PRING, David Cameron

| Service Number: | 4718653 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | Not yet discovered |

| Last Rank: | Gunner |

| Last Unit: | 161 (Independent) Reconnaissance Flight |

| Born: | Adelaide, South Australia, 15 April 1946 |

| Home Town: | Not yet discovered |

| Schooling: | Sacred Heart College & Henley High School, South Australia |

| Occupation: | Builder |

| Died: | 20 August 2016, aged 70 years, cause of death not yet discovered, place of death not yet discovered |

| Cemetery: | Not yet discovered |

| Memorials: | Somerton Park Sacred Heart College "Old Scholars Who Served" Post WW2 Honour Board |

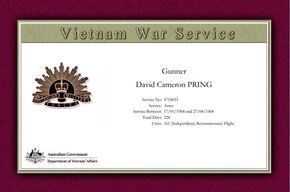

Vietnam War Service

| 17 Jan 1968: | Involvement Australian Army (Post WW2), Gunner, 4718653, 161 (Independent) Reconnaissance Flight |

|---|

MEMORIES OF VIETNAM

Gunner David Pring 4718653

161 Reconnaissance Flight

Nui Dat, South Vietnam. 1968

ARRIVING

It is February 2nd 1968, a summer Saturday for most Australians. Below deck on the aircraft carrier HMAS Sydney, it is our first day in Vietnam. During the night as we sleep, the ageing troop ship sails quietly into Vung Tau Harbor, after seventeen days at sea. Before dawn we are woken, dress and collect our belongings. With feelings of anticipation and relief that the long journey is over, we assemble and prepare to leave.

I am with the first group elevated onto the flight deck. Briefly surrounded in darkness by steel walls, then emerging to a panorama of hues, shadows and distant lights. A twin rotor Chinook helicopter, looking like a bloated grasshopper, waits to carry us off the ship, as the calm of the tropical dawn is disturbed by the thudding of nearby choppers. Night time favours the enemy, now South Vietnam is being taken back by the Americans and their allies.

The sound of one chopper increases as an Iroquois gunship descends onto the deck, metres from where we stand. Armed soldiers emerge, moving with purpose and authority. This is my first contact with the Americans and I watch in awe, as the noise and spotlights increase the drama. Because of the urgency, we realise this is not planned. After a brief conference, the Americans leave and we are directed to the waiting Chinook.

GETTING THERE

On Tuesday 16th of January, we depart from Cockatoo Island naval base in Sydney Harbor. We are a mixed group of replacements from camps around Australia and I'm an artillery gunner, posted to 161 Independent Reconnaissance Flight. Friends and family of local troops give us a small but noisy farewell, while colored streamers fly from ship to shore, breaking as we leave the wharf. Our mid-morning departure attracts little attention from the city workers, who are mostly unconcerned by the Asian war.

The sky is overcast as we sail across the harbor and left alone with my thoughts, I know it will be months before I can return. I am a conscript who had ten months left in the army and a choice between Vietnam, or boredom in Australia. Four weeks of jungle training, one week of leave and I am away. The benefits are

worthwhile and the risks acceptable. I remind myself of this, as we leave the secure harbor and plough through the narrow heads, into the rolling waves of the Pacific Ocean. Insulated by distance, we sail north to an uncertain future.

The sleeping quarters below deck are basic and crowded. To our amusement, we are required to sleep in hammocks, suspended from the ceiling. Further north, the temperature becomes uncomfortable and I search for better quarters. With some others, I choose the bow section, beneath the flight deck, where the anchor chains are stored. It is shaded from the sun and open on the side to cooling breezes. Sailors call it the 'focsal', which is short for forecastle.

Two days out of Sydney, I remember my dad's birthday and ask a sailor if I can send a message to Adelaide. Without hesitation, he leads me up to the bridge and into the radio room, where a telegram is sent immediately. This informal response by the sailors is well received.

Off Queensland, we sail into heavy seas. I wake to a loud hissing noise and discover the deck below my hammock covered with water. The anchor chain funnel allows the sea to surge upwards, as we push through the waves and flood across the deck. In the dim lighting, the others appear to be asleep and unaware of the worsening conditions. So, with only a steel cable between me and the black sea, I decide to stay put and return to a restless sleep.

By morning, huge waves crash around the flight deck, normally metres above sea level and I consider moving my bed to the rear of a truck, stored on deck. However, the rolling motion of the ship, makes me appreciate why sailors are issued with hammocks. It is still hot below deck, so with water washing over my feet, I decide to secure my hammock and ride out the storm in the bow.

Many soldiers become sea sick. For one unfortunate, the sight of his breakfast plate with bacon and eggs, sliding over the laminated table, is enough to send him running for the rails.

During the storm, I am called to the sick bay. It seems there is no record of my immunisation. Protest is futile and over two days I am given more injections. Because the ship is rolling, the medic decides we will stand in the narrow corridor and use the walls for support. Passing sailors are amused by my discomfort.

