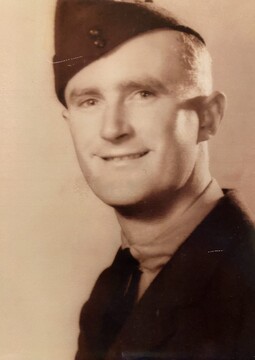

HEARD, Geoffrey Thomas

| Service Number: | 400708 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | 13 October 1940, Melbourne, Vic. |

| Last Rank: | Flying Officer |

| Last Unit: | No. 7 Squadron (RAF) |

| Born: | Willaura, New South Wales, Australia , 23 December 1915 |

| Home Town: | Willaura, Ararat, Victoria |

| Schooling: | Not yet discovered |

| Occupation: | Grazier |

| Died: | Flying Battle, Netherlands, 26 March 1942, aged 26 years |

| Cemetery: |

Gendringen Roman Catholic Cemetery, Gelderland, Netherlands Row A Grave 7 |

| Memorials: | Ararat Shire of Ararat WW2 Roll of Honour, Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour, International Bomber Command Centre Memorial, Numurkah Saluting Their Service Mural, Willaura War Memorial |

World War 2 Service

| 13 Oct 1940: | Enlisted Royal Australian Air Force, Flying Officer, 400708, Melbourne, Vic. | |

|---|---|---|

| 26 Mar 1942: | Discharged Royal Australian Air Force, Flying Officer, 400708, No. 7 Squadron (RAF), Date of death |

Help us honour Geoffrey Thomas Heard's service by contributing information, stories, and images so that they can be preserved for future generations.

Add my storyBiography contributed by Faithe Jones

Son of Walter Cory Bromell Heard and Ethel Lillian Heard, of Willaura, Victoria, Australia.

TO LIVE IN THE HEARTS OF THOSE YOU LOVE IS NOT TO DIE

FOR KING AND COUNTRY

FLYING OFFICER GEOFFREY

THOMAS HEARD

Flying Officer Geoffrey Thomas Heard, son of Mr and Mrs W. B. Heard, of "Carinya," Willaura, was reported missing, on 26th March, 1942, when the Stirling bomber of which he was captain failed to return from a operational flight. It has now been learned through the International Red Cross (says the Ararat "Advertiser") that he and his crew were all killed and are buried in the Catholic cemetery at Gendringer, in Holland. He had taken part in many raids on Brest, Essen, Emden, Hamburg, Kiel, the Renault works at Paris and on Duisberg, where the final raid took place.

Enlisting in the RAAF in April, 1940, the young airman left for Canada in February of the following year and three months later he was sent to England, where he was promoted to flying officer and attached to an RAF bombing squadron. It was a long way from his father's farm near Willaura to the airways over Germany and Northern France - to an airman's grave, in the age-old battle ground of Europe, and he has left a trail of cherished memories behind him. Geoffrey Heard had a natural zest for living, and will be remembered in his home town and district not only as a gallant airman, but as a genial associate, and friendly rival on cricket and football fields, and as a willing worker for the annual shows of the Willaura Agricultural Society. When war came he left these youthful sports and interests and went out to do battle for a cause he saw to be just and right, and by his death "he has helped to ennoble life for all mankind."

He was 26 years of age.

HEARD.— Previously reported missing believed killed in air operations over the Ruhr, now officially presumed to have lost his life on March 26, 1942, Flying-Officer Geoffrey Thomas Heard, R.A.A.F., dearly loved youngest son of Walter and Ethel Heard, of Carinya, Willaura, loved brother of Jack, Frank, Isabel, Shirley (W.A A A F.), and Joyce.

STORY OF A FLYING OFFICER

The Willaura bomber pilot, Flying Officer, Geoffrey Thomas Heard, whose death on active service whilst returning from a raid on Germany in the Stirling bomber of which he was pilot, is recorded in another column, is the subject of a short story written by one of his friends in the RAF. The story was written by a famous British writer now with the RAF, who has published a book of studies of RAF personalities and their flying adventures. In the story, "K for Kitty," which was published in the London "News Chronicle," the writer disguised Flying Officer Heard's identity under the pseudonym "Harrison." Flying Officer Heard was a son of Mr and Mrs W. B. Heard, of Willaura. We reprint the story as follows:

"K FOR KITTY."

