GREENFIELD, Joshua

| Service Number: | WX3546 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | 28 May 1940 |

| Last Rank: | Corporal |

| Last Unit: | 2nd/16th Infantry Battalion |

| Born: | PALESTINE, ASIA, 21 August 1918 |

| Home Town: | Not yet discovered |

| Schooling: | Not yet discovered |

| Occupation: | Not yet discovered |

| Memorials: |

World War 2 Service

| 28 May 1940: | Enlisted Australian Military Forces (WW2) , Corporal, WX3546, 2nd/16th Infantry Battalion | |

|---|---|---|

| 29 Nov 1945: | Discharged Australian Military Forces (WW2) , Corporal, WX3546, 2nd/16th Infantry Battalion |

From the memoirs of Josh Greenfield

Joshua Greenfield was born in Safad, Israel on 19th August 1919. His father came to Australia in 1938 to make a better life for his family. He opened a fruit shop in Perth, where he had relatives, and Joshua followed in 1939 to help his father. The year 1939 was meant to be the start of a new life for his family but became much more significant. Tragic news was coming through from Germany regarding the activities of a man called Hitler and what he was doing to our people. Why doesn’t somebody stop him? What is the civilized world doing about it?

We did not have to wait long for the answer to these questions. The picture was so clear in my mind. It was the 1st September. My father and I were standing outside our shop early Sunday evening.. We heard on the radio that Australia declared war on Germany. I knew there and then what I must do.

My father read my thoughts. He did not raise objections. I knew I was reading his thoughts too. If he was a young man he would do the same.

The following morning after completing my pickup and delivery, I rode to the nearest army barracks at Karrakatta which was halfway between Cottesloe and Subiaco. I had ridden past these barracks many times without giving them much thought, but this time I went there with a purpose. To offer my services to fight Hitler’s Germany.

I took my identification papers together with my discharge papers from the Palestine Police. The officer who interviewed me was quite impressed with my credentials. Unfortunately his next question put a temporary halt to my military ambition. He asked me if I was a naturalized Australian. The answer was “No” because to be naturalized I would have had to be in Australia for a number of years. The officer was as much disappointed as I was. I remember him saying to me he would have liked very much to have me serve in his company, but the law said that you had to be born in Australia or naturalized to be able to volunteer for military service overseas in the Australian Imperial Force (A.I.F.).

The ride back to the shop took much longer. I felt very much let down. When I told my father the bad news, I cannot remember whether he shared the same feelings with me or was rather relieved. I carried on my job in the shop as best I could, all the time listening to the radio and reading the newspapers about the havoc and destruction Hitler was causing to innocent people in Europe. We were waiting for the big counter offensive that Britain and France were going to mount on Germany. It will all be over very soon. Hitler will have no chance once the British and French armies set off after him. These were the general opinions of my lady customers when I picked up and delivered their orders. The more I listened to them the more I was being convinced that neither I nor the Australian Army will be needed to defeat Hitler.

Once again that was not to be. Two months later Hitler was still marching on. Notices appeared everywhere stating that all male Australians who had turned twenty-one must register for compulsory three months military training. The word naturalized did not appear on the notice boards and twenty was near enough to twenty-one, so I registered. After passing the medical examination, I was informed to report to Perth railway station at 0900 hours to board a train which would take me to Northam Military Camp for three months. It was still a long way from going overseas but nevertheless it was a start.

The train journey to Northam was not long, about one hour. I shared a compartment with seven other young men. I felt very lonely. I could not engage in conversation, the language barrier was very obvious. The men were courteous enough but I was glad when the train reached Northam and I could get out. The camp was a short walk away and by the time we got there I started to feel more relaxed. We were together for one purpose and comradeship soon started to develop.

After the issuing of uniforms, we learned how to make our own mattresses. Plenty of straw and a large chaff bag were to be our bed for the next three months.

I was adapting to the new life style quickly and it was not long before I could express myself more freely. We shared large huts and they had to be kept tidy all day. There was a daily inspection, which reminded me of my Kadoorie days only the beds at Kadoorie were much softer and the punishment for untidiness was less severe.

Then there was the handling of the rifle and rifle drills. My Sergeant Major was quite surprised to see how well I was managing these exercises. I forgot to tell him that twelve months in the Palestine Police had a lot to do with it.

A few days later we had our first lesson in handling the Vickers machine gun, the same machine gun that the British Army used in 1929 outside our house in Safad. How thankful I was for the lessons I was given way back then. That’s where my mind was when the sergeant thought I was being rude and not listening to him. He turned to me and said, “I suppose you know all about this”? I did not realise he was being sarcastic and I answered, “Yes”. “OK come over and show us” was his next command. So I did. And you should have seen his mouth wide open and so were the rest of the squad. I did not realise that another person was watching, an officer riding a horse supervising the training squads in the area. After the lesson he called me over and said, “I know you. You were in the Palestine Police. You came to see me to enlist in the army”. I did not recognise him and he did not mention the word naturalized. My Sergeant and the Sergeant Major were no longer surprised and soon after, I was to be known as Corporal Greenfield.

The training was of a high standard and they drilled much into us. We did plenty of mock battles and plenty of long route marches. I made a few good friends. On our long weekend leave, they invited me to their homes for dinner.

At the conclusion of the three months training, the war in Europe was escalating. The first Australian Army division, the 6th, was ready to leave for overseas service and the second division, the 7th, was being formed. They asked for volunteers and I did not have to be asked twice. Here was my opportunity to pass the naturalization requirement. The 2/16 Battalion was the Western Australian part of the 7th Division and by May 1940 I was in the machine gun platoon of the 2/16 Battalion.

I had a month’s break between the three months training and joining the 2/16 Battalion. I spent the time with my father in the shop. He appreciated the time and help I gave him in the business. He already had a young boy doing the deliveries so any help I gave him was in the servicing and gave him the occasional time off to go to the pictures or visit his nephews.

A month is not very long and the time came for me to return to Northam Camp and prepare for overseas service. As new batches of recruits arrived at camp, the existing soldiers met them at the entrance gate with the traditional welcome of “You’ll be sorry”. These words were getting louder with every new arrival. One day a batch of volunteers from the gold mining town of Kalgoorlie arrived and I was amongst the welcoming committee shouting, “You’ll be sorry”. I then spotted a very familiar face. An old friend from my school days, Johnny. (Johnny came to Australia a few months before me. He was working for my father in the shop before I came and helped me learn the Australian ways. After a falling out with my father he left the shop). You could have knocked me over with a feather! All was forgiven and we were so glad to be with each other again. As the war was hotting up they became more lax in recruiting requirements and Johnny had no difficulty in joining up even though he was not naturalized. But fancy, for all the army branches he could have joined, it had to be the 2/16 Battalion. We had no difficulty in arranging for both of us to be in the same platoon, which was the machine gun platoon. I promised not to pull rank on him, seeing that I was a Corporal.

When I joined the Australian Army in 1940, the Church Parade on Sunday mornings was compulsory. It was conducted separately by each Company. They then marched to their respective services.

On our first Sunday Church Parade, Johnny and I, the only Jews at that time in our Company, assembled with the rest of the troops. After the roll call the order was given. “R.C.’s fall out” and all the Roman Catholics stepped forward and marched off to their service place. The next order was “Jews fall out” and Johnny and I stepped forward and were ordered to report immediately for kitchen duties. The remainder of the men being “Church of England” marched off to their service.

While Johnny and I were sitting in the kitchen peeling potatoes and not particularly enjoying it, we looked across to the football ground and noticed the church goers were already kicking the football. The thought that this could be repeated every Sunday did not impress us. It certainly called for fast thinking.

