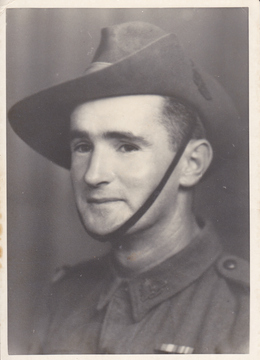

PORTER, Joseph Edwin Negus

| Service Numbers: | Q5637, QX13095 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | 20 March 1941 |

| Last Rank: | Private |

| Last Unit: | 2nd/26th Infantry Battalion |

| Born: | Maryborough, Queensland, Australia, 19 August 1918 |

| Home Town: | Not yet discovered |

| Schooling: | Not yet discovered |

| Occupation: | Hairdresser |

| Died: | Mackay, Queensland, Australia, 6 August 2007, aged 88 years, cause of death not yet discovered |

| Cemetery: | Not yet discovered |

| Memorials: | Ballarat Australian Ex-Prisoners of War Memorial |

World War 2 Service

| 20 Mar 1941: | Involvement Private, Q5637, also QX13095 | |

|---|---|---|

| 20 Mar 1941: | Enlisted | |

| 29 Apr 1941: | Involvement QX13095, also Q5637 | |

| 29 Apr 1941: | Enlisted Australian Military Forces (WW2) , Private, QX13095, 2nd/26th Infantry Battalion | |

| 28 Nov 1945: | Discharged Australian Military Forces (WW2) , Private, QX13095, 2nd/26th Infantry Battalion |

My Dad's Story in his own words

I, Joseph Edwin Porter (Ed) joined the A.I.F. on 29th April, 1941. Prior to joining the A.I.F. I was in camp with the 5th Lighthorse Regiment, which I had joined some months earlier.

After training camps I transferred to the 2/26th Battalion along with four of my mates and soon was on my way to Singapore.

Our camp in Singapore was situated outside the Changi village. After a number of weeks training in this camp, our coy, was shifted on to the bank of the Mirsing River, near the east coast of Malaya, where they thought the Japs were likely to make a landing. But they actually landed much farther north at Kotabaru where they were met by the British, Scottish and Indian forces and the first battle for the peninsula began. Our battalion was moved from our original position to an area surrounding a small township called Segament. Our first experience and knowledge of the action taking place further north was large numbers of wounded being evacuated by ambulance truck or any type of vehicle which could transport them back to the hospital. Some of the wounded were in a bad way, and weren’t exactly the sort of sight to urge the younger men on into battle. Our Battalion made first contact with the enemy at Gemas then had to leap frog the rest of the way down the peninsula as the Japs would avoid meeting us head on if possible, but by-pass us and get in behind to try and cut us off. This action continued until we crossed the causeway onto Singapore Island, where we were to make a stand but the Punjab Indian force on our left flank broke, and this let the Japs through. Our next and final stand was on the perimeter of the city itself, where we were dug in ready to fight to the last man, when the order was received to lay down our arms.

So began my experience as a Prisoner of War.

The group I was in finished up in the Selarang Barracks. I was appointed camp barber with very little experience, and precious little equipment to work with. However I managed to keep the men in fairly good trim generally. Then suddenly on or about the 10th May 1942, all men were assembled on the barrack square to be divided into special units and sent our different ways. I was with “A” Force, the first to leave the island for Merguri on the 15th May, 1942 in the “Celebes Maru”. We stopped enroute at Deli Sumatra, Victoria Point, the same night arriving at Mergui. Left on the 20th Aug and moved to Tavoy on Tatoo Maru, stayed the night at Ye, marched along the railway line to Lamanag and crossed the river to be loaded into salt trucks and were taken by train to Thambousayat, arriving at 6pm on the 8th Dec, 1942. We were taken by truck to the 26 Kilo camp, arriving 3 days later and started work on the Burma railway line the next day. I worked on various sections of the railway line until December 1943. Then we were on the move again working for a time working on the water front (being bombed on several occasions by our own bombers) among other jobs in Saigon, where the plan by the Japanese was to send us to Japan.

However it was not until the 6th of September, 1944 that we were loaded on the Rakuyo Maru, which was one of a convoy of twenty ships, which sailed from Singapore. On the 12th of September, I had just come up on deck from the hold, which resembled a sheep transport, having three decks built to enable us all to fit in. We could either lie down or sit up, as there was little room to do anything else. As I arrived on deck at 5.20am the first thing I heard was a huge explosion and a great red flash of light which happened to be the escort destroyer on our right flank which had been torpedoed, and sank almost immediately. Naturally there was a great hullabaloo from the guards, but they weren’t expecting what happened in the next few minutes. One torpedo struck the bow of our boat. The force of the explosion seemed to put about a foot of water on the deck almost immediately, then before we had time to think, another torpedo struck amidship and the engine stopped immediately, and the ship listed to the leeward side at about 35 degrees. By this time, the guards, both Japanese and Koreans with the help of our men started to release the lifeboats. As they reached the water, they were soon filled by the guards, and any of the men who were lucky enough to get aboard, only to be knocked back with a rifle butt or boot. There were heads bobbing about in the waters as far as the eye could see. My mate, Bluey (Arthur Watson Kay) and myself were the last two left aboard ship (excepting the only person who was killed by a safe squashing him to the deck – a guard). We had to cut the only remaining lifeboat free, because we couldn’t manage to get it down otherwise.