Sailing into the tropics, life becomes more relaxed. Lectures and games help pass the time, but as the humidity increases and soldiers wander, organisation suffers. Men from different units mix and new friendships are formed. I meet Bob, an engineer who is also with 161 unit as a fireman, Dennis, a caterer and Peter, a fellow gunner. In civilian life they were a fireman, cook and woolclasser. I was a draftsman.

Rifle practice is fun. Balloons are released from the stern and we enjoy firing at them, as they bob in the ship's wake. Soon we run out of bullets.

Reaching New Guinea, we sail close to shore and view the imposing landscape, made famous by a previous generation of Australian soldiers. A mass of green curving up from the sea and disappearing into a shroud of grey clouds. The next morning we arrive at Mannus Island, a world war harbor, north of New Guinea. The ship anchors close to shore, where dense jungle hides any sign of life. The emerald green of the deep water and the jungle green is a relief from the blue and grey we are used to, but the humidity is intense. A landing craft is launched to assist the carrier with refueling and soon natives appear in dug out canoes, paddling to the ship with fruit and souveniers. I buy a carving and a coconut, however the novelty quickly wears off and I am pleased when we leave that afternoon.

At sea we are joined by the Australian destroyer HMAS Brisbane, which positions itself off our stern. The carrier's helicopter begins to patrol nearby and rumors circulate about a foreign submarine. Twice the destroyer comes within metres of the carrier, as both ships travel at speed. The first time to refuel and then to transfer sailors on a 'flying fox'. These events are interesting and probably dangerous for the sailors. The destroyer stays for a few days, then moves on.

Crossing the equator, we celebrate on the flight deck. One by one, volunteers are seated above a dunking pool and have cream cake squashed in their face, as they are dropped into the water. Every soldier receives a certificate from 'King Neptune'.

Sailing northwest between Borneo and the Philippines, we pass many small islands. Some are no larger than tennis courts and remind me of comic strips with marooned sailors. The larger islands are postcard perfect, but none are occupied. On a still night, I notice the lights of a ship heading the other way.

Apart from the destroyer, it is the only ship I have seen on the voyage.

Passing a group of sailors, I notice one is dressed in a wet suit and life jacket. Suddenly he jumps overboard and the other sailors move into action. One sets off the alarm, others prepare a rubber dinghy and outboard motor. Some change into wet suits. The ship is still moving and minutes have passed, so I climb up to the flight deck for a better view. The ship is now slowing and the dinghy is in the water. In the distance, I can just see the sailor bobbing between the swells. The ship finally stops as the dinghy reaches the 'man overboard'. He must be crazy.

'Netball' with quoits is well attended. A quoit replaces the ball and a soldier holding a broom handle is the goal.

Eventually the quoits are lost overboard and another activity ends. Volleyball in the elevator shaft gathers spectators, but the heat off the steel walls discourages players.

The traditional rum ration is replaced by a beer quota of one large can per person, per day. After a day in the tropics, this is welcomed and usually there are enough non drinkers, ready to sell their cans to those who enjoy another. Relaxing on deck with mates and a cold beer, as the sun sets on a glass smooth ocean, is most enjoyable. After the evening meal, movies are shown below deck in the flight hanger. At first they are popular, but as the humidity increases, and the quality decreases, so does the enthusiasm. Gradually we are being overwhelmed by boredom.

The voyage from Australia to Vietnam is about twelve days. On this trip the carrier detours to Sattahip, a port in Thailand. Massive construction work is progressing and the workers show little interest in our presence. Most of the equipment on deck is unloaded, along with a group of signallers, who then drive away. We are left to guess their intentions. After two weeks at sea, we regret that we cannot leave the ship, if only to say we landed in Thailand.

The next port is Vung Tau, South Vietnam. At sea a U.S. plane swoops over the ship, leaving with a friendly roll of its wings. A reminder the war is not far away. We know it is the last night at sea, when we must return to our original quarters.

DAY ONE

Sunlight breaches the hilltops surrounding Vung Tau, as we board the chopper. The rotors accelerate and we leave the ship, climbing steeply, while the rear cargo door remains open.

Several hundred metres high, we stare down at the grey carrier which now appears tiny against the blue ocean and still the door remains open. Although we are strapped to our seats, gravity pulls us towards the opening. Finally, we shout abuse at the chopper crew and the door is closed. Expecting a flight to Nui Dat, we are surprised when the chopper descends.

Minutes later we land in a swirl of dust. Waved off the aircraft, we are left confused on the tarmac of the U.S. airbase at Vung Tau, where a soldier directs us to a staging post and tells us to wait. This is our first contact with land, since leaving Australia. It seems the dawn confusion was due to a mortar attack near Nui Dat and it was then decided to send us ashore in landing craft, but one chopper had already arrived.

After weeks at sea, the heat of the land is oppressive. By now, breakfast is over and it is too early for lunch, so we scrounge bread and coffee, then wait for the others. It is a strange start to our tour of duty. The trucks arrive and deposit those going to Nui Dat, while those staying in Vung Tau continue to their units. Soon lunch is provided, but it will be some time before a plane is available, as aircraft are in demand.