The next Sunday we again lined up for the Church Parade and after the R.C’s were marched off the order “Jews fall out” was given. Johnny and I stood still, looking ahead. The officer must have thought we did not hear him so he repeated the order. Still no Jews stepped out. He gave up and we all marched off to the Church of England service.

That service appeared to be a lengthy one because when I looked across to the football ground I noticed that the R.C’s were already kicking the football. Johnny looked at me and I could read his thoughts. Why not R.C next time?

The following Sunday when the Officer called out “R.C’s fall out”, Johnny and I also stepped forward. The officer gave us a sharp look but it made no difference. We both stayed put and marched off with the other Catholics. The service was held in a large hut and it must have been a Catholic “Yom Kippur”. I lost count how many times I was down on my knees. It looked like the service was never going to end. I could hear the football being kicked around by the other mob and we were still on our knees.

How are we going to win this battle? Surely there must be another way. We did not want to go back to peeling potatoes.

We made a direct approach to the Army Chaplain and explained to him the dilemma we found ourselves in. He was very sympathetic and was surprised that such a situation existed. He asked us to leave the matter in his hands.

The following Sunday was the usual Church Parade with the usual roll call. The R.C’s fell out and marched off, then came the order “Jews fall out”. Johnny and I stepped forward and to our great relief the next order was “Dismiss”. As we marched off I could hear one of our friends say, “Next time there is a war on, I’m going to join up as a Jew”.

The training was being intensified. We spent a lot of time target practising with rifles and machine guns. We also underwent many three day route marches, sleeping under open skies. Once or twice we did a twenty-four hour march. March for fifty minutes, rest for ten, twice around the clock with only six hours sleep. This was certainly no life for the weakling. I could not help thinking what my doctor at the Hadassah Hospital in Safad, where I spent three months, would have thought if he could see me now.

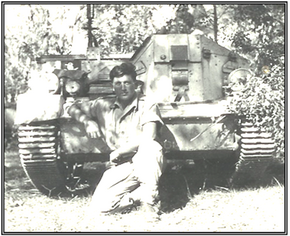

The Army introduced machine gun carriers. They were miniature open tanks run on tracks, but fairly fast and manoeuvrable. The idea was to be able to move machine guns quickly and give support where needed. There were nine carriers attached to our battalion, each one was in the charge of a Corporal. Three made up a section under the charge of a Sergeant and nine made up the total platoon which was under the command of an officer. Each carrier had three people in it; the Corporal, the driver and the machine gunner. The Corporal was sitting in front next to the driver. My carrier was being referred to as the foreign legion carrier with me being from Palestine, the driver was a Scotsman, and the machine gunner was an Irishman. We did not understand each other very well, but somehow we managed to get by. Johnny was in another carrier.

The time had come for our battalion to join the other units of the 7th division to go overseas for active service. As a farewell gesture, our battalion marched through the streets of Perth. “A thousand men marching to war”. The streets were packed with well wishers. We were showered with flowers and confetti and many kisses. It certainly was a day to remember. We broke up in the gardens near the Swan River. A large crowd of friends and relatives joined us. My cousins Hope and Anne were there, together with a few other friends and we spent two pleasant hours before it was time for us to return to camp We were given embarkation leave, to have a few days with our families before leaving Australian shores. My father and I spent a few sad moments. We both realized that it may be a long time before we see each other again, if ever.

I managed to catch up with some of my mother’s letters. They were sad letters covered with many tears. In one of her letters to my father she wrote, “What have I done? I managed to get him away from being a Gaffir and now he becomes a soldier and going to war. I cannot win”. I replied, “Dear Mother, that makes two of us”

The day has come. A convoy of ships were being assembled off the coast of Fremantle. The eastern state troops of the 7th Division were there waiting for the Western Australian units to join them and to be escorted by a war ship to some faraway place.

We boarded the train at Northam for an express run to the Port of Fremantle. The train was packed with troops and their battle gear. All along the way the train’s whistle did not stop blowing and people everywhere were waving goodbye. I made a small flag using a white handkerchief and wrote a goodbye message to my father. As the train sped through Cottesloe station, I threw it on the platform hoping he would get it. I could not see him but some kind person took the message to him.

There were three troop carrying ships in our convoy plus one escort war ship. Our ship, the Aquitania, was huge in comparison to the Larges’ Bay. The other ship was the Queen Mary. The third ship’s name I cannot recall but she was not as big.

It took me a few days to find my way around the Aquitania. We spent much of our spare time on deck. Once or twice we had boat evacuation drills. Each soldier had to report to his commander at a fixed spot on deck wearing his life jacket ready to take to the life boats. We were always prepared for an emergency. It was compulsory for each soldier to always carry his life jacket no matter where he went. The ships kept well apart from each other and were always zigzagging so that they would not be a stationary target to enemy submarines should they be there.

Our destination was top secret. The betting amongst us was England. The sailing was smooth and our accommodation, well, could have been worse. We were issued with hammocks and we slung them where we could, mainly on deck, weather permitting.

At night, light restrictions were in full force. No lighting or smoking of cigarettes on deck. Heavy curtains were used to block doors and port holes. During the day between our meals and relaxation we had to perform many exercises to keep the body in good shape.

One night while I was enjoying a good night’s sleep on the top deck, I woke to hear a big commotion around me. “Man overboard. Everybody report to their stations”. This was the order coming through the ship’s loud speakers. Men were running everywhere. I got up as quickly as I could and raced to my station. The ship’s lights were on and the escorting war ship was circling our ship, with her search lights on full beam. I could not help thinking, all this in the middle of the night where lighting a cigarette would have got you in severe punishment, now the sea was full of lights to save one man’s life. That’s what makes Australia so different. Three thousand men reported to their stations and the roll calls were taken. My section could not account for one man. His name was Bluey and he also happened to be a good friend of mine. I felt terrible thinking of poor Bluey floating in the big ocean, probably taken by a shark. With him reported missing and the search lights not revealing anything, they called the rescue attempt off and all the lights went off. With difficulty I made my way back to my hammock. Feeling my way in the dark, as did many others, I suddenly stumbled over something. I felt it and it was a body. I shook it and Bluey sits up and wants an explanation as to why I woke him. The conclusion was that a sand bag fell overboard and somebody mistook it for a body and gave the alarm “Man Overboard”.

The convoy proceeded without any further episodes till we reached Bombay, the main port of India. There we disembarked and were given shore leave till midnight. Before we left Perth, Johnny and I met friends who had relatives living in Bombay. They asked us to look them up if we went there and gave us their address.

We were at the city centre square and decided to pay our friend’s relatives a visit. We hailed a taxi and showed him the address. He said, “OK, hop in”, and an hour later he pulled up and said, “Here it is”. We got out and paid him handsomely, even gave him a bit extra as a tip because he went so far out of his way. He thanked us and drove off. We walked up to the front door of the address given to us, rang the bell and there was no answer. After a few more attempts and rechecking the address we decided it was a waste of time. We regretted not asking the taxi driver to wait because it was a rather quiet street and obviously a long way from the city proper. We asked one of the locals where we could get a taxi. He told us if we walked down to the corner and turned left we would have no trouble getting a taxi. “Only a few minutes” he said and he was right. A three minute walk and we were back where we got the taxi in the first place. How we would have liked to get our hands on that taxi driver.

We had a few drinks then decided to have a look around. An Indian man kept asking me to have my fortune revealed. I could not chase him off so I let him have a go. He told me many things that I don’t remember, but one stuck in my mind. He said, “You will be going home soon”. To me home at that time meant Australia, and the only way I could get back to Australia was if I should get badly wounded and that was something I did not particularly like to hear. I paid him his “Rupee” and told him to buzz off. It was two weeks later I realised what he was trying to tell me.

