TREMEARNE, Arthur John Newman

| Service Number: | Officer |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | Not yet discovered |

| Last Rank: | Major |

| Last Unit: | Unspecified British Units |

| Born: | Creswick, Victoria, Australia, 28 June 1877 |

| Home Town: | Not yet discovered |

| Schooling: | Creswick State School, Ballarat College, Geelong College, Victoria, Australia |

| Occupation: | Lawyer and soldier |

| Died: | Killed in Action, Loos, France, 25 September 1915, aged 38 years |

| Cemetery: |

Dud Corner Cemetery, Loos, France |

| Memorials: | Ballarat Australian Ex-Prisoners of War Memorial, Creswick Honor Roll |

Boer War Service

| 1 Oct 1899: | Involvement Lieutenant, 1st Victorian Mounted Rifles |

|---|

World War 1 Service

| 25 Sep 1915: | Involvement British Forces (All Conflicts), Major, Officer, Unspecified British Units, 1st/22nd Battalion London Regiment attached 8th Battalion Seaforth Highlanders |

|---|

Help us honour Arthur John Newman Tremearne's service by contributing information, stories, and images so that they can be preserved for future generations.

Add my storyBiography contributed by Faithe Jones

Lieutenant Newman Tremearae, wounded at Rensburg, comes from Creswick, where his father is a doctor, and who belongs to a very old Cornish family. Lieutenant Tremearne is barely out of his teens. His great-grandfather, when a captain in the Royal Navy, figured prominently in the American War of 1814. Having missed a commission in the Vic. Permanent Artillery the lieutenant went on with his medical studies, and had not completed his course when the war called him out. His mother is a daughter of the late F. N. Martin, of the Ballarat Star. Tremearne is a tall, spare-looking young fellow, with gentle, almost girlish, eyes, but just the man to do all that is asked of him, as he evidently has done.

Biography contributed by Evan Evans

From Ballarat & District in the Great War

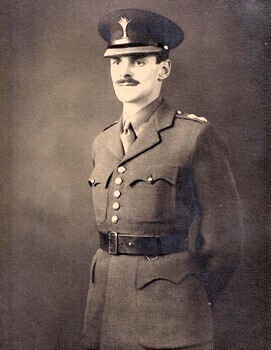

Major Arthur John Newman Tremearne

8th Battalion Seaforth Highlanders, (BA WWI)

1st Victorian Mounted Rifles (Boer War)

Imagine growing up hearing family stories of great daring-do, tales that dripped with history… From an ancestral grandfather lighting the beacon to warn of the presence of the Spanish Armada during the Golden Age of Elizabeth I, to a sea-captain taking on the might of a French Man o’ War to deliver His Majesty’s mail safely to New York - if this didn’t to inspire the ambitions of a child, nothing would. It appears that Newman Tremearne was determined follow in their footsteps and make his own mark.

So, strap yourselves in – this is one helluva ride!

Arthur John Newman Tremearne was a precociously bright child. He was born at Creswick on 28 June 1877. He was the first-born son of John Tremearne and Ada Jane Martin.

That he developed a keen intelligence was not at all surprising – his background was rich soil for the growth of enquiring minds…

The Tremearne family had a centuries-long connection to the Cornish seaside town of St Ives. Although named after the legendary missionary, St Ia, who was reputed to have floated from Ireland on a leaf, St Ives developed its reputation in more commercial ways. The local fishing fleet provided a thriving industry snaring the teeming schools of herring, pilchards and mackerel that filled the waters off the Cornish coast. St Ives was also a key port for the shipping of precious ore being mined around the area.

John Tremearne was born at St Ives in 1844. His father, John Newman Tremearne, was a local timber and general merchant, acting as an agent for Lloyd’s of London and the Vice-Consul for Portugal. The family was regarded St Ives gentry – when the Godrevy Lighthouse at St Ives was opened on 1 March 1859, the first name inscribed in the visitor’s book was that of John Newman Tremearne.

Although they were a prominent family, Tremearne was not a common surname. For those interested in naming origins , Tremearne comes from tre-warne, meaning dwelling by the alder tree.

After graduating with honours from the internationally renowned teaching hospital of St Bartholomew’s in London, John Tremearne (as a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons) was in charge of the Bath Hospital for a period of three years.

On his appointment as surgeon in charge of the Creswick Hospital in 1872, Tremearne made ready for his journey to Victoria. He reached Melbourne on 9 July 1872, having made the voyage onboard the sailing ship Norfolk.

