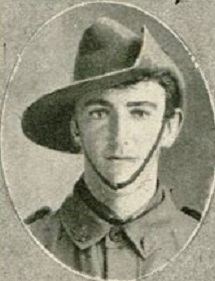

MCCALLA, William Joseph

| Service Number: | 5622 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | Not yet discovered |

| Last Rank: | Private |

| Last Unit: | 25th Infantry Battalion |

| Born: | St George, Queensland, Australia, date not yet discovered |

| Home Town: | Howard, Fraser Coast, Queensland |

| Schooling: | Not yet discovered |

| Occupation: | Coal Miner |

| Died: | Killed in Action, Mont St Quentin, France, 2 September 1918, age not yet discovered |

| Cemetery: |

No known grave - "Known Unto God" |

| Memorials: | Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour, Howard War Memorial, Shire of Howard Roll of Honour, Villers-Bretonneux Memorial |

World War 1 Service

| 7 Sep 1916: | Involvement Private, 5622, 25th Infantry Battalion, --- :embarkation_roll: roll_number: '15' embarkation_place: Brisbane embarkation_ship: HMAT Clan McGillivray embarkation_ship_number: A46 public_note: '' | |

|---|---|---|

| 7 Sep 1916: | Embarked Private, 5622, 25th Infantry Battalion, HMAT Clan McGillivray, Brisbane |

Help us honour William Joseph McCalla's service by contributing information, stories, and images so that they can be preserved for future generations.

Add my storyBiography contributed by Ian Lang

#5622 William Joseph McCALLA 25th Battalion

William McCalla was born in St George to Samuel and Bella McCalla. By the time William enlisted, his father had died and his mother had remarried a Mr McKenna. William presented himself for enlistment at the Brisbane recruiting depot in Adelaide Street on 21st February 1916. He gave his age as 18 years and nine months, stated his occupation as miner and named his mother Bella McKenna of Howard as his next of kin.

At Enoggera, William was allocated as a reinforcement for the 25th Battalion, and after some initial training embarked on the “Clan McGillivray” at Pinkenba Wharf, arriving in Plymouth on 2nd November 1916. William spent the next two months at Wareham Depot before being admitted to Bulford War Hospital with venereal disease. He spent a total of 53 days in the VD wards and during that time received no pay as venereal disease was considered self-inflicted. William was discharged to duty on 12th March 1917.

Two weeks after being returned to duty, William was charged with being absent from a parade and was fined two days pay. This charge, though only minor was to begin an escalating series of disciplinary offences. On 27th April, William was charged with being Absent Without Leave for a period of 30 hours. He received as punishment 7 days Field Punishment #2 (in which the offender had to be placed in manacles for two hours a day) and was fined 4 pounds and 15 shillings, the equivalent of 19 day’s pay.

In June of 1917, as the first of the battles in Belgium began at Messines, William was transferred to the Base Depot at Rollestone before being shipped to the continent from Southampton. He was finally taken on strength by the 25th Battalion on 9th August. The 25th Battalion was at that time in camp in the rear areas to the west of Ypres in Belgium, preparing to go into action in the battle of Menin Road the following month.

William did not stay long with his unit. Five days after he arrived in the battalion lines, he reported sick. At first it was assumed that William had contracted another case of VD and he was sent to the VD Hospital at Rouen on the French coast where he spent three months before it was determined that his affliction was unable to be definitively diagnosed. Consequently William was sent back to England where spent time in the barracks at Hurdcott during December and January. On 15th February 1918, William was listed as AWL, having failed to return from a period of leave. He was arrested in London by the Military Police and returned to Hurdcott where he received a sentence of three days FP#2 and lost 8 days pay. Further investigations into William’s time in London resulted in him being charged with stealing and receiving stolen goods. This was a serious charge and William was placed in detention awaiting a District Court Martial.

