. 5 AFU (Advanced Flying Unit) Condover, arriving at 1030 hours. The following day, he started a fourteen-day ground school, having his first look at a Master’s aircraft. He was not to have his first flight in the aircraft until Friday, August 18. However, he was able to go solo in the aircraft after only 2¼ hours of instruction. Over the next two months, Ian’s training would include more advanced techniques, with over 80 hours of flying time. Techniques studied included camera gunnery, flying using a beacon, spinning and stalling, formation flying and day and night cross-country flying. His ability as a pilot and pilot-navigator were assessed as proficient. While attending this course, he was promoted to Flight Sergeant.

There are no further diary entries until Saturday, October 14th: “Went out with Rene for the first time and by God not the last. I’m going out with her for the rest of my life.” Irene Cowell was a Mess Steward in the WAAF. Although it is difficult to decipher from Irene’s service records which RAF base she was stationed at in October of 1944, it was likely No. 5 AFU. On the 25th of that month, he left Condover and commenced four days of leave before returning to Condover. Ian spent his leave in London and was able to be with Rene to celebrate her 21st birthday on Saturday, October 28. Ian’s diary mentions attending clubs such as the Chevrons Club in Marylebone and the Boomerang Club in Australia House near London's West End.

On Monday the 30th, he was posted to B Flight of 667 Squadron, based at Gosport on the south coast of England. RAF Gosport was principally a Royal Navy airfield during the war but was used by a mixture of Royal Air Force and Royal Navy units. Ian arrived the following day with a friend, Flight Sergeant Bruce Butchart of Adelaide, SA, at 1500 hours. At the end of October, the squadron’s aircraft strength included 19 Mk 3 Defiants, nine Mk 2C Hurricanes, three Mk 2 Barracudas, nine Mk 1 Oxford I, one Mk 2 Oxfords, one Mk 4 Vengeance and one Mk 2 Tiger Moth. Over the next few years, the squadron would increase its number of Vengeances.

On the first day of November, Ian was given 14 days' leave, and Irene got nine days leave the following day. They travelled to Rene’s home near Newcastle, where Ian met her family. November 3 saw Ian and Rene buying their engagement ring in Newcastle and publicly announcing their engagement the following day.

Returning from leave, Ian was to have his first experience in a Hurricane on Tuesday the 7th. The following week, the weather was so bad that flying had to be postponed. On Monday, December 4, Ian flew Vengeances for the first time. The month of December saw snow and weather unsuitable for flying. Ian experienced his first white Christmas. On Sunday, the 31st, Ian and Rene set off on 14 days of leave. The following week saw them preparing for their wedding. On Friday, January 5, Ian and Irene went to Newcastle to buy a wedding dress and rings. Both of them happily ate ice cream all afternoon, although Irene ended up being sick.

The wedding occurred the following day, Saturday, January 6, 1945, at St Peter’s Parish Church in West Sleekburn, a short distance from Cambois. Irene was given away by her father, Mark. According to the Blyth News and Ashington Post of Thursday the 11th of January, 1945, “the bride was attired in white figured satin, her headdress being a white net veil with orange blossom coronet. She wore a silver cross and chain.” The bridesmaids were Ruby Heraper and Irene’s sister, Betty, who wore “a blue figured lace with silver crosses, chains and becoming headdress”. Ernie Cowell, one of Irene’s brothers, was best man, and Wilfred Agnew was groomsman. Irene’s youngest sister, Doris, presented her with a silver horseshoe. The wedding breakfast took place at the Cambois Working Man’s Club and consisted of sandwiches made by the local ladies. Due to the war and shortages of materials, Irene’s wedding dress was borrowed. January 14 saw an end to their leave, and Ian and Rene returned to their respective postings, keeping in touch by telephone whenever possible.

