WILLIAMSON, Thomas Arthur Raymond

| Service Number: | 69348 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | 16 April 1918, Bendigo, Victoria |

| Last Rank: | Sergeant |

| Last Unit: | 1st to 17th (VIC) Reinforcements |

| Born: | Bendigo, Victoria, 6 November 1895 |

| Home Town: | White Hills, Bendigo, Victoria |

| Schooling: | Not yet discovered |

| Occupation: | Clerk |

| Memorials: | Bendigo White Hills Arch of Triumph |

World War 1 Service

| 16 Apr 1918: | Enlisted AIF WW1, Private, 69348, Bendigo, Victoria | |

|---|---|---|

| 2 Nov 1918: | Involvement AIF WW1, Sergeant, 69348, 1st to 17th (VIC) Reinforcements, Enlistment/Embarkation WW1, --- :embarkation_roll: roll_number: '20' embarkation_place: Sydney embarkation_ship: HMAT Medic embarkation_ship_number: A7 public_note: '' | |

| 2 Nov 1918: | Embarked AIF WW1, Sergeant, 69348, 1st to 17th (VIC) Reinforcements, HMAT Medic, Sydney | |

| 4 Feb 1919: | Discharged AIF WW1, Sergeant, 69348, 1st to 17th (VIC) Reinforcements |

Help us honour Thomas Arthur Raymond Williamson's service by contributing information, stories, and images so that they can be preserved for future generations.

Add my storyBiography contributed by Jack Coyne

Thomas Arthur Raymond WILLIAMSON SN 69348

When Base Records Office in Melbourne received a request in April 1921 from Thomas Williamson from White Hills, near Bendigo to be issued the coveted 1914/15 Star Medal and the Victory Medal they were a little nonplussed and rejected the request immediately.

The office quickly determined that this man had enlisted in Bendigo in April 1918 and embarked from Sydney on the HMAT A7 Medic, which was subsequently ‘Returned’ two weeks out in the mid Pacific. The Armistice with Germany had been declared on November 11, 1918 and any more Australian soldiers in Europe were certainly not needed.

End of story, Thomas had not seen any action; let alone served in the Middle East or on the Gallipoli Peninsula. He would only be eligible for the British War medal.

Further correspondence, including a 'Statutory Declaration' from Thomas would force the Records Office to do some more digging.

In his Statutory Declaration, Thomas stated that when he enlisted he showed the Recruitment authorities in Bendigo evidence that he had served a total of 646 days with the Second Infantry DEO Rifles, South African Army. The Recruitment Authorities acknowledged this and would write on his Attestation papers that 358 days on active duty in German South West Africa, plus 288 days of active service in the Union, the South African Union were served.

In late July 1921, Base Records Office Melbourne would now write to the War Records Office in the South African capital Pretoria to ascertain whether Thomas’ statement was true and if so, determine whether any medals had been awarded or could be awarded for such service.

The War records Office in Pretoria would not respond and are again prompted nearly three years later. Finally on August 22, 1924 the following is received -

‘With reference to your minute dated the 29th July, 1924, I beg to inform you that the 1914-15 Star and Victory Medal in respect to the above described have been issued by this Department – at the time of issue I had no knowledge of his service with the Australian Forces’.

So 22 year old, Thomas Williamson, had already fought just under two years for ‘King and Country’ against the Germans. He would also state in his Statutory Declaration that he had been wounded GSW (Gun Shot Wound) with no detail on what part of the body nor the severity of the wound.

His wound or the end of the conflict enabled him to be discharged from the South African army as Thomas was able to make his way back to Australia and Bendigo and be working as a Clerk in 1918. At this stage of the war numerous Troop ships would have been passing through Cape Town on their way back to Australia to return the sick and wounded in order to make return trips with fresh recruits.

On enlisting on April 16,1918 at the Bendigo Town Hall, Thomas stated that he was born in Bendigo on November 6, 1895 and listed his father (also Thomas Arthur) as his ‘Next of Kin’. However, his father did not live in Bendigo, but rather at 18 Trill Road, in the suburb of Observatory in Cape Town.

The question of how a Bendigo born lad, ends up fighting for the Union of South Africa against the Germans in Africa in1915, remains a mystery.

‘The Southwest Africa campaign was the only World War I campaign planned, executed, and successfully completed by a British Dominion (The Union of South Africa). German Southwest Africa (now Namibia) was a large territory, which was six times the size of England and was Germany's second largest colony. German and Boer settlers in both Southwest Africa and South Africa were called upon to support the small German army contingent of approximately three thousand. South African forces raised were considerable in comparison (fifty thousand) and a fresh Boer uprising was put down in 1914.