While we were at sea, the Tet offensive by Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces began. The enemy has attacked Tan San Nhut airport and Saigon, where they briefly occupy the U.S. Embassy. Intense street fighting continues in Hue, the imperial city of Vietnam.

To pass time, Peter, Bob and I decide to explore the air base. There is little shade and the bitumen is hot under our feet.

Passing a black American Sargeant, I ask where we can get a beer and he points to a stone hut, telling us to go inside. On opening the door, we are met by a rush of cold air. The room is dimly lit and the scarlet walls are decorated with framed playboy centrefolds. Tables and chairs are grouped around the floor and in one corner is a candy striped bar with a canopy, creating a French theme. Impressed, we approach the counter and order beers, delighted to receive frozen pewter mugs and cans of 'Budweizer' caked in ice. Enjoying the atmosphere, we celebrate our arrival with several more, before relunctantly deciding to leave. stunned by the heat outside, we return to the staging post, part drunk and drowsy and slump in the shade for a short wait, before the plane arrives.

A fixed wing Caribou transport plane carries us over rice fields and scrub and soon we are circling above Nui Dat. Apart from the bitumen air strip, the base camp is concealed by trees and its size is deceptive from the air. It is late afternoon as we land and the sun is low on the horizon and losing heat. It has taken nine hours to travel thirty kilometres.

Saying farewell to Peter, Bob and I walk the short distance to the aviation unit. The duty sargeant welcomes us, telling me to store my gear in the 'guest' tent, as I will be moving in the morning. We are invited to the canteen for a beer, where I discover Saturday night is a reason to relax and socialise. More beer, no food, Vietnam is looking good. In the darkness, I stroll back to the tent and fall into a deep sleep.

During the night, my sleep is shattered by loud explosions. I wake terrified and roll off the stretcher, onto the floor. I can't remember where I am. The noise stops and I listen for shouting, but there is none. Too scared, confused, or drunk to move, I grab my pillow and lie on the floor, realising I don't have a rifle. Again the sharp explosions and the tent shakes. Quiet returns, so I crawl onto the stretcher and fall asleep.

I wake to a perfect tropical day. Dawn sunlight filters through the trees and the damp air is still cool from the night. Alone in the tent, no one has disturbed me. After a wash and shave, I head for the mess hut, where I learn the explosions from last night, were our guns firing out. They were firing directly over us, increasing the noise and creating shock waves. I am told the guns fire day and night, but I will get used to it. Day One in Vietnam has been a memorable experience.

After a good meal, I report to the administration hut. The duty sargeant is a friendly man, who introduces me to the commanding officer. He is a pilot and wears an infantry badge on his beret, because 161 Flight does not have a unit insignia. Looking uncomfortable behind the desk, he welcomes me, briefly describes my duties and refers me back to the sargeant. My job is to control artillery and aircraft from Task Force Headquarters.

THE BASE CAMP

We leave the Flight and drive in a dusty Land Rover, along dusty tracks, to my new quarters. It is the dry season and the camp has a look of fatigue. Passing vehicles cover trees and tents with dust. Stormwater drains are filled with dead weeds and rusted barbed wire hangs on crooked stakes. Temporary has become permanent and priorities change in a war zone.

Nui Dat is a fortress home to Australian infantry, artillery, armour, engineers, aviation and support groups. It is also host to a U.S. artillery battery called the 'Heavyweights'. The perimeter is surrounded by land mines, barbed wire, trenches and bunkers. Set in a rubber plantation, the trees provide concealment, protection and comfort. The bitumen airstrip called 'Luscombe Field', runs from the centre and projects into the scrub. Nui means hill, and Nui Dat is the feature of the camp.

It is occupied by the elite Special Air Service and offers a vantage point over the flat countryside. I am told several Americans died, taking it from the Viet Cong. To the west are the Nui Thi Vais. Within range of the guns, the ragged mountains create attractive sunsets and a refuge for 'Charlie'.

The camp is divided into self contained units. Administration and mess huts are prefabricated steel sheds with concrete floors. The sleeping quarters are raised timber floors, surrounded by waist high sandbags. Canvas roofing overlaps the sandbags, leaving a gap for ventilation. Each unit has a canteen, or 'boozer', which is the social centre for those not on duty, or returning from operations. Scattered among the tents are weapon pits, shoulder deep and big enough for three men. They offer shelter in case of attack and remind me of open graves.

Certainly a trap for careless, or drunken soldiers at night.

We turn into a compound, stopping at three tents occupied by the Flight, where the sargeant introduces me to the corporal in charge and leaves. Des is friendly and relieved to see me. The other corporal is at a support base, one soldier is working and the other asleep. He tells me the required number is five, but one is about to leave.

Inside my tent home are three stretchers with mosquito nets. There is little floor space and belongings are stored under them. A previous occupant has planted a banana tree near the entrance, which gives the tent character and makes it easy to find amongst the others. Every surface is covered in dust. The second tent is occupied by the two corporals and since there is more room, it is used for meetings and relaxation. The third belongs to Colin, the warrant officer in charge. He spends most of his time at the Flight, but allows us to use his Land Rover.