At the time, Creswick was a thriving township, with a population close to 4,000 people. It appears that the new doctor made an immediate impact – he was charming (references were made to his ‘chivalrous personality’), honest (‘open-handed’), courteous and kind. His interest in mining speculation also saw him quickly amass a huge fortune through the Madame Berry group of mines at Creswick – he was described as a ‘plucky investor’ and ‘a fearless champion’ of the mining industry. In what most then revered as the truest indicator of character, Dr Tremearne was ‘a true type of the English gentleman.’

Few knew that John Tremearne was also a great contributor to local charities as he preferred to be anonymously altruistic in all his dealings.

It appears that this charming, erudite Cornishman was quickly taken with Creswick-born Ada Jane Martin. Ada was the daughter of Francis Nicholas Martin, then owner of the Creswick Advertiser.

Francis Martin was also a Cornishman. He was born at Gluvias in August 1827, but several attacks of rheumatic fever leading to chronic rheumatism resulted in him migrating to Australia prior to the goldrush. For many years he was employed as a resident master at the Melbourne Grammar School.

‘…When new reached the metropolis of some new rushes his caught the gold fever, relinquished his position as a teacher, and tried his luck with the pick and shovel. During those times lie “roughed it” with his comrades, and went through many of the ups and downs of a digger’s life. His experience, however, showed him that be was not robust enough for goldfields work…’

After journeying back to Cornwall to marry his fiancée, Grace Rowe (the ceremony taking place at Perranarworthal on 29 September 1853), Francis returned to Victoria to continue his teaching career. His final post was at the Creswick Wesleyan Day School. In 1864, he purchased the Creswick Advertiser and, in 1871, went into partnership with James H. Crabb and Edward Grose. With Grose, he then purchased the Ballarat Star in July 1884. His connections to journalism were to have an ongoing family influence.

When John Tremearne married Ada Martin on 27 September 1876, it was the closest to a society wedding that Creswick was likely to see.

‘…On Wednesday last the marriage of Dr Tremearne, resident surgeon at the Creswick Hospital, with Ada Jane, eldest daughter of Mr Martin, the editor of the Creswick Advertiser, was solemnised at St. John’s Church, Creswick, by the incumbent, the Rev. J. Glover, in the presence of a large gathering of friends and spectators. The wedding party arrived at the church punctually at 3 o’clock. As the bride, who was accompanied by her father, and followed by her bridesmaids, approached the altar the choir sang 'The voice that-breathed o’er Eden.' The service, which was choral, concluded with an address from the incumbent. The bride wore a white satin dress, veil of tulle; and wreath of orange blossom and lily of the valley. The bridesmaids’ dresses were of white, trimmed with blue. After the ceremony the ‘Wedding March’ was played as the bride and bridegroom and their friends left the church…’

The church was also the scene of the baptism of their first child. Baby Newman was baptised at St John’s on 7 November 1877.

The family home, “Pedn’ Olva”, adjacent to the Creswick Hospital, was built in 1881. By then John Tremearne had one of the most lucrative practices in the colony as the price tag of nearly £3000 clearly indicated. Although it would later be known simply as Tremearne House, the original name had a deeper meaning for John Tremearne, as Pedn’ Olva Point was once the site of a copper mine (of the same name) at St Ives.

Child mortality during Victorian times was unfortunately high. A lack of vaccines and antibiotics meant many common diseases could and did prove fatal. Even with a doctor in the house, the Tremearne children were not always safe. After Newman’s birth in 1877, the couple’s only daughter, Ada Avenel (known as Adèle) was born on 16 December 1878. Then came Francis Clement on 31 May 1880. But the little boy died on 15 February 1881.

Ada gave birth to three more sons – John Eliot (“Ruff”) on 23 November 1881, Frank Bazeley on 8 November 1883 and finally, Guy Howard (known as Rougo) on 29 June 1893. However, they were grief-stricken with the loss of their “darling Adèle” from pneumonia on 16 November 1890.

John Tremearne proved to be an outstanding physician. He performed quite radical surgeries for the period and used the newest and most advanced treatments for cancer. However, when his little boy Rougo contracted scarlet fever, there was little he could do and the child died on 5 June 1897.

Newman Tremearne grew up in this comfortable atmosphere. Surrounded by intelligent, inquiring minds, it was almost guaranteed that he would excel. He began his education at the Creswick State School, where his schoolmates included Lionel and Norman Lindsay.

When he was only 11 years of age, Newman became one of the original members of the Creswick Cadet Corps. It seems this lit a fuse in the boy that never dimmed.