At the DCM, William was found guilty and sentenced to 6 months imprisonment with hard labour. A fortnight later he faced a second DCM charged with escaping custody which earned him a sentence of 90 days in prison. The sentences were to run concurrently and William was sent off in manacles to Lewes prison on 2nd April, a grim Victorian gaol run by the British Military, to serve out his 6 months. While in prison, William turned 21.

While William had been in Prison, the AIF was struggling to maintain viability due to a shortage of reinforcements. The first half of 1918 had seen desperate struggles by the AIF in France holding and then turning a massive German offensive. On 8th August near Amiens, the British forces which consisted of five divisions of Australians and three divisions of Canadians, supported by two British divisions on the flanks drove through the German lines into clear country beyond. All of a sudden, the war had changed into a mobile advance with the enemy scrambling to consolidate. The British General Douglas Haig told his Australian Corps Commander John Monash that he should press home his advantage, even at the cost of casualties. Monash was sure he could gain a decisive advantage in France but to do it he needed every available man who was capable of holding a rifle.

Five days after the success at Amiens, William was discharged from Lewes with the remainder of his sentence remitted. The next day he was on a ferry at Folkstone headed for France. On 20th August he walked into the 25th Battalion lines. He may not at that time have even been issued with a rifle.

The 25th, part of the 7th brigade of the 2nd Division AIF had performed well in the Amiens battle and continued to push eastward harassing the enemy and taking prisoners. By the end of August, the AIF had reached the point along the Somme where the river turned south in front of the fortress town of Peronne. Overlooking Peronne was a small but heavily defended hill, Mont St Quentin.

If Monash was to take and hold Peronne, he would need to take Mont St Quentin as well. An attack by other Australian units had briefly held the summit of the Mont on the 1st September before being driven off. The original plan was for three Brigades from the 2nd Division to assault the summit of Mont St Quentin on 3rd September but the plan changed. At 10:30 on the night of 1st, A divisional conference was called where Brigade and Battalion Commanders were informed that the assault was to be brought forward with Zero Hour being 5:30 am on 2nd September; 7 hours away. There was no time for reconnaissance and the plan was therefore quite simple but quite audacious. The artillery barrage crashed down at 5:30 am and the men of the 25th Battalion, thee companies abreast began to move out from their positions to the north of the Mont and proceed along the Bouchevesnes Spur. It was not long before the 25th began to be hit by heavy enemy artillery which consisted of high explosive and mustard gas. As the platoons moved out of the Mt St Quentin wood they were able to begin engaging with the numerous machine gun posts by sending small parties around both sides of the emplacement. This was a technique which the AIF had been using since the Ypres campaigns in 1917 and they were well versed in its application. Unfortunately for William this battle, which the Brigade Commander called the toughest the brigade had faced, was his baptism of fire. He has only been out of prison less than a month and had been with his battalion for 13 days.

William’s file simply states that he was killed in action on 2nd September. He was 21 years old. There is no Red Cross report into his death. In all likelihood, William was a victim of artillery fire as there is no mention of a burial. There is no mention of William’s remains being recovered, either just after the battle or at the end of the war when teams from the Imperial War Graves Commission scoured the battlefields searching for fallen soldiers. The location of William’s remains were never found. He is among over 10,000 Australians who lost their lives in France between 1916 and 1918 and have no known grave.

The action by the 2nd Division at Mont St Quentin was the most significant and important engagement by the division in the entire war. When sites were being chosen for divisional memorials in France and Belgium, Mont St Quentin was the site chosen for the 2nd Division Memorial. The memorial originally depicted a digger leaning over a stricken eagle with his bayonet at the bird’s throat. Needless to say, the memorial did not survive the German occupation 1940 – 44. The current memorial shows the digger in a relaxed pose in full battle kit looking off into the distance.

In the 1930’s the Australian Government finally constructed the Australian National Memorial on a wind swept hill near the village of Villers Bretonneux. The names of the 10,000 or so fallen soldiers from the war are commemorated on the stone tablets there. William McCalla’s name and battalion appears on walls of the memorial.

When war medals were being distributed, William’s mother Bella McKenna signed for the medals and memorial plaque at her home in Paddington, Brisbane.