The next day we were on a slow train for a journey inland to a British Army camp. The train journey turned out to be longer that we expected. It was late at night by the time we were shown to our sleeping quarters. One large hut with bunks on each side and it did not take us long to be in dream land.

I was awoken by a smiling Indian boy saying, “Time for a shave, sir”. All around me soldiers were sitting up in their bunks and having their faces shaved. What’s more another Indian boy was polishing my boots. What a life! How long has this been going on? By the looks of things the British have been having this for the last four hundred years.

We obviously paid them too much for this service. By noon there was a large notice posted by the British High Command that under no circumstances shall we pay more than two pennies for a shave and a similar amount for polishing our boots. So much for British control of their subjects.

All good things must come to an end and soon we were packing for our onward journey. Another convoy was waiting for us at Bombay Harbour. This time smaller ships were to take us to our destination, but where will that be?

Two days out to sea we were ordered to assemble on top deck and the commanding officer told us that we were going to Palestine. So that is what the Indian fortune teller was trying to tell me.

How the wheels of fortune were turning. It was one year and nine months since I left the shores of Palestine. Didn’t I promise to be back in twelve months? Not very far out, but who would have thought that I would be back under these circumstances.

We were given instructions about the local inhabitants, Arabs and Jews, but mainly about the Arabs because we were to camp in the south of Palestine which was highly populated with Arabs. My friends who knew my back ground came to me with questions. They thought they might as well get information direct from the horse’s mouth.

I was getting very emotional. My thoughts were that soon I would see my family and friends and they would see me in the uniform of an Australian soldier. The older population of Palestine well remembered the Australian soldiers in the First World War. The Light Horse Brigade left a great impression and was greatly respected.

There were no specific incidents on board as the convoy made its way up the Suez Canal. It gave me another chance to have a good look at the canal and appreciate its magnitude. It was nice standing on the deck and seeing land so close to each side. Going to Australia I hardly saw the canal because we boarded the Larges’ Bay towards evening and I was too busy finding my way on the ship rather than taking in the scenery. Now I have plenty of time to look around and return the occasional wave from along the banks.

It was not long before the ship was tied up at Port Said. This time there was no shore leave and we were soon loading up on a train to take us to Palestine. It was a long journey and the train was not fit enough for cattle, which is why I could not see any. There were only men and equipment and not a spare foot to lie down. Somehow we managed and at long last we reached our destination, Julis Camp.

The first thing we had to do was to erect our tents and we were issued with stretchers so we could catch up on some lost sleep. We were also given a word of warning that the Arabs are known to sneak into the tents at night and pinch the rifles. We were taught from the beginning that the rifle is the soldier’s best friend and nobody wanted to lose his best friend so we chained the rifles to the centre pole of the tent during the night.

The next exciting moment was the mail delivery. We had been away for a full month and this was the first opportunity for the mail from Australia to catch up with us and what a pleasant surprise. I had over twenty letters. It took a bit of catching up. If only the Sergeant Major would leave us alone for a while. Perhaps nobody loved the Sergeant Major and he did not have too many letters himself.

That night I was glad to go to bed. What a hectic day it was. I still felt shaken up by that long rattling train journey. I don’t think it had dawned on me yet that I was back in Palestine. The sound of the bugle in the morning as always came on too early. How we all hated that sound. Why couldn’t the bugler sleep in?

After the morning run we cleaned up and had breakfast. It was then that I had my first encounter with what I called home. Our tent was not far from the main road and I noticed a road gang working beside the road. One of them looked too good to be a bloke. I was not the only one aroused by the curiosity. As a matter of fact the whole company were converging on the gang. I got there first and my opening salvo of “Shalom, ma-shelomchem” reversed the curiosity. How can an Australian soldier, after being here less than twenty-four hours speak so good Hebrew? How my friends envied me. It appeared that a Jewish kibbutz was situated not far from our camp and their members were doing odd jobs in the district. This was common in those days especially with new Kibbutzim trying to build up their own farms. Johnny and I certainly felt that we were back home.

With all the foreign armies converging on Palestine the Jews vs Arabs struggle was put on temporary halt. A great number of the Hagana were joining a Jewish regiment to serve with the British Army later on in Europe. The Arabs on the other hand were adopting to wait and see.

I was looking forward to seeing my mother in Safad. Unfortunately Safad was a long way from Julis camp and the only leave pass we could get was a daily one which took us to Tel-Aviv. It was a nice break but I didn’t know anybody in Tel-Aviv. Julis was too far for my mother to travel but my sister Rachel could not wait much longer. She managed to persuade Uncle Usher to take her to Julis. With her looks and charm, Uncle Usher had no alternative. I remember the day so clearly. It was a beautiful day and the thoughts that I will be seeing Rachel soon made the day more beautiful. I waited near the main road and saw the taxi pull up one hundred yards short. Rachel got out, spotted me from that distance and made the fastest sprint I’d seen in a long time. I made her sprint a little shorter as I raced towards her. There we stood embracing each other in the middle of the army camp. We ignored the whistling. I did not bother telling the men that this beautiful young lady was my sister.

We spent a couple of hours together catching up on the last eighteen months. I could not get over how much she matured since I last saw her. I thanked Uncle Usher for coming and bringing Rachel. Then it was time for them to depart. They had a long way ahead of them back to Safad.

I applied for a few days leave but as yet it was not forthcoming. There were lots of preparations the Army was undergoing and it kept us fairly well occupied.

My brother Moshe paid me a visit. He was now working in Jerusalem, having been transferred from Haifa. I was indeed very happy to see him and catch up on old times. Jerusalem was not far from Julis Camp and he promised to visit more frequently.

At last my special leave pass came through. Boy was I getting excited to see Safad again, my dear mother and all my friends. I had to change buses a few times on my way, the last one being at Haifa which took me the rest of the way. As the bus wound its way up the mountain taking sharp bends, suddenly a most picturesque sight appeared in the distance. Safad. How my heart lost a beat. To me it was the most beautiful sight in the whole of Palestine.

From there I was on very familiar grounds. The next stop was Meiron. How many nights we spent there on Lag-B’omer and climbing the Hatzmahon, the tallest mountain in Palestine, one thousand two hundred meters. Many pleasant memories were flashing back in my mind especially that magnificent view of the sunrise from the peak of that beautiful mountain.

After the brief stop at Meiron the bus proceeded towards Safad and not much further were the sights of the remnants of shattered dreams. Yes, there in front of my eyes were the burnt out empty buildings of Ain-Zeitim. Within one minute the bus would leave this tiny spot behind me but how could I brush aside so many years of toil and suffering. Not once but twice in such a short period of time. The years 1929 and 1936 were flashing back in my mind and there on top of that hill amongst the ashes laid buried that beautiful dream, Gal-Ed. I shed a few tears. The Arab woman sitting next to me on the bus must have wondered why. A few more bends in the road and the bus was coming to a grinding halt. I was back in Safad.

There was no national holiday as far as I knew, so I was amazed to see so many faces at the bust stop. Of course amongst those faces was my dear little mother. Being short she could easily get lost in a crowd, but no crowd could keep us apart. Her dear Joshua had returned. We embraced each other, tears streaming down her face. Was she really glad to see me in the uniform of an Australian soldier?

We were walking home from the bust stop but not alone. There must have been dozens of friends and neighbours walking home with us. What have they done with the streets? They had shrunk and everything looks so tiny. What the big world has done to tiny Safad. However, I still remember a very old saying. Sweet things come in small packages. How true that was about Safad.

I could not get over how mature my baby sister Ayala had become. They certainly grow up fast. My holiday was proving to be most enjoyable. I remember my first night home. My mother prepared the best bed in the house, using a beautiful soft feathered mattress. How disappointed she must have felt in the morning when she found the mattress and me on the floor, which goes to show that you cannot mix comfort with Army life.