In 1890, Newman was enrolled at Ballarat College, where he also joined the school cadets.

The death of his younger sister on 16 November that year, cut through the family in a most devastating fashion. So, in May 1891, Dr Tremearne took a leave of absence from his position at Creswick. The family spent six months abroad, mainly in England and Cornwall, where the children were introduced to the extended Tremearne and Newman families.

At the beginning of the new school year, Newman was enrolled at the Church of England Grammar School in Geelong. It became apparent that the young student was showing aptitude in multiple areas, leaving him with a plethora of choice when it came to possible career options.

Whilst at Geelong Grammar, Newman was once again an active member of the school cadets. But he was also developing a distinct musical talent and he held the position of bandmaster to the cadet corps. At the end of his first year, he was named as winner of the senior prize for music.

At the end of 1894, Newman sat the matriculation examinations held by the University of Melbourne. His passing result was announced on 4 January 1895.

Newman’s love of the military life saw him commissioned in the 3rd (Ballarat) Battalion in July 1895 – he finished top of the examinations for admission to the unit. However, he also continued his studies in music, sitting the junior theory examinations set by Trinity College, London, which he passed with honours. A presentation was held at the Ballarat City Hall on 19 November 1895.

In 1895, a musical group known as the “Nondescript Orchestra” began to attract attention around the district. Their conductor was none other than Newman Tremearne. They played in conjunction with the Thespian Club, with one performance held at the American Hotel in Creswick on 27 December. The following February, the orchestra performed a full concert programme at the Creswick Town Hall.

It seems that a career as a professional soldier held the greatest allure for the young man and, in 1896, he finished second in competitive examinations for a commission for the Victorian Permanent Artillery (forerunner of the Royal Australian Artillery). Although he had obtained more than the prescribed number of marks, Newman missed out on the appointment as there was just the one vacancy.

According to one source, he had ‘some idea of continuing his studies in this direction so as to make sure of the next vacancy, but abandoned it on being informed by a senior officer that if he joined the artillery, he would not be allowed to go to a war in the event of one breaking out.’ This caused Newman to rethink his career path, and he subsequently applied for and was accepted into the University of Melbourne to study medicine. He attended Ormond College, beginning on 1 March 1899 and immediately joined the University Training Corps for Officers.

By September 1899, it became clear that war in South Africa was inevitable. The following month Newman passed an examination as a captain of infantry. When the train carrying the local volunteers left the Ballarat Railway Station on 16 October, they were under the command of Newman Tremearne. Although he was just 22, and described as ‘a tall, spare-looking young fellow, with gentle, almost girlish, eyes,’ the authorities had good reason to believe he was ‘just the man to do all that is asked of him.’ It was an emotional moment, as thousands of people turned out to cheer the men off.

Newman was subsequently attached as a lieutenant to the 1st Victorian Mounted Rifles (VMR) at the Showgrounds Camp. Around this time, Ballarat’s William Thomas Brough (q.v.) was detailed as Newman’s orderly. The pair would share some remarkable experiences.

On 28 October, people packed along the streets of Melbourne “like herrings,” hoping to catch a glimpse of the troops as they paraded past. It was an imposing spectacle and ‘such a demonstration as never before has been witnessed in Australia.’

‘…The spectacle of 4000 soldiers on the march was well worth viewing, but the half-million of men, women, and children who thronged the city were intent only on one object—seeing perhaps the last of " our boys," and cheering them on their way with shouts of approval and expressions of good-will. Such enthusiastic cheering perhaps never before has echoed over Melbourne…’

Stirring music of a ‘patriotic strain’ played by the Artillery Band, would have thrilled the musician in Newman Tremearne.

The march covered four miles, before the men were conveyed to Port Melbourne pier, where the SS Medic was waiting to transport them to South Africa.

In a letter to his father, written on 6 January 1900, Newman wrote that the contingent was ‘under-officered,’ and due to Lieutenants Timothy McInerney and Henry Pendlebury being indisposed, he had taken temporary command of the Victorians.

‘…Colonel Rhodes, D.S.O. (brother of the Hon. Cecil) was in the same carriage. He is a weatherbeaten old man, and looks as if knew a thing or two. All the British officers with whom I had to do business were most obliging, and offered to do anything to help me. They are all very good, especially the seniors. A few of the newly joined ones try to put on a bit of 'side,' which, however, is as amusing as it is harmless.