Weather conditions improved on January 29, when Ian could return to flying. While Ian’s diary ends at the end of January 1945, his flying logbook and 667 Squadron’s Operations Book detail what he was doing. Weather conditions did not improve much until late February. During that time, with flying cancelled, Ian could obtain short leave passes, which allowed him to spend some time with Irene. Around this time, Irene managed to get a transfer to RAF Gosport, the station where Ian’s squadron was based.

With both Ian and Irene now stationed at Gosport, they decided to find a place of their own off-base. Their first home as a married couple was at 80 Priory Road, Hardaway, Gosport, Hampshire. Six months prior to Ian and Irene moving in, Priory Road had been packed with military vehicles of all shapes and sizes. The road led directly to the landing craft that was being used in the D-Day landings of June 6.

667 Squadron's function was to assist land-based anti-aircraft batteries and Royal Navy ships to practice their anti-aircraft gunnery. Other than towing a target, aircraft would also run through high and low-level bombing and dive-bombing exercises. The Operations Record Book entry for May 8 simply reads, “V.E. Day. NO FLYING CARRIED OUT”. By the end of May, Ian was only one of three Australian airmen left in a squadron strength of 136. Other nationalities included three Polish, two New Zealanders and one Canadian. During his time in the RAAF and with No. 667 Squadron RAF, Ian flew the following aircraft: DH82, Wirriway, DH84, MkII Master, Hurricane IIC and the Vultee Vengeance.

While Ian was overseas, his mother, Catherine, died on July 3, 1945, at the age of 50. One of the few things Ian mentioned was that he wished he had given his mother a better farewell, as he didn’t kiss her goodbye at the railway station. I guess many people thought it would be the service personnel who may not return.

After Germany's surrender, it was business as usual for 667 Squadron. They continued in their air-sea-land cooperation. On July 12, Ian was among eight Australian pilots posted to ACHU (Aircrew Holding Unit) RAF Cranfield pending repatriation to Australia. Ian’s last flight, besides a Link trainer, was in a Vengeance No. 504 on July 18. Ian had flown 186.35 hours in Vengeances and ten hours in Hurricanes. His total flying time in the RAAF was 106.55 hours dual and 362.30 hours pilot. He had flown 26 hours at night.

Meanwhile, on July 27, Irene had been discharged from the WAAF. On the second day of August, Ian turned full circle and was posted back to No.11 PDRC in Brighton. No doubt, Ian and Irene were frantically trying to find a passage back to Australia for Irene. She would eventually find passage on the Athlone Castle the following year. But that’s another story.

Four days later, on August 6, Ian embarked on the SS Orion. By this stage, he had been transferred to the Fleet Air Arm and, like many other pilots, was to be reskilled to join an aircraft carrier in the Pacific theatre of war. The trip home was via the Panama Canal, where he recalled, “You haven’t heard thunderstorms until you’ve heard them in the Panama Canal”. Upon arriving off the coast of New Zealand, they were informed of Japan’s surrender. The Orion docked in Melbourne in early September. He was to be discharged from the Air Force on October 23, 1945.

Some 50 years later, Ian would suffer from post-traumatic distress, waking up at night, crying, and reliving the terrible memories that haunted his past. Like many men of his era, he rarely talked about his wartime experiences, keeping all his memories and emotions hidden. It was only when he was literally on his deathbed that he mentioned some of his experiences.

Upon returning from England, Ian helped his father on the farm at Katamatite. Irene arrived in Australia on 20 April 1946 aboard the war bride ship M.V. Athlone Castle. It’s unknown how the living arrangements were at the farm at Katamatite but with the arrival of their first child, Judith Irene, on 27 April 1947, things would have gotten tighter. In November of 1947, Bill married Beryl Perry, a school teacher from Donald, which complicated living arrangements even further.

In 1949, Ian, Rene, and their first child, Judith, moved onto a dairy farm on Centre Rd, Baulkamaugh, a few kilometres west of Numurkah. He purchased the block with a low-interest loan from the RSL. Ian also attended a Wool Classing course at Dookie Agriculture College.