On July 9, 1915, the German forces surrendered. The campaign was completed efficiently with minimal loss of life. The South African forces lost one hundred thirteen killed to the Germans 1,331. (Source - http://www.worldwar1.com/tgws/swafrica.htm)

Thomas had every right to say he had done his bit. However, in the April of 1918 he would put his hand up again.

Three weeks after enlisting, Thomas would entrain to Melbourne and move into the Broadmeadows Depot Battalion in May1918. He would spend a month there before being assigned to the 10th Reinforcements for the GSG Victorian Battalion. His prior military experience was soon recognised and on July 1 he would be made ‘Acting Corporal’ and whilst still at Broadmeadows made ‘Acting Sergeant’ in October. In late October they would entrain to Sydney in preparation for taking their troop transport to the European front.

No doubt, Thomas and the Victorian recruits boarding trains at Spencer Street would be reading the favourable news stories coming from Europe. In late October French, Commonwealth and freshly arrived American forces were hastening the German retreat, breaking through sections of the fortress known as the Hindenburg Line. So it was fairly certain they would have known they were in a race against time to get to the front to see action.

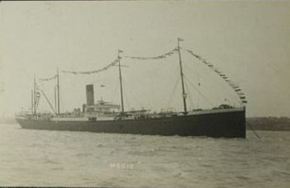

Arriving in Sydney they would embark on November 2, 1918 on the HMAT A7 Medic, possibly the last Australian troop ship to leave for war. The Medic was well known by the Australian forces, as it was a key troopship for Australia during the Boer War, some 14 years before its re-engagement for the Great War.

The HMAT Medic would be 9 days at sea when the Armistice was signed. The ship would be cabled to return to Australia however, the Captain would make a stop in the capital of New Zealand, Wellington on the return to obviously refuel and provision.

The ship would dock back in Sydney on 12 December 1918, however, it was not until a week later that the first reports of events on board HMAT A7 Medic would start seeping out.

On December 17, 1918 The Herald Newspaper in Melbourne ran the headline - ‘The Martyrs of the Medic’

'The public has been roused to indignation again and again by revelations of incompetence on the part of those responsible for the safety and well being of our soldiers. When the facts become known, the Indignation regarding the culpable blundering that occurred in the case of the Medic will be intense. That vessel, which was carrying troops to the front, was recalled to Wellington, New Zealand, owing to the cessation of hostilities, and at the time influenza was raging throughout the Dominion. The Information was at the same time given that the port was infected, yet nearly all the officers and some of the privates were permitted to land. They brought back with them the infection, and the vessel became a lazar-house. The conditions, if one quarter of the allegations made be true, were in the highest degree scandalous, the arrangements for the segregation of the sick being totally inadequate. The result was that numbers of the men contracted the disease, and before Wellington was left 28 of them were burled ashore. When Sydney was reached there was a lamentable delay in landing the men at the quarantine station, where decent living conditions obtained, and so the authorities- have gone on from blunder to blunder throughout the entire length of the pitiful story'.

The Melbourne Press would be outraged over this event with the Sydney Press adopting a less vigorous tone. Criticism or scandals of this nature of the Nation’s Naval hierarchy largely based in Sydney were not welcomed at a time when the country was still celebrating news of the end of the war. The repatriation of over 160,000 Australian men based in France and England was their major priority and would result in much criticism over the following two years.

One Sydney paper did however cover the issue – The Sydney Daily Telegraph reported on December 11, 1918 the following – THE MEDIC. Serious allegations. MELBOURNE, Tuesday. —'The first batch of convalescents from the vessel Medic were detrained at Broadmeadows this afternoon. Questions regarding conditions on board, several of the men painted a gloomy picture, in most uncomfortable surroundings, and the food was of a very poor quality and meagre quantity. No effort had apparently been made to provide for their comfort. Porridge, containing weevils, had been served to invalids, while men had been compelled to lie in boards. They had been worse off as far as comfort and food were concerned, than If they had been in the trenches'.

Unsurprising, a Naval enquiry into the deaths on board the HMAT A7 Medic was held in early 1919 with the Naval Officers finding no case against the Captain and Officers of A7 Medic.

Thomas Williamson would be one of the lucky ones making it back to Sydney. We would read on the final page of Thomas Williamsons Service Record - November 27, 1918, ‘Seriously ill in Quarantine, Relatives not advised.'

Thomas would fortunately recover and return to Bendigo. Whether he saw his 1914/15 and Victory Medals that the Union of South Africa awarded him, is not known.

Acting Sergeant Thomas Arthur Williamson is remembered by the people of White Hills. The names of the local lads who sacrificed their lives and those that were fortunate to return from the Great War are shown on the embossed copper plaques on the White Hills Arch of Triumph, at the entrance to the Botanic Gardens.