Showers are available in a small shed with a header tank and combustion boiler. The toilets are a communal 'long drop' inside a shed, ventilated with fly screens. Near our tent is a clay sewer pipe, partly sunk into the ground. This is our urinal.

Nearby is the mess hut, 'theatre' and canteen. Next to the mess is a sign, ordering that all weapons remain outside. It reminds me of a wild west movie. The menu is bacon, eggs, chicken and steak, with canned fruit for desert. The Americans have their own refrigeration ship and sometimes ice cream is available. Our 'theatre' is a white screen, the size of a double bed sheet. A shelter on posts is the projection room. On it, is a roughly painted sign with the words, 'Her Majesty's Theatre Nui Dat'.

Several benches are placed between shelter and screen. The canteen has standing room for about forty soldiers and the walls on three sides stop at waist height for ventilation. In one corner is a large freezer, serving as a bar and in the centre is a worn snooker table. Cans of beer and soft drink are cheap.

Next to the airfield is the Australian postal exchange store. It is a shed where luxury goods are sold duty free. Electrical items and expensive alcohol are sold out on arrival, while cigarettes and toiletries are usually available on request.

Task Force Headquarters is a collection of steel huts and we have a small room next to the artillery command post. There is enough space for a desk, two chairs and a filing cabinet. Above the desk is a radio set and a large map of Phuc Tuoy province, covered in clear plastic. A marker pen, protractor and ruler are used to plot the distance and direction of artillery. A small fan sits next to the radio and steel louvres on the side walls allow cross ventilation. Outside, the rubber trees provide a relaxing atmosphere and welcome shade from the afternoon heat.

Everything is covered with dust. The next hut is occupied by the

U.S. Air Force, who control air strikes in the province and lend us their jeep.

The American 'Heavyweights' are 200 millimetre diameter cannons, propelled on tracks, like huge army tanks. They have a firing range of 20 kilometres, which is double that of our guns. The U.S. gunners have their own facilities, including a convenient barber shop, complete with candy stripe poles.

I inherit a rifle and a deck chair and spend a quiet evening getting to know my workmates and the war. I discover that little happens in the province without their knowing. Feeling weary, I go to bed early, forgetting the U.S. artillery is nearby. During the night I am reminded why they are called 'Heavyweights', as loud explosions and tremors keep waking me. This time I am annoyed, not scared, but I can't believe I will get used to them. In the moonlight I peer toward my tentmate. He is fast asleep.

THE JOB

My first week is spent training with Dave, who is naturally friendly, but especially now, because his time is 'short'. I had been concerned about formal radio procedure, but discover there is none. The problem is trying to understand what pilots are saying, because of static and accents. I have become part of a group of soldiers who provide information and advice to pilots, trying to avoid artillery and air strikes. This is very demanding, as pilots require quick responses for angles, heights and distances. Often they prefer the operator to recommend a safe passage, which is difficult when many pilots navigate by following main roads. Then it is necessary to direct them under the shells, or behind the guns. Our call sign is 'Nui Dat Arty'.

The Americans I speak to are casual, cheerful and courteous, which is unexpected, considering the nature of their work. They also like to abbreviate. Viet Cong becomes 'V.C.' which is 'Victor Charlie' in the army alphabet and then 'Charlie'. The South Vietnamese army has the initials A.R.V.N. and are called 'Arven' by their allies. Postal exchange is 'P.X.' and Military Pay Currency is 'M.P.C.'. The Demilitarised Zone between North and South Vietnam becomes the 'D.M.Zee'. Unlike the United States, the American forces use metric measurements and kilometre becomes 'klick'.

During a day shift, we receive a visit from our commanding officer. He looks imposing with his blue beret, holstered pistol and hands on hips. He is polite and caring and is the only officer I have met, who introduces himself using his first name.

When pilots enter the province, they request air clearance and notify us of their departure. Many forget! A log book is used to record all enquiries and except for emergencies, artillery cannot fire without clearance. The controller must warn all pilots, which takes time and often frustrates the artillery command post.

There are three shifts, day, evening and night, running continuously, seven days each week. The quiet night shift extends for nine hours allowing shorter, but busy day shifts. Rosters are rotated on Sunday and when work is finished, we are usually left alone. This is partly due to the lack of control by 161 Flight and Headquarters presuming we are controlled by the Flight.

The day shift is busiest, with many aircraft needing instructions. Often we have guns firing from three locations. The day passes quickly and after work there is time for a cool shower and a cold beer before dinner. Then usually an outdoor movie in the cool of the night. Most are 'B' grade, or re runs, but 'spaghetti' westerns are popular. This is followed by a normal nights sleep and as predicted, the guns have become a minor instrusion.

Night shift is worse for me. I find it difficult to sleep during the day because of the heat, noise and sunlight. Usually I wake after four hours soaked in sweat. After six nights, I am exhausted and irritable, eventually falling into a deep sleep on the Sunday.