The blocks were parcels of farmland for which returned WW2 soldiers were eligible. The Soldier Settlement project was innovative, reflected the needs of a growing farming family, and accommodated all those who had returned from the war and needed to find a secure income.

All the returned soldiers taking up farming areas were expected to help each other build the farmhouses. The plans of the houses were all very similar. Large verandahs encircling a three-bedroom house with a huge open kitchen and dining area and a large walk-in pantry, which was the bane of the two eldest Learmonth girls' lives because it was always crammed with “stuff” and constantly in need of a good tidy up. An additional aspect was regular mice infestations when the outside climate was not conducive to mouse habitats. So they would migrate into the pantry and set up house until Ian, and it was always Ian, helped the girls find the mouse nests and get rid of them. There was no better feeling than going to bed knowing that the pantry was “mouse–free” until the next time.

The rest of the farmhouse consisted of a separate living room with a huge open fireplace and an area accessed via the living room that could be used as a bedroom. In the Learmonth family, it was needed. Ian and Irene slept in that room. The children slept in the bedrooms. There was an anomaly about the size of your house. If the family had many children, they were entitled to what was euphemistically called the sleepout. The builders would erect this one-roomed, freestanding building that was supposed to be used as an extra bedroom. However, the older children have yet to recollect this room ever being used as a bedroom. They took it over as a playroom and spent hours building tents in a rather messy room. There was only one small bathroom for all these family members and an outside toilet, which meant they had to go outside, under the rose trellis and past the vast mint garden to go to the toilet. It was horrible as it always smelled weird, and with five children and two adults, it was in constant use. Irene was always calling out to Ian,

”Ian. The toilet needs to be emptied.

Ian. The toilet is full.

Ian. The toilet is overflowing.

This was before the installation of a septic tank, and the toilet can had to be taken away and emptied into a pit, and the waste was buried. Poor Ian. What a ghastly job! He was always busy with the animals, the land, and the twice-day milking of the cows. Added to the drama of “going to the smelly toilet” was the fear of spiders, snakes and various other wildlife hanging around the open door. Soft, white toilet paper was a thing of the future. Toilet paper consisted of old newspapers carefully cut into squares by the girls. Nobody wanted to go to the toilet after dark. If they just HAD to go, they always took someone with them as frontman and guard. There was no enticement to bring a book to the toilet (a hereditary trait in the Learmonth family) and have a quiet read.

They had a laundry, but initially, there was no running hot water. So, every washing day, Irene had to light the copper. This was a big round copper tub with a fireplace underneath. Before beginning the washing, the fire had to be lit so that the water in the copper could be heated. Washing took all day. There was a simple washing machine with a wringer that had to be turned by hand. The huge sheets, shirts, work trousers, everything had to be taken from the machine, squeezed by hand to get rid of excess water and then hand fed through the wringer with one hand whilst the wringer handle was turned by your other hand. Irene must have developed strong muscles.

Before the farmhouse was finished, the family lived in the tin garage that was part of the home paddock. It was primitive, with just two rooms; one area was for living, eating, and sleeping, and a small area at the end of the big room was for the kitchen, with a wood-fired stove and possibly a dirt floor. It would be interesting to know how Irene reacted when she saw the conditions she was expected to endure. Fortunately, there was only one child at this time, Judy. Still, it would have been a great cultural shock for a young, blond, fair-skinned bride from England.

An early Christmas present arrived for the small family. On December 20 1949, Christine Vivienne Learmonth was born at the Cobram Hospital.

The family eventually moved into the farmhouse, which must have been considered luxurious after the tin shed. After everyone was in bed, Irene and Judy would sit on chairs in the kitchen in the farmhouse, in front of the big slow-burning stove, drinking Milo with their feet in the warm oven.

As Judy was the eldest of the children (and in the absence of a suitably aged son), it fell to her to be the cowhand. She never questioned this. It was just the way it was. Equality was never a question. Everyone was expected to help. Work ethic is developed through example and expectation.