Cape Town is full of soldiers, who are encamped all around. The Castle is used as head quarters for the various branches. Tommy looks lonely without the usual home accompaniments of nursegirl and baby, but the domestics are mostly coloured, which will, perhaps, explain it.

Volunteers are wanted, and can earn 5/ a day as infantry and 7/ a day as mounted men. Doctors and nurses, too, are especially needed.

The Canadians have drawn blood before us after all. We are nearer Modder River than they, and they were rather disgusted that we should be moved on ahead of them. I believe all the Australian and Canadian officers are to be offered commissions in the Imperial service without examination, if they want them…’

During fighting at Pink Hill (part of Hobkirk’s Farm near Colesburg) on 12 February 1900, where, ‘as an exhibition of resolute courage on the part of comparatively untrained troops,’ the Australians quickly won praise.

‘…On 12 February, the Boers attacked both British flanks. Situated on the extreme left, at Pink Hill, were 75 Victorians, 20 South Australians, 50 Inniskillings, and 50 Wiltshires. Major Eddy had assumed command of the post that morning from an Imperial Officer, who had moved off with the artillery to another position. The enemy attacked in considerable numbers just before noon, and for two hours Eddy's force defended grimly from among the rocks of Pink Hill. It soon became obvious that the position could not be held and the Wiltshire infantry were evacuated first, with the mounted men remaining to cover their retreat. Throughout the battle, Eddy had moved among his men, encouraging them and directing their fire, but no sooner had he given the order for the final retirement when he fell with a bullet through the head. The Australian casualties were severe: 6 killed and 23 wounded, of whom 10 were taken prisoner…’

(The Forgotten War – Australian Involvement in the South African Conflict 1899-1902 b12929955_Field_Laurence_Melville.pdf)

As stated, Major George Albert Eddy was killed during the fighting. Newman Tremearne suffered a severe wound near the ankle, leaving him incapacitated and at the mercy of his Boer captors. Although it would later be implied the they released Newman after discovering that he was a medical student, the real reason was probably more prosaic. The Boers fought a very mobile type of warfare and prisoners slowed them down. It was therefore a common practice to strip their captives of their uniforms, horses and weapons and leave them in the middle of nowhere.

According to Private Samuel W. Edwards, of Ararat,

‘…Lieut. Tremearne, who was in charge at Hopkirk's (sic) Farm, subsequently asked the boys if they blamed him for not surrendering, and their reply was characteristic. None blamed, but all said he had done his duty as a soldier, and Australians never surrendered…’

(Edwards suffered a severe chest wound in the battle. He would go on to fight with the AIF at Gallipoli and on the Western Front.)

Inexplicably, there appears to have considerable mismanagement of Newman’s wound. It was initially supposed that the bullet had struck him in the ankle and remained ‘buried’ in his foot. He spent several weeks being treated under this assumption, before ‘an almost healed wound’ was discovered near his heel. This marked the entrance wound and the ankle wound was where the bullet had passed through. It was then realised that his tibia had been fractured.

Due to the delays in reaching a correct diagnosis, Newman suffered for an unnecessarily extended period. However, he was young and ‘in the end his injuries were amenable to treatment.’

Early in his recovery, Newman decided to go riding for a little exercise. The surgeon overseeing his case believed it would do ‘no harm.’

‘…In a still weak condition, he mounted a pony which was guaranteed quiet, but proved to be frisky and hard-mouthed, and, without taking the precaution of having a curb adjusted to the bit, went for an afternoon ride. The pony shied at something, then bolted, and, to avoid being borne at full gallop through a crowded street Mr Tremearne threw himself off. He wonderfully escaped more serious hurt, but broke his injured leg at a point a few inches higher than the previous fracture…’

Newman was admitted to the Wynberg Hospital, where he was visited by war correspondent, Major William Thomas Reay, who was also an officer in the VMR. Reay was a 'chirpy, sparrow-like man' with a remarkably kind heart. It seems the pair shared a strong bond and Newman would often write long, chatty letters to the older officer.

Realising that his involvement in the conflict was at an end, Newman was given the option of being treated at the Military Hospital at Netley in England. He was accompanied by his orderly, William Brough.

He was amongst some 250 officers and men invalided to England onboard the steamship Ulstermore, leaving Cape Town on 1 June 1900. They reached the Royal Albert Docks just over three weeks later.

‘…The men were met with ambulances and other vehicles, and conveyed to the Herbert Hospital, some of the milder cases being sent to barracks on account of the great demand for accommodation at the hospitals. In passing through the streets the men were heartily cheered, and tobacco and cigarettes were given them…’

Towards the end of July, Newman wrote to Major Reay.