The afternoon shift is busy until dark, then quiet. The rescue chopper called 'Dust Off', signals the end of the day as it returns to Vung Tau. Its arrival at sunrise, the start of another. Getting to bed around midnight, still allows a good sleep and some free time until the next shift. This is when I can leave the camp, or visit other units. I promise myself a trip on the 'Dust Off', for a night in Vung Tau.

Access to the Land Rover makes short trips to Baria, or VunG Tau possible. The roads are color coded red, yellow, or green, according to enemy activity. Soon after the Tet offensive, they are rarely green, which confines us to the camp. Dawn patrols discover land mines laid the previous night and sometimes they don't. Before sunset, I enjoy driving to the Flight to collect the mail. I prefer the jeep, which is more fun than the heavy Land Rover and follow the dirt road that detours into the scrub, around the air strip. At dusk there is little traffic, so I can speed. The duty sargeant is always friendly, but the other soldiers wonder who I am.

On one visit to Baria, we stop for a funeral procession. Gradually the Land Rover is surrounded by mourners dressed in their best clothing. We look out of place in our dusty vehicle, with rifles and crumpled greens, but the Vietnamese seem indifferent to our intrusion. I think how easy it would be for Charlie to drop a grenade into the Land Rover and walk away.

The offensive strains all resources and like every unit we are understaffed. Four men are available when five are needed and then we are reduced to three when replacements arrive late, or someone is on leave. The two required for day shift becomes one. During the day, the duty controller should be relieved for meals, but often we work through, to avoid disturbing the others.

Despite the long hours and on site training, the small unit operates efficiently.

Most B52 bomber strikes are at night. The U.S. air force requests air clearance, lasting several hours, but never mention why. Just a grid reference and a five kilometre exclusion zone. Looking at the circle drawn on the map, I wonder at the destruction ahead. The planes fly from Guam, or bases in Thailand and there is no noise, they are too high. Nearby strikes are like a tropical storm, flash lightning and rolling thunder. Pity the poor buggers in it!

In April the rains arrive and the dust becomes mud. Each afternoon the storm clouds gather and it pours for around two hours, flooding drains and weapon pits, then clears. But the nights are cooler.

At the end of a night duty, as the sun is rising, I receive a request for flight clearance from an American pilot. It is Sunday morning, no guns are firing and clearance is given.

Suddenly, two Phantom jets scream across the tree tops and return seconds later, blasting the camp with noise. By now all of Nui Dat must be awake. Leaving work, I pass the Brigadier's quarters. He is standing outside in his shorts, waving his fist in the air and demanding answers. Avoiding eye contact, I try to walk casually back to my tent.

One afternoon, I am required to collect four Americans from 'Kangaroo' chopper pad. They arrive in two new Cobra gunships, circling like sharks before landing. The pilots wear red baseball caps and their leader has the word 'Boss' above his Major's insignia. I am impressed. A chopper has crashed, possibly brought down by artillery fire and the pilot is killed. Our logbook shows his passage from Saigon to Vung Tau, but there is no record of the return flight. Again, no conclusions are offered.

We are notified that the Prime Minister, John Gorton, is visiting Nui Dat. He was a spitfire pilot during the world war and is interested in seeing the Flight. The c.o. has requested one of us be present when he arrives and I am available. It is a casual gathering and we form into line to meet the Prime Minister. The

c.o. warns that if he forgets our names, we must respond to the name he invents. I become one of those introduced with a false name.

Occasionally Australian entertainers arrive at the camp. Near the air strip is 'Luscombe Bowl', a small stage facing up hill, where a few hundred soldiers gather. We enjoy the music, the jokes and especially the female singers in their brightly colored mini dresses. They offer a welcome break from the war and remind us of home.

Since my arrival, two soldiers have left and one has arrived. Bruce is a conscripted university student from Queensland, who was offered Vietnam, or a spell in the stockade. He amuses me with his dry humor and disregard for anything regimental. His spare time is spent scheming of ways to make money and avoid conforming to army discipline. The Army in its wisdom, may have concluded that 161 Flight was the best place for him.

Two soldiers run past my tent with a mosquito net, made into a catcher. They are chasing butterflies! The camp is sprayed with mosquito poison by Caribou planes and we presume it is safe, because the plants and butterflies remain. There are few mossies.

The Americans call any place outside of Vietnam the 'World', implying Vietnam is somewhere else. Mail from family and friends is the fragile link with home. Most soldiers receive words of love and encouragement, but some letters deliver bad news which cannot be easily resolved, reminding us we are stuck here. My mother is a creative writer, who sends letters regularly, while I struggle to finish a page. She also sends the 'Sunday Mail' newspaper, which creates a queue of fellow South Australians, wanting news of their home state.

Off duty, we are sometimes called on to assist in aircraft. One morning, an Iroquois chopper collects me from 'Kangaroo' pad, for a leaflet drop. We fly over twisting rivers and dense jungle that conceals the enemy and bomb craters that leave the landscape looking like the surface of the moon. The chopper doors have been removed, so I tread carefully, as hundreds of leaflets are tossed out. They offer the enemy safe conduct through allied lines and I keep one as a souvenier. It is a convenient way to see the province.