Harrison was one of those lean, brown, old-eyed Australians who seem to accept England with a tolerance that Canadians never know. If there were things about England that needed changing or setting right Harrison rarely talked about them. If there were better pilots I rarely met them. Harrison was quiet, modest, friendly and as tough as hell. It was not Harrison, but someone else who first talked to me of the idea that planes and ships have the same delicate and temperamental ways. Just as you find no two ships alike so you find no two planes alike ; just as you find ships that are heavy, graceless, unalive, so you find planes that are dull and wooden in the air. In the same way that seamen come to know, trust and finally get fond of a ship, knowing that she is a living thing and will never fail them, so pilots come to know and trust and get fond of a plane, knowing she will get them home. In every squadron there is, I suppose, a plane that everybody hates. Then some day somebody quietly wraps it up in a distant corner of the drome and everybody is relieved and glad. But in every squadron there is a plane that everyone likes, that is something more than a pattern of steel and wood, and instruments and mechanism, that is a living, graceful, fortunate and ultimately triumphant thing, and this was the sort of plane that Harrison had. Harrison's plane was a big four engined Stirling called K for Kitty. The kite, like Harrison, was no stranger to the shaky do. On a trip to Brest the bomb doors froze up and would not release. This was bad enough. But the starboard outer also failed on the journey home ; so that Harrison was obliged to land on three engines, with a full bomb load, in darkness ; the sort of heroism for which, at the moment, we have struck no special gong. On other trips other things happened. Something happened to the flaps ; the under-carriage jammed ; the radio went u s - it does not matter. For the heroism of overcoming such minor misfortunes there are no gongs either. After such trips Harrison naturally trusted and grew fond of K. for Kitty. Not that I think he ever said so. He would call the kite a good kite, or perhaps, if he were a little happy, a wizard kite. These events in K for Kitty bore, after all, only a very slight relation to suicide. It was not until the big Brest trip that anything really serious happened to the plane. I am not sure if this raid, made on a clear blue winter afternoon, when the sunlight was light orange colored and the horizon peaceful with light haze, was the biggest ever made on Brest. But that night many bottles were opened and many songs sung, and I conclude from that, at least, that it was very big. And among the many planes that went, Harrison was in K for Kitty. Nor am I sure if they tried to blow Harrison to pieces before he bombed, or after. Possibly both. Finally a force of Messerschmitts attacked him, in a rapid succession of ten, and put out of action every turret he had. Tracers tore at all angles through tho nose and body of the plane. It shaved the skin off the knuckles of Harrison and his second dicky. It smashed the inter-com and mortally wounded the engineer. Blood flowed over the floor of the plane, mingling stickily with oil. It was hard to stand up, and the gunners could not fire, and there was no warning voice in the intercom. Many other things happened that Harrison did not then know about, but was to learn about later. He was glad enough to see Spitfires coming up as escort and the Messerschmitts diving home for tea. He was glad to be out of it and setting course for home again. He was quite glad that K for Kitty was his plane. At home, in the bright calm golden air of the late winter afternoon Harrison brought her down gently and beautifully, making a perfect landing. He even succeeded in holding for some distance to the runway. And then everything that had not already happened began to happen at once. It was as if the kite had flown home held together only by strips of sticky plaster and string ; as if she were a toy plane, put together by children that could not withstand the vibration of contact with the earth. She began to fall to pieces suddenly, terrifyingly, and almost systematically. The starboard outer airscrew fell off, and then the starboard under engine fell out completely. Then the complete starboard wing fell out, and then both the fallen wing and the fallen engine caught fire. Just before she came to rest the port wing was flung high into the air like the arm of someone drowning, and remained there high and stiff and awkward and dead.

I do not know how Harrison and the crew got out of the plane, slipping and sliding in the oily blood and lifting the wounded engineer, then skidding and falling down in the blood again, the plane burning all the time, the main door jammed and only the forward hatch available for lifting to safety the heavy wounded man. It seemed at any moment that the plane might blow up. But somehow Harrison and the crew and the wounded man got out and the plane did not blow up. She was still there, in that lop-sided high flung position, flat-tyred, partially burnt, when I went across the field the next morning. Harrison was there, too, looking at her. He was pacing up and down. The burnt, ash-colored wreckage of the plane lay scattered in an almost straight line, across the grass. Beyond the last grey scraps of wreckage the tyro marks of the plane made brown parallel lines in the muddy grass as far as the runway. Harrison then walked up the tracks made by the flattened tyres, stooped down to look at them and then walked back, stooping down again. Finally, he came back to the plane. We stood there for a long time together, looking at the plane. We picked up scraps of wreckage and dropped them again in the grass. We looked at the flattened tyres and the broken undercarriage and the splintered turret. We examined the neat ugly lines of tracer holes, neat and straight as the crochets of a rising scale punched everywhere across the flat face of the fuselage. We stood under the high, up-flung wing, smashed by flak, that looked more than ever like a stiff, dead arm. We looked at everything in amazement and unbelief and then looked again.

Long after I left, Harrison was still standing by the plane. And once, as I walked across the field, I turned and looked back. He was still standing there in the same attitude, looking at K for Kitty. I could not see his face, but it seemed as if he were looking at something rather distantly. It seemed even possible that he was looking at something he could not see. It was the attitude of a seaman who looks across empty water for the last time and sees his ship no longer there.