Judy never had to help with the morning milking. However, after returning from Numurkah Primary School on the bus, she would change into her beautifully ironed pinkish denim jeans and neat top. She would put on my gum boots and trudge over to the diary to help with the milking. As each sibling grew older, they helped with the farm jobs. Judy has vivid memories of her time in the diary. There is a particular smell that brings it all back to her. She only has to drive through a diary area in any part of the country, and she is transported back to helping her father in the diary. It was the smell of cow manure, damp soil, and the aroma of the milk as it came from the cows, which were stored in the milk cans and at a later stage in the milk vat.

The farmland stretched into two areas. In the middle was a large irrigation channel with a bridge over the channel and a spillway where the children loved playing Pooh Sticks. Ian would scare the daylights out of them by driving the tractor down the steep banks of the channel with them on either side of him, screaming and hanging on for dear life. A long lane went from the farmhouse and dairy, over the bridge and down to the back paddocks.

The diary would be considered primitive compared to the vast systems of today. There were possibly six milking units. It was one the girls’ weekend jobs to bring the cows up from whatever paddock they were eating in at that time. She recalls walking behind a mob of cows and skipping around the mounds of cowpats that seemed prolific when heading to the dairy. The cows needed no enticement to get to the dairy as their udders were full, so they would have been desperate to be milked. This was Ian's daily pattern: twice a day, seven days a week.

The cows had to be brought from the holding yard into the bales. They were held in the bails by a neck yoke, and if the animal was a little stroppy, it had to have a rope tied around one leg to stop it from kicking out when the milking cups were applied to the teats by Ian. Initially, the milk went through the system to milk cans. One of Judy’s jobs was to ensure that when the can was full of milk, she had to let Ian know, and the can was replaced with an empty one. No precious milk was to be lost. The cans were put out to be collected. They were placed on the trailer behind the tractor and taken to the farm gate, where a truck collected them and delivered them to the milk factory. Eventually, the diary was updated, and a huge milk vat was installed, making the system more user-friendly. Now, the milk tanker would drive to the dairy and connect a pipe to the vat. There was a circular driveway where the milk tanker entered the property. Judy recalls how she “saved” Dennis’ life one day. He was riding his bike around the circular drive and fell into the deep, water-filled rut the truck had created around the inner part of the drive. His foot was stuck in the pedal, and he could not escape the water. Things could have been nasty if she hadn’t held his head and shrieked for help.

If Ian was alone in the dairy and needed something, he would stand at the entrance and emit this piercing whistle that could be heard back at the house. One of the kids would be sent scurrying over to the diary to find out what he wanted. Ian often squirted fresh milk straight from the cow’s udder into the children’s mouths. The warmth, the smell and the taste of that milk were amazing.

The children would often have a friend come and stay the night. Judy remembers having a friend, Beverly, over to stay. She lived in Numurkah. She came over to the dairy with her. When the cows came into heat, they would jump on the rear end of another cow and roar around the holding yard. As a child living on a farm, she assumed this happened when the cows were ready to be taken to the bull. It didn’t mean anything to her; it was just what happened. However, when her “city “ friend Beverly saw this, she turned a brilliant red and ran out of the dairy and back to the house. Ian and Judy just shrugged their shoulders and moved the next cow into the bales.

April of 1952 saw the Learmonth family increase by a third as twin girls, Patricia Margaret and Pauline Allison were born at the Numurkah Hospital on the 13th of that month. Two years later, on October 31, 1954, a son, Ian Dennis was born at the Numurkah Hospital.

Every animal on the farm had a name. They had pigs, cows, bulls, chickens, horses, dogs and too many cats to count. One of their famous cows was named Marj. She was a brindle colour with a slow, meandering gait. Her personality could be described as “grumpy”. She gradually deteriorated over time and developed a wheezy kind of laboured breathing. She continued to, reluctantly and with great disdain, meander up to the dairy to be milked. Ian would mutter now and then, “Marj is at the end of her productive life.” The inference was that she would be sent to the market and because of her age, that probably meant she would be taken to the yards to be killed for pet meat or something as unimaginable as that. The children knew that periodically, animals would be collected by the cattle transport. Although they never thought about what they were heading towards. Despite this, Ian only had to mention Marj and her future, and great wailing and drama would follow from the family. However, the inevitable happened when Marj developed a severe limp. She did disappear. Not sure how or when. But one day, she just wasn’t there anymore.