Holidays don’t last long and seven days went by very quickly and it was time again to say good-bye and hope to see them all soon. It’s always sadder going than coming and the trip back to Julis was rather flat. One thing about army life, it does not take long to knock you back in shape what with machine gun drills, rifle drills and route marches. You soon forget about holidays.

The Germans were advancing along the African coast and we were ordered to take up defence positions in Egypt along the Western Desert. With us were a number of Indian and British troops and for the next few weeks we had to experience life in the desert. On fine days everything was clear and beautiful but the nights were very cold. Every second or third day, the sand storms started blowing and we could not see a few yards in front of us. We had to gulp down our meals in minutes or have a dish full of sand. When we awoke in the morning we had to dig ourselves out of the sand. There could have easily been a foot of sand all over us. They say life was not meant to be easy and that was certainly true in the Western Desert.

There was no enemy action along that front and after a few weeks a more urgent need developed. The situation in Syria became critical and our presence in the north became urgent, so back to Palestine to prepare for an attack on Syria. The Vichy French were in control of Syria and their collaboration with the Germans made the northern border of Palestine very vulnerable. I was very happy to return to Palestine. The thought that I might manage to see my mother and the rest of the family was very heartening.

This time we camped in the middle of Palestine near Affulla, which was closer to Safad. One evening Johnny and I hired a taxi and went to Safad. We could not get leave passes so we had to be back by day light. It was expensive but a most enjoyable time to spend an evening with my mother, Rachel and Ayala and also lots of our friends. It was a two hour drive so by the time we got back it was about time to get up. Needless to say, Johnny and I were very tired boys the next day. The main thing was that we were not caught.

We spent about two weeks at Affulla camp. Next door was Kibbutz Merhavia and it did not take us long to find out the friendship and hospitality that Kibbutz people can offer. Imagine one thousand unexpected guests turn up for supper! That’s exactly what happened. We filled the dining room, soldiers on one side, Kibbutznicks on the other and dancing in between. These were mostly Jewish folk dancing and Johnny and I joined in and were envied by most of the others. Then the soldiers sang Waltzing Matilda and other songs. What a lovely party it turned out to be. After all the singing and dancing they served supper. They must have used their entire week’s rations to feed this army. They certainly excelled themselves and a close relationship developed between us, even though we were there for only a short time. Before we left we raised one thousand pounds and bought them a grand piano.

One close friend of mine said to me, “Josh Greenfield, you knew of this sort of life and left to come to Australia. You must be an idiot”. Maybe I was but did I really know this sort of life? Safad may only be two hours away by car but it might as well have been in another world. Then again, was not Gal-Ed (the farm my friends and I tried to establish many years ago) meant to be this sort of life? How could I possibly explain all this to my Australian soldier friend without him coming to the conclusion that I was an idiot?

The day came for us to move up to the border of Syria. It was supposed to be a top secret move. We were to leave the camp at Affulla under cover of darkness at two o’clock in the morning and a total security clamp down was in force. As the convoy of trucks and machine gun carriers were approaching the main road we noticed hundreds of our friends from the Kibbutz standing by the road side waving us goodbye and good luck. They kept awake to see us off. So much for security amongst friends and we were all very happy to see them waving to us.

We reached the border at the crack of dawn and the march into Syria was in full swing. At this stage there was no enemy resistance and we just rolled along. As the sun was rising above the mountain peaks I found myself viewing familiar surroundings and a sense of deep emotions overtook me because there to the left of me was Ain-Ebel and these are the hills where the family Greenfield were scattered trying to escape the massacre that nearly destroyed that village. This is 1941, exactly twenty years later.

Memories of the Arab conflicts that I grew up with were flashing back in my mind as I was sitting next to my driver in the machine gun carrier. I wondered if any of the inhabitants remember what happened to their village in 1922 and what they were thinking of this army advancing on their land. I also would have liked to ask some of the elders if they remember my grandfather and my family. I had no opportunity to ask these questions. We had to march on. The French Army, through their Foreign Legion, were taking up defence positions along the Litany River which was a full day’s travel away.

There was a small skirmish as we approached the Thursday market village. A few French gendarmes fired on the advance column. The skirmish did not last long and as we drove through we saw a few dead horses and a couple of women crying. I thought it was rather crazy for a few gendarmes to fire on an advancing army. From there we advanced along the coast road towards the Litany River.

We arrived at our destination late in the afternoon and preparations were underway for the attack on the French positions along the River. They had blown up the bridge and a new one had to be erected. The terrain was not suitable to use the machine gun carriers. We left the driver and the carrier at the base and the rest of us equipped ourselves with light machine guns. Under cover of darkness we climbed the mountains overlooking the river. We took up our positions to give covering fire for the troops attempting to build the bridge and cross over to the other side.

At the crack of dawn all hell broke loose. Everybody was shooting and our target was the other side of the river. Artillery shells from our rear were flying overhead. It was a non-stop bombardment and for the first time I found myself in a real war. It was not a one way battle.

The French were well dug in. they had huge concrete bunkers and no shortage of gun power. By the time the sun rose, our engineers managed to erect a new bridge and our troops established a spearhead on the other side. From then on it was just a matter of time before we cleaned up the remnants of the French Foreign Legionaries. This action was quite costly. We lost a great number of good men. A friend of mine also using a machine gun a few yards away from me had a bullet go through his arm and he had to be evacuated. Fortunately he did not lose his arm.

We captured a number of prisoners. They had to be searched and then taken back to base headquarters. There they were given an option to join the Free French Army which was being formed by General De Gaul. One prisoner, whose belongings I happened to be going through, appeared to be extremely cheerful. I wondered why this man was smiling. I could not ask him in French so I decided to try my Yiddish/German and to my amazement he answered me in perfect Yiddish. “You are Jewish too, we are brothers”. He was ready to hug me which was rather embarrassing in front of the other soldiers. He was happy the war was over for him. He had been in the Foreign Legion for the past five years and had a wife and daughter in Tripoli. He carried their photos which he showed me. He also gave me their address. I promised to look them up if I got there. As things unfolded, I did not get an opportunity. He also considered joining the Free French Army. We shook hands and hoped to meet again, next time on the same side. To think that only a few hours earlier we tried to kill each other.

We had to regroup. We won the battle but our objective was still a long way off and many more battles were ahead of us. The French under the German influence were not going to give in easily.

Our next target was the city of Siddon, a nice little place along the coast. We took control of the city and also captured many more prisoners.

Our Battalion Head Quarters called on me when they needed an interpreter while dealing with some of the local Arabs. As a matter of fact, when we first arrived in Palestine they offered me a job to become an official interpreter for the Australian Army which would have meant a promotion and a base job. I rejected their offer on the grounds that I did not join the army to have a base job and besides I wanted to be with the boys. I was quite happy to do the odd translation.

One day while on patrol duty through an Arab village, we were confronted by the local chief with an urgent request for food supplies. He explained to me that they were on a starvation diet because of all the military actions around them I promised to take up his case. My commanding officer was sympathetic and the following day we had a truck load of food supplies, mostly wheat, and drove it back to the village. The poor people did not stop hugging and kissing us.