‘…The Thames was reached on the 21st June, and while going up the river we were saluted, by all the steamers, tugs, boats, etc., which passed. Two training ships were touching sights, the boys manning the yards, and the bands playing Home, Sweet Home. The Ulstermore, was docked too late to land that night, but all were disembarked early next morning.

I stayed at first at Blackheath, and was afterwards at the Hotel Cecil (Strand) for five weeks.

There is a great, number, of Australians in town, and some wrote and others called, with the result that I did not on the average have one meal a day at the hotel.

One notices in England the absence of noise of wheels in the streets, which is accounted for by the use of rubber tires. Could not someone subscribe for a few in Melbourne?

I went to Newmarket for a day’s racing with Mr W. T. Jones, and was made an hon. member. The Prince of Wales, the Jersey Lily, and her daughter, and other celebrities, were there, some good-looking, some not. The course cannot be compared with any of those at Melbourne, but might do very well for a back-block meeting. Ted Sloan won a couple of fine races.

Some Australians were at a garden party last Friday, given by Lora and Lady Brassey, at Normanhurst. A special train took ns to Battle—the nearest station—where we were met by bis Lordship. A storm had come on unexpectedly on our way down, and, as open drags were 'provided to drive to the house, we were very wet. The rain having stopped, we inspected the horses, Jersey cattle, and other animals of the estate.

We dined early, so as to catch a train back about 8, arriving in town at 10.30. All had a good outing, despite the fact that Lord and Lady Brassey were unlucky in their day as those before and after were fine.

I have been to very few concerts or theatres, but with those I have visited— including “ School for Scandal” (Haymarket), “ San Toy” (Dalv’s), and the Empire—l was very much disappointed.

I have heard Miss Lilian Devlin and Mr Percy Grainger, and both are, of course, very good. Madame Melba is as great a favourite as ever, and all praise Miss Ada Crossley. lam anxious to hear Miss Maggie Stirling, whom I have seen. She is getting on well.

People here are heartily sick of the Boer war, with its continual ambushes, etc., and the papers devote one column to the South African and four or five to the Chinese events. The latter is considered much more serious, though it does not affect us vitally, but European complications are feared.

The ClV’s [City of London Imperial Volunteers] have quite taken the place of the Colonials in the estimation of the public, and there is still a nasty taste in the mouth about, the volunteering of the N.S.W. Lancers. Why has this never been properly explained in the British newspapers? One would think the Agent-General would have had enough interest in his country to have done so. I am sure Sir Andrew Clarke would not have allowed such things to be said and written of Victorians as the representative of N.S.W. has seen fit to let pass undenied. An official account should certainly be sent, for the mistaken idea about those who returned reflects on all Australians.

I still have trouble with my foot, and am very lame. Another medical board sits on me next month, which will probably send me to Australia instead of South Africa. It would, I suppose, be useless going as I am at present, and as my place is filled up it does not matter…’

Although Newman only made passing reference to Blackheath in this letter, there was potentially greater significance that would later play out for him personally. Tudor House on Blackheath Park was the London home of his cousin, Shirley Newman Tremearne, who was the proprietor and editor of the Calcutta weekly newspaper, Capital. This was perhaps the first time that Newman was to meet Mollie Tremearne. Two years older than Newman, Mollie (whose proper name was Mary Louisa) had the added mysterious glamour of having been born in India – her birthplace was Serampore in West Bengal, known as the city of the major Hindu deity Rama. Her younger brother, Richard Hastings Tremearne, had served with a battery of the CIV in South Africa. He was commissioned as lieutenant with the 5th Warwickshire Regiment in November 1901, before returning to South Africa. He died from enteric fever in the Northern Cape Province town of Carnavon on 14 April 1902.

By the end of the year Newman had recovered from his injuries and he was ready to embark on his next adventure – special services officer with the Colonial Office to Ashanti. According to Sir Andrew Clarke, he had also been conferred with the honour of the freedom of the City of London.

This venture was referred to as the Ashanti Expedition in the newspapers, but it was more of a colonial policing operation designed to protect gains from the Ashanti War of 1900. Colonel Sir James Willcocks, who led the relief of Kumasi during that conflict, also headed up this delegation.