Another activity that gave the children a lot of grief was the killing of newborn calves. Some still have flashbacks about this. Female calves were valuable. But at the time, male calves were not worth raising or sending to market. Ian’s solution, probably the usual practice, was to ‘hit them on the head”. The bodies were not always buried. It was their worst horror to be trudging across a paddock and come upon the rotting carcass of a newborn calf. For farmers, it was just a way of life, as every animal had to add to the value of the farm's output.

There always was entertainment living on the farm. The Baulkamaugh Tennis Club was very active, and Ian and Irene were part of the team. Every Saturday in Summer, the family would be packed into the car and driven a few kilometres to the tennis courts and clubrooms. As soon as they arrived, the children would all be off, running through the trees, meeting up with mates, building cubbies and fighting with their enemies. They would not be seen until a whistle from Ian brought them back to the car to make it home in time to do the evening milking. They loved it. As time passed, some of them took up playing tennis. However, they all spent hours at home with an old tennis racket and a dog-chewed tennis ball hitting against the shed wall.

Card evenings were huge on the agenda. The games occurred at homes such as the Boases, Orams, and Nishes. No babysitters were needed as they all went out for the night. After these evenings, Ian often carried the children into bed. District families would often have euka nights at the Baulkamaugh Hall. This practice would continue when the family moved into Numurkah. Smoking was viewed as a social norm, with many people having taken it up during their service years. The Learmonth kitchen would resemble a London peasouper with smoke so thick you had to cut it to see anyone.

Dance evenings were also a major social event for the community. The family always arrived at the hall early enough to find a car park near the hall entrance. When Ian and Irene went into the dance, the children would be bundled up in the car with pillows and blankets and expected to sleep. Intermittently, they would come out to check on us. The Learmonths always had small cars. So, with all the children trying to sleep in the front and back seats, it was uncomfortable. At various times, the family owned a ‘beryl green” Volkswagen, a burgundy Skoda and a two-toned (green and white) Holden sedan.

The kitchen was the hub of the family's lives. They played card and board games, did jigsaw puzzles, listened to radio serials such as Dad and Dave, and slept on the couch when unwell.

The Learmonths were one of the first families in the district to own a television. This came about as a payoff when Irene and Ian went on holidays to Horsham and left the children with their ‘Aunty’ Mavis, Christine and the twins' Godmother. On many weekends, the family would find neighbours and friends in their lounge room, watching television. Even Irene’s hairdresser would come out from Numurkah just to watch television.

After spending some time in poor health, Ian was hospitalised at Mooroopna with hydatids. Over the next three years, he spent some time in hospital. Finally, he was operated on by the late Weary Dunlop, a famous Australian surgeon who, while being a prisoner of war of the Japanese, operated on many fellow prisoners. Weary refused to charge any fees to ex-servicemen, a practice that got him into trouble with the hospital. During that time, Irene and Christine, who was eight then, would do the morning milking, while Judy was responsible for running the household, which included looking after the twins and Dennis. Irene would visit Ian regularly, sometimes travelling by train from Numurkah, whilst on other occasions, a family friend, Jack Whitfield. Family friends would also help the family in many ways, such as farm work, food, and household chores.

Ian’s poor health meant he could not carry on with the farm. So everything was to be sold. These were great social occasions in the district, and everyone would come from all the surrounding districts to find a bargain (animals, farm machinery, furniture, household items we no longer needed). It was probably a bit like an enormous garage sale. The children stayed home from school as it was an important date in their history. Judy and Christine climbed to the top of the farm's windmill, the tallest structure, and sat on the small, narrow platform surrounding the tank. They spent the day there hiding away from the crowd, but also able to view all the action on the ground below.