There was another big battle looming ahead. The French had large fortified positions at Damure, which was on the outskirts of Beirut and we knew we were in for a rough time dislodging them from these positions. The battle was in full swing. Our troops, under cover of artillery fire, were advancing through the orchards, me leading the way on the main road in my machine gun carrier. To the left of us was the beach and that was full of mines. We were approaching a sharp bend in the road and I noticed a big commotion around us. Troops were scattering and taking cover. With the noise of the carrier engine I could not hear what was going on. I asked the driver to pull up while I jumped out to investigate. I was half way across the road towards the orchard when to my horror I saw a huge French tank coming around the bend and like a flash the tanks big guns scored a direct hit on my carrier. The driver and gunner had no chance. Hopelessly, from the edge of the orchard, I saw smoke and scattered pieces of what used to be a machine gun carrier. I was terribly frightened and stunned at what I had just witnessed. Two good friends of mine I shall never see again. I did not even have a rifle with me to defend myself and I heard somebody say that French troops were following the tanks.

I saw an officer coming along through the orchards carrying two anti-tank bombs so I tagged along with him. He knew what had happened to my carrier and he was so surprised to see me. Naturally he thought I was also in the carrier when it was blown up. I told him the circumstances and he looked up and said “Somebody up there must love you. Better come along with me”. The idea was to try and sneak behind the tank and plant one of the bombs on it. That task proved hopeless. There was too much fire power coming from behind the tanks.

Headquarters were fully alerted to the situation. They moved up the artillery units, fired point blank at the tanks and we then marched on. A few days later the French surrendered and the road to Beirut was just ahead of us. Beirut was declared an open city and there was not going to be any further fighting. It took us a whole month to get there and we lost many good men.

The Vichy French lost their last outpost and our ride into Beirut was very spectacular. The people turned out in their thousands and waved at us. I was sure they were very pleased to see us as well as knowing that their beautiful city was spared from destruction. Beirut was certainly a beautiful city. It was then claimed to be the Paris of the Middle East. I’d not been to Paris but I certainly enjoyed what I could see of Beirut.

Our Battalion was given the honour to garrison the city and for the next three months we had the best time in the entire five and a half years of military service.

Our headquarters in Beirut was situated in the middle of the city, a large building surrounded by a high brick wall and a large entrance gate. The building was set well back from the main road. A 24hour guard was mounted at the gate. A short distance inside the entrance was the guard room, where the relieving guardsmen rested between shifts of two hours on and four hours off. The total guard consisted of three men and a corporal in charge. When my turn for guard duty came, I chose three men from my section and we drove over to Battalion Headquarters to relieve the old guard. Nothing eventful happened until the following morning, when the Duty Officer came over to me said, “Corporal Greenfield, we are expecting the Field Marshall to pay us a visit at 11.00 hours. Make sure to line up your men and give a “present arms” salute as he drives past. You should be able to handle that Corporal”. “Yes Sir,” I replied.We had practiced many “present arms” drills in the past, but never in front of a Field Marshall, of course. As a matter of fact, I had never seen a Field Marshall before and probably wouldn’t see much of one this time either as he drives past us.

That’s what I thought. At 1045 hours two soldiers on motor bikes came riding through the gate and told me that the Field Marshall would be arriving in 15 minutes. I lined my two men up inside the entrance and gave them a quick inspection. I also instructed the man at the gate to give a “present arms” salute as soon as the motor car with the Field Marshall arrived.

At exactly 1100 hours, six sergeants on motor bikes came through the gate, followed by a large black limousine. I gave the order “present arms” expecting to see a returned salute from the back seat of the limousine as it drove past. But, what went wrong?

The car pulled up, the driver came out, opened the rear door and there, in full uniform and a chest full of ribbons, stepped out the Field Marshall. He stood to attention and returned the salute. What do I do next? He was supposed to drive past us. I am only a Corporal, the second lowest rank in the army!

I took a quick glance at the Headquarters’ building as if asking for help, but all I could see was dozens of heads hanging out of the windows looking at us, wondering what the Field Marshall was up to and how was the corporal coping with the situation. I knew then that I would not be getting any assistance from Battalion Headquarters. I was definitely on my own.

I could not let him stand there all day with his right arm bent touching his forehead returning the salute, so I gave the order “slope arms”. The men obeyed and the Field Marshall brought his right arm down to his side. I expected him to turn around, go back to the limousine and drive off, but there he was, still standing to attention and looking straight at me.

I have taken part in many ceremonial parades in the past. I was always one of the soldiers taking orders from senior officers, but here was I the one giving orders in front of a Field Marshall. I took a deep breath, then two steps forward, looked him in the eyes and said, “Would you like to inspect the guard, sir”? (The whole two of them!) “Yes, Corporal, I would like to”, he replied. I stepped aside as he walked up to the men. He spoke a few works to each one and then looked at me and said, “Well turned out guard, Corporal”, to which I replied “Thank you, Sir”.

He then made his way back to the limousine. I thought it was worth another “present arms” salute which he acknowledged. He then drove off to the great relief of my Commanding Officer, the rest of Battalion Headquarters and needless to say to me and my men.

A short time later the Duty Officer came over and said, “Congratulations Corporal Greenfield, you managed the situation very well”. I then replied “Thank you sir, but please next time let it be a General, a Field Marshall is a bit too much for a Corporal to handle”.

We went further north to Tripoli, a much smaller city. We did not stay long and moved inland up the mountains where we established camp. The winter was setting in and we experienced the first snow. We were near Mt Lebanon which is covered with snow the whole year round. The French had an Army skiing school on Mt Lebanon and my section were sent there to guard the place for a few days. It was quite large and well equipped. There I had my first, and last, attempt at skiing. It lasted thirty seconds. I stood up in my skis, went two yards forward, did two somersaults and that was the end of my skiing career.

I received an invitation to my sister Rachel’s wedding. I was very happy for her. She was marrying Yoseph Toister, whom I knew well. He was from an old established family in Safad. They had a large grocery business by Safad standards. As a matter of fact, Sam Toister, my friend who travelled with me to Australia, was his cousin. I was really looking forward to being at Rachel’s wedding. I applied for leave which was granted. I wrote to my brother Moshe and arranged to meet him in Haifa to help me buy a wedding present and then travel together to Safad.

It was a lovely wedding; not very big, but most enjoyable. It was held in one of the local hotels. My father was greatly missed. I stayed on in Safad for two more days after the wedding and then it was time to say goodbye again. Little did I realise then that this would be the last time I would ever see my dear mother, and my dear brother Moshe,

By the time I got back to camp, Japan had already bombed Pearl Harbour and was advancing in the Pacific. Our presence in this region became urgent. We said farewell to the snowy mountains of Syria and in large convoys of trucks made our way back to the Suez Canal to embark on escorted ships to somewhere in the Pacific.

We arrived at the port city late at night and were billeted at the British army barracks inside the perimeter of the port. We had to erect special tents to accommodate the large number of Australian soldiers.

. The port area was guarded by British soldiers with Egyptian administrators. The township of Suez was a few kilometers away and was declared out of bounds for the Australian soldiers. Outside the port area were a number of cafés and a few shops selling souvenirs. There were no restrictions to visit the cafés and shop around.

After a short night’s sleep and breakfast, there was not much to do. We had to wait for the ship to be loaded and the rest of the troops to arrive. We were told this would take a few days and it was up to us to make the most we can out of the spare time we had, provided it was within the laid down regulations.

A couple of my friends and I wandered across the road to the nearest café to look around. The place was bigger than we thought and well equipped. Apparently the British soldiers spent a fair bit of their leisure time there. They did not have Australian beer, which was rather disappointing, so the British lager had to do. The waiter serving us the drinks was very intrigued how an Australian soldier speaks such fluent Arabic. This is what I had intentionally done. In a quiet voice I asked him not to repeat what I was going to tell him, knowing very well that he’ll do just the opposite. I told him that I was not an Australian, but the grandson of Amir Abdullah (King of Jordan) and it was his wish, as a matter of diplomacy and friendship that I serve with the Australian army. His eyes nearly popped out as he bowed to me. I watched him whisper to the other waiters. They made a point to walk past our table looking at me and bowing their heads. I thought it was time I let my soldier friends in on the joke and they were just as amused.