Extracts from a letter written to his parents from on board the SS Jebba, as it neared the West African coastal town of Axim on the 16 November 1900, made their way into Australian newspapers…

‘…We reach Axim tonight, Sekondi tomorrow, and the long looked for Cape Coast on Sunday. We remained a few hours at Sierra Leone, which is lovely and not at all like its reputation of “The white man’s grave.” Freetown, its capital, is prettily situated at the foot and on the sides of steep mountains and at the mouth of a river running seven knots an hour. There are three bays in the harbour – Pirate, English, and Kru Bays – in one of which was HMS Forte. The most conspicuous of the mountains are Sugar Loaf and Sierra Leone (2,500 feet). These rise gradually from the low hills covered with tropical forest growths at the sandy shore.

Freetown – known as the Liverpool of West Africa – possesses some stone buildings, the most notable being the English Church and the principal stores. The white barracks of the West India Regiment occupy the healthiest position, being on a low hill above the fever area. The streets are not paved, but are overgrown with grass, except in the centre where it is worn away, with the red soil showing.

The Mohammedans, Mandingoes and Foulahs wear long loose shirts with black mohair or silk gowns over them. The other natives are not so much dressed. The men have loin cloths or “utamas,” or perhaps a hat or coat from the cast-off wardrobe of some white man. The women (mammies) wear “utamas” and shoulder cloths and bustles; the baby is placed in the upper cloth and seated on the bustle. Young girls (secsters) wear “utamas” and beads around the neck, while the girl babies (tee-tees) have a string of beads only.

Very good leather work is turned out here in the shape of sheaths for swords and daggers, plaited hats and gui-gui bags (charms with a verse from the Koran written inside). Fruit and vegetables are fairly plentiful and of larger size than further down the coast. Cheap beads and rattles made of beans, are also sold, besides kola nuts, monkey skins, porcupine quills and snails, which are beaten up to make sauce.

The streets are full of goats and sheep and jack-crows, but these do not strike one so forcibly as the smell and noise. The natives yell – one cannot say talk – to one another and knock into each other with the greatest composure and satisfaction. Horses cannot live here.

A railway has recently been opened.

Sierra Leone looks best from the sea – when one is leaving, and though very interested, I was not at all sorry to go on further, and shall be happy when I land at the base of communications of the Ashanti Field Force. I hear the war is not nearly over, so I shall be in time for some fighting. We stayed at two ports on the Liberian coast and took Kru boys onboard. Liberia is a republic of free blacks, possessing a navy of two ships on which the lowest man is an admiral, and an army, where one begins with a captaincy. The capital is Monrovia.

More boys came on yesterday at Cape Palmas – a German settlement. We now have over 500 of all ages huddled together on the fo’castle and for’ard hatch, with no shelter but what they obtain from each other and from their scanty clothing. They are just like animals and sleep on top of one another, chattering incessantly when not asleep. There are no women amongst them, as these are hired by the Government on work of different kinds, mainly as carriers.

The costumes I have described before, but the “great swells” have wooden boxes, like those used for boots in Victoria, in which they keep carefully locked up their belongings – an extra “utama,” another cap perhaps, a spare bead or two and a______ string – worth altogether about 6d. These are rowed out from the shore in canoes called “dug-outs” made from single logs. These travel very quickly, are very light and require continual baling. The paddles are somewhat like flattened spears. We throw them sugar and bread to scramble for. They seem to enjoy the fun as much as we, pushing each other over and not caring what filth the tasty morsels fall into. Sixpence produces almost an uproar and when, yesterday, a lady threw a shilling, they scrambled for about 10 minutes and then commenced fighting in real earnest. As they only push or hit with the open hand, not much harm was done.

The niggers make a tremendous row yelling to one another. They are splendid workers, strong, faithful, honest (except when they’ve learned the value of things), but are frightful and cannot be trusted as allies or even as carriers at the Front, for they generally drop their loads and scatter if the sound of firing comes too near to be comfortable. They are all right though at the Base.

The Hausa and West Indians are just the reverse and are splendid fellows to fight. An officer at Sierra Leone told me that their only care is for their white officers. They risk their lives by showing themselves to draw the fire of the enemy, who usually waits for the white man…’

A second letter was written to his parents from a former slave fort on the Gold Coast of West Africa. [Note that gaps in the letter are due to illegible print].

‘…Acquah’s Hotel, Cape Coast Castle, November 20th – We arrived here on Saturday afternoon and came ashore on surf-boats costing us between 8s and 10s each. I put down my name at once at the Base head-quarters and next day saw the Commandant-Col Stuart. He reminds me of poor Col Umphelby, was very kind, and put me up to most of the tips.