The U.S. armed forces radio is a huge means of commmunication and entertainment. Operating like a commercial station, it caters for all musical tastes, with health education, enemy warnings and holiday destinations, promoted as clever commercials. News breaks and sport updates are frequent, while messages from home, with musical requests, offer support. Every effort is made to comfort U.S. soldiers. We Aussies share the American experience, including new rock bands, soul music and sadly, the killing of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King.

The siege of Khe Sahn by the enemy, near the boundary with North Vietnam, becomes a military and political struggle which is reported daily, like a sporting event.

Under the circumstances, any propaganda is subtle. In contrast there is 'Hanoi Hannah' on another frequency. Her broadcast is so biased that it defies belief. Even 161 Flight is mentioned. I am surprised they know we exist. The Aussies also have a regular program which is quaint by U.S. standards, but keeps us in touch with home. Soldiers with larger transistor radios, can also receive Radio Australia.

A benefit of our work is the lack of parades, roll calls and inspections. The corporals lead by example, but tolerate lesser standards. Shaving before work is expected, but cold water shaving is painful. The boiler is fired up at sunrise and quickly empties while I am sleeping, or working. The only regular supply is from the mess hot water urn, but asking would invite a negative response. After a meal, I discreetly fill my mug with boiling water and return to the tent. Bruce who shaves less often, laughs at my antics.

R. AND R.

Five days rest and recreation in an Asian city, is the bonus of Vietnam. I decide to go early, just in case and choose Hong Kong partly because I have friends there. A Caribou arrives from Vung Tau with other travellers, collects our small group and flies to Saigon. On board is an old friend from primary school. We are surprised to meet in this place, so far from home. Jeff crews on a Navy helicopter and is going to Bangkok. Split into groups for the next flight, I make friends with a rifleman from three battalion. In civilian life, Ian is a teacher from Melbourne.

Tan San Nhut airport is one of the busiest in the world. Chartered commercial jets and military planes constantly arrive and leave with troops and supplies. A huge 'Starlifter" cargo plane taxies past, while Phantom fighter jets leave on combat missions. One has a 'flame out' metres in the air and thumps back to the tarmac. The burnt out wreck of a transport plane and ruined buildings, are the only evidence of the recent offensive. We are restricted to the base for several hours, waiting for our next flight, which is frustrating because the city is nearby and it is our first day of leave. We visit the souvenier shop and then find a crowded bar, where we are entertained by a Vietnamese rock band, eventually boarding a Pan American jet for Hong Kong.

Arriving late in the afternoon, we decide to have a relaxing night and meet the next day. Fortunately, our respective accommodation is only short walk apart. That evening, I have the luxury of a steaming hot bath, my first hot wash in three months. My Asian hosts believe Australians drink lots of beer and to my embarrassment, their fridge is stacked with bottles. Near midnight, I am taken to the Chinese district for a meal. The city is still teeming with activity and it is two hours before we return to the apartment. After another cold beer, I finally retire to the comfort of clean sheets and a spring mattress. The next four days are spent touring, shopping, dining and relaxing, always aware we must go back.

Returning to Nui Dat, I decide to walk back to the tent. I am wearing dress uniform and carry new golf clubs. A convoy of trucks passes, taking infantry into the scrub. From the last truck, a soldier leans out and yells at me, 'War is Hell'.

BACK TO WORK

The battle at fire support base 'Coral' increases tension and drains resources from the camp. I am required there to assist aircraft, but the corporal argues we don't have the numbers.

The Flight decides I am needed as an observer in a fixed wing Cessna, armed with four rockets. Leaving 'Luscombe' we fly over a plantation, where the pilot circles the homestead, until a pretty Vietnamese woman emerges and waves. This appears to be a regular event. We then fly above thick jungle, close to the tree tops and soon locate a roughly made footbridge over a creek. The pilot rolls the plane and dives toward the bridge. Already my stomach is uneasy and this does not help.

The first rocket misses the target, exploding nearby, so the pilot executes another sickening turn and heads down again. As he fires the second rocket, I notice puffs of smoke from the trees. Charlie is firing back! I yell at the pilot, who curses and makes a quick exit, much to my relief. It is over before I can retrieve my rifle from behind the seat and unfortunately the bridge remains intact. We then search for a hut hidden in the jungle while I lean out of the window holding a smoke grenade, to drop on the target. In my other hand is a paper bag, in case I vomit. After several futile loops, we abandon the search. I drop the cannister into a field and watch the bright red smoke, drift across the green surface.

On the way home we fly into an air strike. The explosions are in front of us, but is no sign of the jets and at their speed they cannot avoid us. The pilot curses, because he has not been warned and detours. I regret our lack of success, but value the experience.

Soon after, the soldier behind the desk, the officer who called himself George and forgot my name, the pilot I spoke to on the radio, is shot down and killed. I am stunned.