A few more days of the same was getting rather boring, so we decided to do what we were not allowed to do. Six of us hailed a taxi and piled into it and told the driver to take us to the township.

Suez was rather a small place with a few narrow streets, which were not terribly clean. We bought a few souvenirs. The cafés were not as clean as the one at the port. After a short look around I thought I had enough and was prepared to go back. Unbeknown to me, one of our boys became involved in an argument and a street fight developed. Before you could say “Jack Robinson” we were confronted by dozens of yelling, stone throwing Egyptians and more were coming. It called for a hasty retreat. I did not have a chance to tell them about my “Royal Title”. The faster we ran we could still feel the stones hitting our backs. Luckily no serious damage was done, apart from our pride. None of us could ever recall being chased out of town.

After returning to the barracks and licking our wounds, we decided to counter attack. How could we possibly explain such humiliation to our future children?

It was getting dark by now. We loaded our rifles and declared war. But how are we going to pass the British guards at the gate without them asking questions and making an urgent phone call? I got a brain wave. Why not line the men up in a disciplined manner, rifles at the slope and a corporal marching beside them as if we are going to a special guard duty?

It worked. The British guard stood to attention and gave us a salute as we marched past. We got to the main road and confiscated the first empty taxi that came along. He can forget about the fare, he must have been one of chasers. I told him to pull up near the café on the main road opposite the place that the chase began.

I instructed one of the men to stay with the taxi and make sure he does not get away, because we will certainly need him before we finish. The five of us marched into the café. I had a gun in my hand while the others had their rifles at the ready as we approached the bar. I asked the proprietor where he was this afternoon when we were chased out of town. He swore he did not know anything about it. Of course I did not believe him and ordered him to put half a dozen bottles of wine in a bag as punishment for the embarrassment they caused us. A couple of the young men tried to make a move towards us, but when we pointed the guns at them they changed their minds and sat down.

Our next visit was to the café a few doors further back, giving out similar punishment. After making our third call, we thought we had our revenge. We picked up our loads and made our way towards the taxi, but something went wrong. There was no taxi. The man in charge of the taxi told us that he wanted to join in the excitement and the taxi driver told him he wouldn’t go away. There we were, fully armed with two dozen bottles of wine and no transport to get away.

As we were looking around and wondering what our next move would be, there appeared half a dozen Egyptian police cars surrounding us and ordering us to lay down our arms. I thought the odds were stacked against us and told the men to do what we were told. We were then bundled into the police cars and taken to police head quarters. There we were locked up while they made contact with the Australian Army Head Quarters.

It was midnight when our sergeant accompanied by the platoon officer arrived to get us out, after promising there would be a court marshal to decide our punishment. The next morning our ship pulled out on our way to Colombo.

We were then ordered to report to the ship’s captain on the bridge. There he was sitting at his desk and next to him sat a high ranking army officer. They wanted to hear from us exactly what caused well-disciplined soldiers like us to act as we did. I told them the reason and they looked at each other. The captain then said, “You boys have a bigger task ahead of you. Case dismissed.”

As we sailed through the Suez Canal, I could not help reflecting that here I am crossing the Suez Canal for the third time in as many years. Me, a young lad from Safad, and the furthest I had travelled in seventeen years was to Haifa, a two hour bus trip. How many thousands of miles had I travelled since then and how many thousands more lay ahead of me.

I had no answer to that question as the convoy made its way along the Canal. All we knew was that we were going to engage a new enemy, the Japanese Imperial Force.

Our transport ship was just that. We were each allocated a few feet of floor space below deck where we placed our equipment and personal belongings. We were issued with hammocks and, provided the weather permitted, we slung them on deck. Otherwise it was over the dining tables or where ever you could see spare space. The real problem was finding your way back if you had to get up during the night. When the sea was rough and the ship’s propellers rose above the water this caused a loud annoying rattle, which unfortunately happened often. We managed as best we could. Most days we spent on deck and our main past time was playing cards. As things unfolded, this was to be our way of life for the next nine weeks.

Our immediate destination was Colombo. There we anchored in the harbour for the next few days waiting for the convoy to reassemble and for further orders as to our final destination. There was no shore leave and we had to do our purchases from the locals when they came over in their loaded boats. They threw us a rope and if we fancied something they put it in a small basket which we pulled up and sent back the money. We did learn one thing that a lot of bargaining had to be done before the money was sent back. These activities filled in our days while the chiefs decided our future.

A few days later we were on the move again. This time our destination was Java, Indonesia to stop the Japanese advance south towards Australia. We were issued with instructions and the convoy was sailing full steam ahead. We had plenty of time to carry on with our card games. By now I had myself a good bridge partner and we took on all comers.

I woke up one morning on deck and noticed something different. Every other morning the sun rises on my right side, but not this morning. My first thoughts were that we were zigzagging to avoid enemy submarines. Then a news flash came through. Java had already been captured by the Japanese and we were returning to Colombo. I was hoping they would give us a few hours shore leave as my legs needed stretching badly. As it happened the ship needed to replenish supplies and was tied up at the wharf. We were given shore leave till midnight. It was our first touch of land in over three weeks and we made the most of it. I was back at midnight but could hear many trying to climb up the gangway in the early hours of the morning.

But where to next? The ship having taken on supplies moved out and dropped anchor in the harbour and we were back bargaining with the natives and playing cards. This went on for a few more days. Big decisions had to be made. Singapore was being considered, but could we get there on time? Apparently not. The Japanese were advancing too fast and there was only one place left. Back home to Australia.

It was a bright day. The sea was calm as the convoy pulled out of Colombo for the second time. There were no unusual incidents and we went on looking at the sea and playing cards. On the third day we noticed the convoy performing strange manoeuvres. All the ships were turning around and going back. But why? And where to? A few hours later we got the answers. A large naval battle was developing between the American Navy and the Japanese in the direction we were heading and that is no place for a troop carrying convoy. So it was back to Colombo for the third time.

It took the Americans a few days to get the better of the Japanese and then the all clear signal came through. Once again we set sail. After nine long weeks at sea our transport ship tied up at Port Adelaide. What a lovely feeling it was to step ashore on Australian soil. I really felt that I was an Australian.

I thought Adelaide was a beautiful city. The streets were wide and clean and the gardens were beautiful. We camped not far from the city proper and had many opportunities to roam through the city. The people were extremely nice to us. They recognised the colour patches on our uniforms that showed we were returned soldiers from the Middle East and accordingly they offered us hospitality and respect. We in return opened our camp for the people to visit us. I remember on one open day I gave a few rides on my machine gun carrier to some of the young visitors. They enjoyed the bumps on the rough rides.

The troops on the transport ship that brought us to Adelaide were a mixed lot from all states. Most of the 2/16 Battalion soldiers were on a passenger ship and went direct to Fremantle and were given home leave. The carrier and transport companies that finished up in Adelaide had to wait some time before we got our leave passes and railway transportation to take us to our home town of Perth. I was naturally looking forward to seeing my father, my relations and friends.

We boarded the train at Adelaide station to take us on that very long journey across the Nullarbor Plain. First we had to change trains at Port Pirie, then another train to Kalgoorlie and then another change had to be made all because of the different rail gauges that were in operation in those days. We had engine trouble going through the Nullarbor and another engine was sent over to pull us the rest of the way to Kalgoorlie. That meant a lot of wasted time stranded in the middle of the desert and nothing to see but sand. Five days later we reached Kalgoorlie. From there on it was an easy ride to Perth.