I leave for the Front tomorrow. Do not yet know how far I am to go, but expect Kumasi, with the following personal retinue – eight men to carry the hammocks, four at a time, and ten as baggage carriers, the loads being of 50lbs. We take flannels, stores, as well as uniforms. I take one boy as cook, to whom I pay £2 a month, and a small one as servant, who is to get 10s a month. I think some non-coms are being sent with me, and as we shall very likely be in company with an engineering party we shall be an imposing force.

Amongst our baggage we have two “chop boxes” – all food here is called “chop”; in these boxes we put our cooking pots, milk, cocoa, tinned meat, etc. Rations are issued weekly at the different stations up the route. These are generally from 15 to 20 miles apart. My first stopping place is Dunquah – 25 miles off. I am staying at an hotel built by a native chief, ______. The building is of white-washed _____, situated right in the midst of natives, ____ as the men drink, play draughts and quarrel all night, the mammies sing to the ____, and the small boys and girls yell _____ over in the gutters, a quiet night is not easy to get. Concertinas, whistles, drums and fifes and a harmonium here and there never cease, but seem to have relays ____ players. I have scarcely stopped ____since I landed. The natives ____ everything as a joke and go off into ____ of laughter at everything one does. They are very happy, but extremely dirty _____ never wash. It is now 8.15. I have ____ to the Castle and head-quarters, get ____box and leave my heavy baggage at the Base office…’

In the same mail was a letter to Lieutenant-Colonel Reay.

‘…Since writing to you last I have travelled about a little. I was then in Edinburgh, and after leaving that city returned to London for a few days. On the 15th August Dr Masters (formerly of Melbourne University) and I went on the Continent. We first visited Paris by the Newhaven-Dieppe route (we had both been by the favourite Dover-Calais on previous trips), travelling about ten hours altogether. Of course, the Exhibition was the great attraction, and we saw it everyday. You must know by now what it is like, as so many visitors have described the great show, and so I shall only say that, as a whole, the Exhibition was magnificent, especially when viewed from a balloon or the Eiffel Tower, but hardly a side show was worth visiting.

The Court of Great Britain was the dirtiest in the Rue des Nations, and the British and colonial restaurant was the dearest and worst of the cafes. West Australia had a few logs of wood in a small house near the Transvaal Court (which was, of course, always full), but we didn't notice exhibits from the other Australian colonies.

After a week in Paris we went to Brussels, and there, amongst other places of interest, saw the house in the Rue de Cendres in which the Duchess of Richmond gave her famous ball the night before Waterloo. The building is now a convent, and has most of its windows bricked up.

We witnessed a reception of the Shah of Persia outside the Palais Royale. The soldiers were much in evidence, and their uniforms were very well, say, picturesque.

The Palais de Justice, the largest of its kind in the world, and the Cathedral are very fine buildings. We visited the field of Waterloo on top of a coach on a very wet day, and got some photographs. Some Americans in the party bought numerous buttons and badges picked up on the battlefield. Strange, that even after all these years, there is no dearth of buttons, perhaps they multiply in the ground.

From Belgium's capital we went to Holland, passing through Antwerp Museum and Cathedral, Dordrecht, Rotterdam, La Haye, and Amsterdam. Here we heard a ladies' orchestra and Sousa's (American) Band and saw a most beautiful and realistic reproduction of Spion Kop at the Waxworks. Three days sufficed here, and we returned to London via Flushing and Queenborough.

After a week in London I went to Cornwall, staying first at Lostwithiel and then at St. Ives. While here, I received a telegram from the Colonial Office saying that I had been selected for special service in Ashanti, and could sail on the following week. I returned at once to London, and after having invested in a new kit (my old one being in Capetown), was informed that the Victorian Government had objected to extending my services. I then volunteered to go without pay from Victoria, and started last Wednesday, resigning my commission (on the understanding that I am to be re-instated to my rank and seniority on my return) and giving up all claim for compensation.

The return of the CIV's [City of London Imperial Volunteers] was made the occasion of a tremendous display of enthusiasm and rowdyism, and numbers of absurd letters were written to the papers about their deeds of heroism. The Lord Mayor told them they had set a grand example to the colonies, which is not quite plain, considering we had all been in action before the C. I. V.'s were heard of. Some of us had a window in St. Paul's churchyard (at L1 1s per seat), and had a splendid view. I could have been an A.D.C. to Lord Belhaven if I had known in time, but was only told of it next day.