Weeks pass and my life becomes more predictable, work, tent, mess. I persevere because I am suited for the job and it will be over in a few months. I never thought I would tire of steak and chicken. For variety the cook swaps lunch and dinner. I crave pastry. Hot, crusty pies with sauce. Norm leaves and the new replacement arrives. Ron needs to be trained for several days, so we are down to three. I am conditioned to working most days, or nights and relaxation is a cold beer, a smoke and a game of cards. 'Dope' can be obtained, but most Australians prefer beer.

After dark, 'Charlie' attacks Baria, only a few kilometres away. Like watching a bushfire at home, we stand on the sandbags, as the night sky glows red, from the flares and fires of battle. By morning 'Charlie' has gone, but the destruction remains.

Pranksters detonate a smoke cannister in the communal long drop and two half dressed soldiers emerge in a cloud of blue smoke, covered in dye. Another day, I am standing at our urinal when a black snake slides past my feet. Frozen to the spot, I watch as it disappears into the weeds.

I welcome the odd visit from Peter, or Ian, but they find me working, or sleeping. I wish I could spend some time in the bush to break the routine. Des goes on leave for five days and I am left as acting corporal, or bombadier in artillery terms. There is no formal, or financial recognition.

Between shifts, Bruce and I arrange a trip to Vung Tau, intending to fly back in the afternoon. We explore the town and stop for lunch at a cafe. Across the street, a black american soldier is seated in jungle greens and helmet. On his lap is a Claymore mine. We are told he is absent from Khe Sahn, at the demilitarised zone and will detonate the mine if anyone interferes. The irony of Vietnam is that most people seem unconcerned by the drama.

We move on to the U.S. duty free shop on the airbase, to inspect the electrical goods and buy a Playboy magazine. I have promised a copy for a friend in Australia, where it is banned. The magazine is part of the war culture and valued by the diggers. I also buy the latest record album by Eric Burden and 'The Animals", to post home to another friend. Because of the psychadelic cover, I suspect it will not survive customs intact. At the control tower, we are told the air strip at Nui Dat has been shut down, due to rain. Because I am on night shift, we decide to hitch a ride.

Getting to the edge of town is easy. Army vehicles are heading in all directions and frequently stopping, but on the highway to Saigon, the traffic thins out and travels faster. Soon we are given a lift in a jeep, by a mean looking, but friendly, Vietnamese Colonel, who is driving to Baria. As it is near curfew, he offers us shelter for the night in the Vietnamese barracks at Baria, which we politely decline, preferring the safety of Nui Dat. He leaves us at the turn off to Hoa Long, where we are lucky to be collected by an Aussie truck driver, who is running late and arrive at the camp as the gates are closing for the night. After this, Bruce decides we should get our own jeep and rightly concludes the Americans would not miss one.

A drunken soldier, armed with a M60 machine gun, is told to leave the boozer, just as we enter. The rifle barrel lodges firmly in my stomach and while he shouts abuse at the group inside, I gently ease it aside. At night two drunken soldiers argue. One fires a rifle and the bullet hits my tent sandbag. Someone yells at them to keep the noise down and someone in charge tries to find the culprit. All is quiet, so I return to sleep.

It is pouring with rain and we are huddled in our tent avoiding the drips, as the wind shifts, so do we. Ron has a letter from his wife, in which she complains about her small flat and the boredom. He curses, stamps on the floor and waves his arms around the tent, asking us if she realises the conditions we live in. Bruce and I pretend we are insulted that he feels this way about our 'home', but are quietly pleased we are single. To relieve his frustration Ron strips naked, walks outside and stands in the rain. Bruce tosses him the soap and we all laugh.

In the early hours, I receive a call from a U.S. soldier who is changing frequencies on his radio and hears my accent. He tells me he is on a hilltop north of Saigon and I am surprised my radio can reach this far. I am concerned about security, but he is lonely and unsure that he wll survive the night. He talks openly, while I offer reserved comments. He is from the mid west of the U.S. and asks where I live in Australia. Most Americans have only heard of Sydney, so I tell him Adelaide is fifteen hundred kilometres south west. We wish each other good luck and sign off.

I feel like a fish in a bowl, around me soldiers are dying. Two gunners are killed by a Claymore mine, on their first night in Vietnam. Two infantry are gunned down at a checkpoint. Two pilots are shot down. A female Aussie entertainer and others are ambushed on the main highway from Saigon. Nearby the Americans and Vietnamese expel 'Charlie' from Baria, taking casualties.

Fire support base 'Coral' is almost a disaster, as the Australians withstand a concentrated enemy attack. Nearly thirty diggers are killed. Some die in accidents, but the enemy are losing far more. "Just do the job and get home", I remind myself.

GEITING SHORT

My time in Vietnam is getting short and I still have five days rest and convalescance leave in Vung Tau. When I arrive, the Australian R. and C. centre is almost empty. I have a two bed room to myself, a hot shower and two maids who fuss over me. The three storey building has a top floor patio, which gives views over the town and captures the sea breeze. A games room and bar on the same floor, make it a comfortable retreat after the 7.00pm curfew. The South Vietnamese police, called 'white mice' because of their uniform and size, are reputed to shoot first and question later. Nearby is a French cemetry, overgrown with weeds, suggesting that our presence in this country is only temporary.