When it hit the water from such a height, it split enough to take in water. Nevertheless, by the time, Bluey and I climbed down the rope, there was scarcely enough room for us to get in but we managed somehow. We then made haste to get clear of the ship before she sank. We need not have hurried, as it was almost dark before she finally sank with a great “Banzi” going up from the Japanese, as they turned and sailed away in the night.

For the first night we tied three lifeboats together so as we wouldn’t drift away from one another during the night. This proved to be a failure as we didn’t seem to make any headway, so we decided to separate and go our individual ways hoping, as we thought, to meet again on the Chinese mainland which at that time we didn’t realize just how far away we were from land of any kind. During the night and again early the following morning we had heard machine gun fire and suspected that some of the other mates were being fired on and thought that we would see a patrol boat coming over the horizon at anytime, and receive the same treatment. But the firing stopped and we didn’t see anything of the other boats or men again. Brigadier Varley and his 2nd in command Lieutenant Smith were on board one of the other lifeboats.

The rest of the day and the next night were uneventful, except for the fact the some of the other fellows aboard were wanting to throw me overboard because I wasn’t in a fit state to pull an oar or help in any way, having malaria, beri beri and pellagra. This was the time when I found I had one true friend in Bluey. He defied anyone to lay a finger on me, or they would have him to deal with, so not a soul said another word.

We were able to stay afloat and survive on a couple of dog biscuits and a ration of water, equivalent to three eggcups full a day until 10am on the 14th September when we were “rescued” by a Japanese patrol boat. They placed us right up forward into the bow, underneath the muzzle of about a 6 inch gun. On several occasions, the Japs had alarm drill. I do not know whether the idea was to frighten us, but I feel sure had they needed to use that particular gun, we would have all been blown to pieces.

It took quite a few days for the Japs to get us to Japan due to the fact that they lost a convoy of ships that we were supposed to meet up with at one stage and again our transfer ship was also knocked out before we could meet it. We finally arrived in Kawashi, Yokahama on the 30th September, 1944, and I was in Camp 11D.

191 men including some Americans were in this camp and most of us were marched 2 & ½ miles each day to the Shibura Engineering works. The first snow fell on the 11th of November and we naturally felt it cold after coming from the steaming heat of the jungle. Our dress of hessian suit, cloth cap with our number on it, and whatever footwear we could find didn’t help us either. Wooden clogs were used in some cases, which were by no means warm.

On arrival in Japan I had lost the use of my legs, so each day I was put on a hand cart and two men were detailed to pull me to the factory, where I would have to shuffle around the best way I could with a witches broom and do any necessary sweeping that needed doing around the factory. Before I regained the use of my legs fully, I came down with pneumonia, and had to remain in the Shinagaua Hospital until the “Nips” decided it was time I was sent back to work. Fortunately during my spell in hospital I regained the use of my legs and was able to march along with the rest. Having been away for that time, I forgot to go on to the section parade which was immediately held before the main parade, and count taken before returning to Camp. When everybody was lined up, my number was called, and I had to step forward. Two guards came up one on either side and started slapping my face, first one and then the other. I would roll with the slap in order to make the blow softer, and also enable time to stay on my feet because I knew if they had knocked me down the boot would have gone in without any hesitation.

We had army guards over us as well as the Foo men as we called the civilian guards who were armed with sticks the size of broom handles. On one occasion one of the men had picked up a plate from the rubbish dump at the factory in order to have something to eat his meals at the camp. Sorry to say he never made it back to camp because he was unlucky enough to drop it during the march and was pounced on immediately by the Foo men and was beaten to death on the spot.

The first bombing took place on the 4th April, 1945 mostly incendiary bombs. We could see the fires from our camp. It wasn’t long before our turn came with the second bombing taking place on the 15th April with the entire camp burnt by a stick of bombs spread the full length. Fortunately everybody was evacuated without injury.

On the 7th May, I started work at the Foundry Shintetsuat, Ngata, a small town on the west coast. The camp was something of an international base where Australian, English, Dutch and Canadians were together. The war ended while I was in this camp on the 15th August, 1945, but I had one of the best birthday presents ever when I received the official news on my birthday. On that day an officer parachuted into the camp to inform us that we would be on our way home within a few days. Our own Officer took over on the 19th August, and we finally left camp at 2pm to board a train for Tokyo at 8pm on the 5th of September. On our arrival on the 6th, we had to strip and be fumigated etc. then we were issued with clean clothing, the first we had even seen since the day of our capitulation. To top it off we saw for the first time in four years a white woman, who was handing out cups of coffee and doughnuts.

We were sent to Manila for quarantine and saw our first motion picture, “The Passing Parade” starring Deanna Durbin. We also had a special visit to the camp by Gracie Fields.

I finally arrived back in Australia docking at Sydney on 20th November, 1945. After a train trip back to Queensland and the formalities and medical examination at Holland Park I was overjoyed at seeing my Mum and Dad waiting for me. They had made a special trip down to Brisbane to welcome me home.

Written by Joseph Edwin Porter (Ed)

Submitted 21 April 2025 by Debbie Brooker