Eighteen months ago I was on a train to Fremantle on my way to the Middle East. How much has happened since. How many of the boys that were on that train are no longer with us. How many broken hearted parents, brothers, sisters and sweethearts will not be at the

station to greet their loved ones because their bodies were left somewhere on the hills of Syria. These thoughts were going through my mind as I was waiting at Perth railway station to catch a train to Cottesloe to see my father.

We were very happy to embrace each other. I could not help feeling how lonely my father must be. It was four years since he saw his wife and other children. Was this going to be one of his shattered dreams? Was this new life in a new land also going to end up as all the others did? From where we stood the future did not look very promising. There was still a big war ahead of us and the chances of my mother coming to join him here in Australia were very remote. This time it may not be a lit match that will put an end to his fourth attempt to build up a future for himself and his family. What an unjust fate some people are born into.

I had to control my emotions as we sat down and talked about the last eighteen months and there was a lot of talk about my mother, my brother, and my sisters, and as always Ain-Zeitim. I did correspond with my father but how much can you say in a letter. Besides all our letters from overseas were censored by our commanding officers and therefore we avoided any personal matters.

My father had a young girl helping him to serve in the shop and give him the occasional break, but I did not think there was too much of that. My leave pass was only for two weeks and there was a lot I wanted to catch up on, especially to see the cousins Lore, and Hope and Anne. The latter corresponded with me while I was away.

My friend Charlie, a soldier I met on board the transport ship coming home, lived around the corner from our fruit shop. He made a habit of calling on me at ten o’clock in the morning as soon as the hotel opened to have an early drink with him. We also met up with a few other soldier friends at the Albion which was around the other corner of our street. That habit took up a fair bit of my holiday time. Before long my leave pass expired and it was time to depart again.

I said goodbye to my father and made my way towards the railway station. I looked back and saw him waving to me. On many occasions when I said goodbye to my mother she had family and close friends around her, but here my father stood by himself with nobody to comfort him.

I boarded the train to the Army Barracks for yet another journey. This time was to confront the Japanese somewhere in the Pacific. The Japanese were well trained in jungle warfare whereas the Australian Army was not. That was something we had to learn fast.

After changing trains many times and crossing every mainland state we finally reached our destination, the Tablelands of Queensland. The camp sites were ready and our jungle training started in earnest. For the next three months we were marching up and down slippery jungle tracks, crossing many rivers, learning to sleep in our wet outfits and putting up with millions of mosquitos.

Our machine gun carriers were obsolete. Instead we formed human carriers with one man carrying the tripod, one the machine gun and the third man the ammunition. All this plus our personal gear made quite a formidable load to cart around jungle slopes. The army had its own daily news letter called Pigeon Post. One morning after breakfast I received a message to report to Battalion Headquarters. The Commanding Officer asked me if I read this morning’s Pigeon Post and I said “not yet”. He then showed me an article which read:

“A bomb was thrown through the front window of a fruit and vegetable shop in Napoleon Street Cottesloe last night. The owner of the shop, Mr Greenfield, was asleep in the back room. He was not harmed. The only damage was to the front of the shop”.

I was very upset and the officer asked if I wanted a special leave pass to visit my father. I told him that if I left today it would take me two to three weeks to get there and what could I do when I got there.

I knew that the Commanding Officer was the editor of the West Australian daily before he joined the army and if the bomb was thrown because my father was Jewish, then an article in the newspaper condemning such vandalism would do the cause more good than my leave pass. He appreciated my opinion and a few days later a large article appeared in the Western Australian and amongst all the other words of condemnation it also read “How can they do such a cowardly act to a man whose son is away fighting for this country”. My father later told me that his business took a big leap forwards.

I heard two soldiers were later charged with this offence. Apparently they bombed the wrong shop. A day earlier, after having a few drinks, they were involved in an argument with the Greek shop proprietors and decided on revenge. My father’s shop was the nearest fruit shop when they got out of the station and mistook it for the Greek shop.

Our training was nearing completion and soon we would be ready to confront the Japanese and stop their southward advance. At this moment the threat to Australia was real. The Government even considered they may have to evacuate the northern part of the country and drew up what was to be known as the Brisbane line.

New Guinea was our destination. If we could stop the Japanese taking over that country then Australia would be saved. As a farewell gesture, but more as a morale booster to the people of Queensland, all our military units marched through the streets of Brisbane. The people turned out in their thousands, cheering and waving. It was a nice finishing touch to our hard months of training. We embarked at Cairns and the trip across to New Guinea was short and uneventful and we were to soon disembark at Port Moresby. We had to clear the wharf in a hurry because of the threat from enemy aircraft and we went inland to established camp.

The Japanese were infiltrating through the Kadoka trail in the Owen Stanley Ranges and that was where we had to meet them head on to stop their advance on to Port Moresby. The task was difficult and going along the trail was a lot harder than we anticipated. The Japanese were well trained for these conditions.

Two weeks later I caught that dreadful disease Malaria and had to be evacuated to Port Moresby Field Hospital. There I spent two weeks, and another week convalescing. By that time I was half a stone lighter and a lot weaker. I rejoined the part of the unit patrolling Port Moresby perimeters.

On one of these patrols which was to be for one day, we lost our way and for three days we climbed mountains, crossed rivers and not a sign of our camp site. We did have a compass but that was not much help. Usually on a day patrol we carried a day’s rations plus an emergency box of a couple of biscuits and a few hard chocolates. On our second day we finished the emergency rations and from then on we looked for wild berries and boiled green paw paws which tasted terrible. I started to dream about all the food I was going to consume if we ever got back to camp.

On the fourth day, tired and hungry, we spotted an Australian Army outpost. What a lovely sight that was and I was going to eat them out of their whole month’s rations. That’s what I thought, but after a cup of tea and a few biscuits and cheese I could not eat anymore. My stomach had simply shrunk.

Another serious disease which affected a lot of our men was “Scrub Typhus”. So between enemy action and sickness we suffered many casualties. By the time our Battalion was relieved we could only muster one hundred and thirty men. We paid a very high price but it was the first defeat the Japanese suffered since Pearl Harbour and the tide of war had turned against them. This campaign lasted seven months and we were then sent back to Australia to recuperate and reinforce because there was a lot more to come.

We landed back in Cairns and spent a few days there before we had home leave, which meant another long journey by train. Three weeks later we arrived at Perth station and once again I was looking forward to seeing my father. It had been nearly twelve months since we last saw each other. I found him to be in good spirits and we spent a lot of time catching up on old times. We discussed the bomb episode in the shop. What a frightening experience it was for him to be woken up by such a bang and shattering of glass. His first thought was that the Japanese were already there. It was a terrible feeling especially as he was on his own.

I caught up with the cousins and old friends and also spent a fair bit of time shuttling between the fruit shop and the Albion Hotel. Having a few drinks with the boys became part of my leisure time. I learned to live for today as if there was not going to be a tomorrow. Then it was time again to say goodbye to my father. We gave each other a hug and I felt sure we had similar thoughts. How much longer is luck going to hold out? Will we see each other again?

The long journey across the Nullarbor Plain for the fourth time, the broken down engines and the changing trains were all so familiar events. How many more times? Hopefully it will be only once more, to come home. But fate had other ideas. On this occasion we had a few day’s break in Melbourne and for the first time I had a chance to have a good look around. Little did I realise then that it would be in this city where I would find peace at last.

When I was in Perth I was told that my cousins Joe and Bertha Lore were now living in Melbourne. I got their address somewhere in Carlton but unfortunately no one was home when I called. I had a good look around Carlton. To think I was only a few hundred yards away from where my future wife lived. Maybe I saw a pretty young lady smiling at me.