On the perfect 'Back Beach' the Australians have a building called the 'Badcoe Club'. Yachts and surfboards are available and there is a bar upstairs. In the distance are the Long Hai mountains, a reminder that 'Charlie' also uses Vung Tau for R. and C. In the morning I swim, sail and relax on the beach. In the afternoon I shop and tour.

The Aussies are called 'Ook da Loi' by the Vietnamese who have trouble saying the word 'Australian'. Usually this is followed by 'Cheap Charlie' as we are less generous with our money than the Americans.

Military Pay Currency or 'M.P.C.' is issued by the Americans instead of U.S. dollars, as the 'greenback' is sought after by the Vietnamese, both South and North. The South Vietnamese currency called the 'Dong' has little value outside of the country and competes on the streets with M.P.C., which can be traded illegally for U.S. dollars. There is also a thriving black market in watches, electrical goods and alcohol, bought duty free at the P.X., or overseas on R. and R.

Hitching from the Badcoe Club, a truck stops and I climb aboard. The driver is a friendly black sargeant called Jones. He tells me he wouldn't stop for an American white man, but likes the Aussies. On his shirt is the 'Screaming Eagle' airborne insignia. I am impressed and tell him so. He offers me a spare shirt and we stop at his barracks, where the huts are segregated and whites are not welcome. He tells me I could be beaten, or knifed if I was alone, so I make a mental note not to lose him. He gives me his laundered shirt and drives me to the Centre. It is typical of the Americans.

On the last afternoon I visit the bars with Dennis, the cook from the carrier. My weekly pay is sixty dollars and a 'Saigon Tea' for two U.S. dollars, will buy the company only of a bar girl for some minutes. Fortunately we meet another Aussie who is engaged to a pregnant bar girl. As his guests, she gives us a bottle of good whiskey and we are set for the afternoon. The pretty Vietnamese bar girls of Vung Tau, have a song they use to intimidate the Aussie soldiers into spending their money. It is sung to the tune of 'This Old Man' -

"Oak da Loi, Cheap Charlie,

He no buy me Saigon Tea,

He no give me M.P.C.,

Oak da Loi, he cheap Charlie".

Later, we have drinks and dinner at the neglected Grand Hotel, where the Vietnamese staff try to maintain a previous elegance. Careless from alcohol, we overstay the curfew. Outside, I quickly farewell Dennis and seeking the shadows, run furtively to the Centre. The next morning I return to Nui Dat.

GOING HOME

Sixth intake national servicemen are due out of Vietnam by late August. Leaving is complicated. Forms, inventories, medicals, injections and endless tablets. September arrives and I am still working, with only twenty days left in the Army. I gratefully accept a pewter mug from the Flight, but the inscription states that I left Vietnam in August and the duty sargeant is amused by my concern at being forgotten. Another week passes and my replacement arrives. Finally, I receive a days notice to pack and depart.

My prized souveniers are the 'Airborne' shirt and a U.S. Army winter jacket, which I traded for my worn army boots, valued by the Americans. Getting the jacket meant walking back from the 'Heavyweights' barefoot in the mud, but I did not want to lose the chance.

Farewells are subdued, because one is working and another usually sleeping. There is also an element of guilt at leaving others behind. I shake hands with Bruce and my replacement and wish them good luck. Regretfully, I never took the 'Dust Off' for a night in Vung Tau and Bruce has not found his jeep.

The dirt roads are still damp and dust free, as Des drives me to 'Luscombe Field' in the Land Rover. The wet season is ending and Nui Dat is covered in rich green vegetation. While waiting, we switch on the radio and listen to the control frequency. Then, sighting the Hercules transport plane, we change to the Flight tower and listen to the landing instructions.

The pilot does not circle, as instructed, but drops quickly, almost clipping the trees as he lands and brakes hard. Passing the waiting soldiers, he leans from the window, giving a mock salute and thumbs up. It is the American style. They give a loud cheer, in appreciation of his theatrical landing, as I farewell Des and walk to the plane. It is a pleasant end to my tour of duty.

The Qantas flight from Saigon is brief, compared to the carrier voyage. The mood on board is quiet relief. I meet Bernie, a soldier from my platoon at Puckapunyal basic training camp. We shake hands and talk politely, but our experiences are not shared, and two years is a long time. He returns to his mates.

Sydney customs is chaotic. Excited relatives are waiting to welcome their men. I am uneasy because I have smuggled a Playboy magazine for my friend Ian, but customs wave me through. Those of us leaving for other cities, are taxied to a hotel for the night. We visit a night club, but no one feels like celebrating and after a few beers we return to the hotel.

The next morning I arrive at Adelaide airport, where it is my turn to be greeted by family and friends. After spending a day with my relieved parents, I report to Central Command. A clerk tells me it is pointless returning to a unit and a few rubber stamps later, I am standing at the bus stop, considering my future. I am twenty two years old. In the city I stop for a beer and then catch a bus home.

HET

Submitted 22 August 2025 by Rebecca Esteve