Ian, Irene, and their family moved to Numurkah in 1961, purchasing a house at 6 Patterson St. The Numurkah Leader of February 21, 1961, included an article about Ian taking up the Caretaker’s position at the Numurkah Town Hall. Of the original thirteen applicants, three were selected for the interview stage. Before the appointment, the Shire Secretary, Mr J. Reed, said the council was sticking rigidly to the Discharged Servicemen’s Preference Act, which stated that all things being equal, ex-servicemen must be appointed to positions to which they apply, providing they have the necessary qualifications. Ian was the only ex-serviceman to apply. Ian’s starting salary was £1170 a year. Ian would retain the position for 23 years until his retirement on July 13, 1984.

One day, the family expanded with the acquisition of a black Scottish terrier, Jedda. She was beautiful and gave the family great joy. She would be the first of many dogs, cats, budgies and canaries.

He also drove school buses for Wannenmachers and then Caldwells of Numurkah, retiring from this position on the same day as his retirement from the Numurkah Shire. In 1984, Ian was awarded the Numurkah Rotary Club’s Vocational Services Award.

Many ex-servicemen and women lived in the Numurkah district. It had an active RSL, and Ian and Irene would often enjoy a game of billiards or indoor bowls at the clubrooms. The year's highlight was ANZAC Day, when people would raid their gardens for flowers of all different shapes, sizes and scents. The RSL ladies would then create a large floral tribute to those who had served. The front of the Numurkah Hall stage would become a floral masterpiece, and the room would be filled with the appealing scent of freshly cut flowers.

By the 1970s, Ian’s father, Bill (or Scotty as he was well known) and stepmother, Beryl, were living in Geelong. Bill and Beryl had come home for Christmas of 1975 and were catching up with some family friends. Ian, Irene and some of their children were playing.

Canasta, a family favourite, to help see in the New Year. There was a knock at the door, and Ian went to answer it. It was the local police, informing Ian that Bill and Beryl had been killed in a car accident, not far from where their old farm was at Katamatite.

Family holidays tended to be spent at one of the siblings' homes after they married and moved away. Irene, Ian and Stephen saw a lot of Victoria. Often, it would be just Irene and Stephen as Ian stayed home and worked.

In 1984, Ian was awarded the Numurkah Rotary Club’s Vocational Services Award.

In 1985, Ian and Irene sold the family home in Numurkah and moved to Bendigo to be closer to some of their children. They spent some time in a unit their youngest child, Stephen, had just vacated. Irene continued to grow frail. On October 10, she was rushed to the hospital due to massive bleeding. She was immediately taken into the operating theatre, but died due to cardiogenic shock due to the significant loss of blood. She was buried on October 14 in the Numurkah Lawn Cemetery.

After Irene died in 1987, Ian moved to Shepparton to be closer to friends and family. In 1990, he met Maisy Opi and moved in with her sometime later. They were both to provide each other the companionship and friendship they needed.

In 2000, Ian became quite ill and eventually moved into a Nursing home. Early in 2001, he became very sick and was admitted to Goulburn Valley Base Hospital in Shepparton. He died on February 14, 2001, and was buried at the Numurkah Lawn Cemetery, next to Irene, on February 19, 2001.

Ian was a very quiet man who was a product of his father. In that, his ability to talk through issues or even show his love reflected how he had seen his father demonstrate his feelings. He was a very early riser, probably due to the many years of milking cows, leaving for work well before the family got out of bed, and would often go to bed early. He was always willing to go that extra mile for other people to ensure the town hall was open and clean. Memories are not just about what we see but often what we hear or smell. He was an excellent whistler, and fond memories are of hearing him whistle out some tune while he was sweeping or washing floors. The acoustics of the Numurkah Town Hall were such that the sound reverberated into every room and out the main door. It was such a delight to hear.