Then the journey continued back to North Queensland for more training in Jungle warfare. The Japanese may have lost a battle but not the war. They still had large forces along the Markham Valley and the famous Shaggy Ridge in New Guinea. Our next task was to clear them from those areas and the rest of our country.

A few days before the Battalion was ready to leave I got my second attack of Malaria and again I had to be evacuated to hospital. These attacks don’t get better. I was a very sick boy and the doctors injected Quinine into my veins. I recovered and after some convalescence was ready to rejoin the unit. With other reinforcements I embarked at Cairns for Port Moresby.

Before continuing the journey some mail caught up with me and amongst them was an invitation to my brother Moshe’s wedding. I was very happy to hear he was settling down to a normal life. I met his future wife Rachel when I visited him in Jerusalem during one of my days on leave from Julis camp. I sent him a congratulations cable and a few pounds for a wedding present.

Having attended to all these matters I was ready for my very first aeroplane flight. To get to the Markham Valley to join the Battalion we had to fly over the Owen Stanley Ranges. It was quite an experience. Every time we hit an air pocket and the plane dipped I thought “Goodbye Joshua”.

Our transport plane was escorted by an American fighter plane and for his amusement, because it certainly was not for ours, he brought his plane close to ours, wings nearly touching. Through the window we waved him away but he was having too much fun. I don’t know what our pilot thought of it, probably also enjoying it at our expense. I was glad when the plane touched down. Our troops had already advanced through the Markham Valley and were approaching Shaggy Ridge when I caught up with them.

The going was hard and the Japanese were well dug in along the mountain tops. Parts of the mountains were razor edged and very tricky to advance, but slowly we were fighting our way through.

One night a Japanese patrol penetrated behind our advance lines killing a whole section of our Battalion. To prevent a similar occurrence I was assigned the following night to mount a lookout post along the track that the Japanese used. Under cover of darkness I took three men with me and in turn one of us kept watch. Sometime after midnight the man on duty shook me and whispered, “I think they are out there”. I sat up and sure enough there were creeping sounds just ahead of us. I had to think quickly as obviously they did not know we were there. If I woke up the other two men the noise they may make would give our position away and the odds would be against us. I decided to sneak up and give them a few bursts of automatic gun fire and catch them by surprise. I asked the man on duty to keep me covered and step by step I made my way towards the intruders. All of a sudden I was hit all over with feathers and screams. After losing a few heart beats I sat down and wondered what the hell was going on. Surprisingly I did not start shooting. I had an instinct it wasn’t the Japanese. I soon realised what had happened. I stepped on a large birds nest and what’s more, the noises we heard were that of wild pigs roaming in the night. We lived to fight another day.

The Japanese were determined to hold on to their last post on Shaggy Ridge, which was the Pimple. They were well dug in and had plenty of arms. Our task to dispose of them was not easy. Before our troops moved up, the Pimple was continually shelled by our artillery units and bombed from the air making our task a bit

easier. Finally the Japanese lost their last foothold on Shaggy Ridge and our objective accomplished. New Guinea was free at last.

It was time for us to have a well earned rest. We flew back to Port Moresby on our way to Australia. The day before we embarked I picked up a nasty ear infection called Tropical Ear. That was the most painful experience I had ever been through. I had medical attention but it was not getting better. All I remember of the ship that brought us back to Australia was lying there in agony. I lost count of the aspirins I took. If I was able to get close to the ship’s rails I might have thrown myself overboard. When we arrived in Cairns I was taken to hospital where they either gave me something or I just passed out because I had no recollections of the next twenty four hours.

A few days later I felt better and went back to our unit ready to board the train for that all too familiar long journey to Perth. After all the experienced we had been through in recent months, those train journeys started to feel like a luxury holiday and the thought that we were going to spend some time with our families and friends made that trip across the Nullarbor Plain much more bearable.

I was glad to embrace my father again. This time it was the shortest period I had been away, only about seven or eight months, so things had not changed. The business was carrying on as usual and a new girl helped my father in the shop. She looked very nice and was doing a good job. My father seemed to be very concerned with not only my activities but his own future. With Rachel and Moshe married and Ayala soon to be, there was no way my mother would leave them and come to Australia. Nor would he have liked her to.

My father had made up his mind that once the war was over he would go back to Palestine. Financially he would not be better off so what would he do there? Of course he was looking forward to seeing his wife and children, but what about me? I had no answer for him. The war was a long way from being over. The Japanese were still putting up a lot of resistance and occupying many parts of the Pacific. How much longer is luck going to hold out? I knew of so many good friends who paid the ultimate price. No, I had no plans for the future. If tomorrow comes I’ll most likely meet the boys at the Albion Hotel and that’s as far as my future plans went.

My fourth goodbye to my father was the most difficult of all. The look in his eyes told the story. “How much more has the 2/16 Battalion to endure”? My father had a draw full of newspaper cuttings of all our Battalion’s battle activities. He knew all about Syria, Owen Stanley Ranges, Gona Beach, Markham Valley and Shaggy Ridge. He also kept a close eye on the casualty list which was getting longer every time I said goodbye and the odds were getting much shorter for my survival. I had been in the army now for over five years. I sailed overseas three times, covered many thousands of miles on land, sea and air. I was getting tired and for the first time I shared the look in my father’s eyes. How much longer? The answer to that question was beyond my control. The Japanese were still occupying many of the Pacific Islands. The large oil fields of Borneo were supplying their war needs and that’s where our next objective was.

The train trips across the country brought us to Townsville, Queensland. There we underwent many sea landing exercises which were new to us and we had to learn them fast. I was only there for a short period when my third attack of Malaria struck me and again I was evacuated to the military hospital. Three weeks later I was declared fit enough to rejoin the Battalion and in time to embark to Morotai Island for further landing exercises in preparation for the assault on Borneo. The trip to Morotai took six days.

There were a few letters waiting for me and one of them was from my father. If I needed confirmation about his feelings it was in this letter dated 3rd June 1945. Today, all these years later I still have this letter with the visible sweat stain on it. I wish I could give it an English translation but I cannot. In the letter he gave me a few blessings from the “Torah”. His request was for me to keep it on my body at all times till the war ends then return the letter to him. I fulfilled the first part of his request. I placed the letter in a small plastic folder and carried it in my shirt pocket right through the Borneo campaign. Circumstances prevented me returning the letter to my father personally. Later I thought the letter served its purpose and decided to keep it as a lasting souvenir.

“D” Day came and all preparations were completed. The biggest Armada I have ever seen was making its way towards Borneo. There were troop ships and battle ships as far as the eye could see. On our ship there was a clay model of the coast of Borneo with the landing spots and objections were fully identified. Every soldier on board was aware of his responsibility. The Australian Army had learned a lot in the last five and a half years about conducting a military operation. The attack on Borneo was well planned to the last detail. Our target was Balikpapan, but the coastline was covered with black smoke. Every oil well must have been in flames. A few miles out to sea we climbed off the ship on rope ladders into landing barges. The sea was very rough which made this task a lot harder as we made our way towards the coast.

There was a nonstop bombardment from the air on enemy positions. The war ships were also sending salvo after salvo of rockets and shells from their huge naval guns. The sound of explosions was deafening. It was my most anxious period of all the years of war as we were heading towards a beach covered with flames and thick black smoke.

The barges pulled up close to the beach and we jumped out with all our gear. The water was above our knees. We then raced across and up the slippery hills.

The Japanese were still putting up resistance and causing us many casualties, but eventually we dislodged them and secured a beach head. From then on it was a matter of slow progress pushing them further back. Six weeks later our objective was near completion. The Japanese were losing their foothold on Borneo. They would no longer have all these oil fields to supply their war machines. We lost many good men and I kept thinking how much more is there for the 2/16 Battalion?