A cousin of mine returned with the H.A.C. Battery. He went out to South Africa in the same boat as I came to England in. I have now six cousins at the war altogether, one of whom has been killed and two wounded…’

When Newman arrived in Kumasi, he was caught up in a rapidly deteriorating situation. The native troops with the West African Regiment had not been paid for months, despite promises from the British Government. The unrest boiled over into mutiny on 18 March 1901, with the men firing on British troops. It took three weeks for order to be restored, and a subsequent trial saw 134 men imprisoned at Sierra Leone. Newman was promoted to the rank of captain and acted as adjutant to the West African Regiment whilst they were stationed at Sierra Leone following the mutiny.

On Saturday 21 September 1901, a representative gathering of Ballarat’s elite military officers – including William Bolton, John Sleep, Graham Coulter, Alex Greenfield and Alfred Willoughby Williams, along with Mayor J. J. Brokenshire and Archdeacon William Tucker, gathered at the Ballarat Railway Station to await the arrival of the Adelaide Express. Dr John Tremearne stood proudly waiting for his soldier son to alight from the train. William Brough was also present to greet his former officer. The men then gathered in the station’s luncheon room to take part in the usual speeches and toasts. There was a deal of pride in knowing that Newman had received his promotion whilst overseas on active duty – it was also noted that he had been appointed as an umpire in a recent Bisley rifle shooting match.

In response, Newman said that

‘…Although he was pleased to get home again he was prepared to volunteer for active service in the future should such opportunity arise. He was very glad to meet all his old friends again, and he could assure them that while away he had always thought of Ballarat and his friends…’

Newman and his father left by the 8 o’clock train for Creswick, where his mother and most of the town were waiting to welcome him home.

A banquet was held at the Creswick Town Hall on 28 September, where Newman was again feted with grand speeches and much applause. The ladies of the Creswick bowling and tennis clubs also entertained him to afternoon tea.

In response to Newman Tremearne’s rise in status, he was summarily elected to the Creswick Borough Council in 1901. However, when in September 1902, it was announced that John Tremearne had sold his Creswick practice and was leaving for Melbourne, Newman immediately resigned the position.

Now, if anyone thought that Newman’s romance with Africa or his thirst for adventure had abated they could not have been more wrong….

In 1903, Newman was chosen as on of the first batch of officers to form a police force in Northern Nigeria. He was the first to complete the detachment and was promoted to the post of staff officer. When the commissioner, Sir Frederick Lugard, went on leave, Newman was appointed to act for him and spent four months in command of over 1200 officers and men.

For the next three years, Newman lived amongst the native population of Nigeria, where he was employed as the District Superintendent (and adjutant) of Police, with over 4,000 men under his command. His fascination for the people, especially their customs and superstitions, was to become the central theme for the next stage of his life. Remarkably, he also found time to study French.

His work in Northern Nigeria chiefly consisted of travelling from one centre to another with the object of maintaining peace with the natives, who, it was said, ‘are very warlike and continually mutiny against English government.’

Photographs sent to his father were published in the Melbourne Leader. The grainy images include shots of Newman with his attendant and another of the crossing near Bramaquatah, between Lafarge and Ilorin.

In early 1906, Newman left for England to take up a scholarship at Cambridge University to study Arabic and the Hausa language. The scholarship was open to all of West Africa, carried a prize of £80 and three terms at the university. He was also named a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society of Australasia. It was proposed that he would return to Nigeria in June that year.

This was also a more personally significant time…

‘…St. James's Church, Kidbrooke, Blackheath, was on 23rd April the scene of the wedding of Captain A. J. Newman Tremearne, F.R.G.S.A., of North Nigeria, son of Mr. and Mrs. John Tremearne, of Melbourne, and Miss Mary Tremearne, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Shirley Tremearne, of Calcutta, and of Tudor House, Blackheath Park, London.

The service was fully choral, and the church beautifully decorated, the ceremony being performed by the Rev. J. W. Morris, assisted by the Rev. H. W. Snell. The bride was given away (in the absence of her father in India) by Dr. Thursfield, and she wore a gown of white satin, draped with old Duchesse lace, made with a long court train. Her lace veil covered a tiara of real orange flowers, and she carried a bouquet of white roses and lilies of the valley.

There were three bridesmaids gowned in pale blue chiffon-taffetas, with large white crinoline hats, white feathers and a single crimson rose, and they carried bouquets of crimson roses. Mr. C. Morley, W.A.F.F., was best man.

The numerous guests, including friends from Australia, India and Africa, were afterwards welcomed at Tudor House by Mrs. Tremearne, and the bride and bridegroom. Captain and Mrs. Tremearne, departed for their honeymoon amidst showers of primroses, the bride wearing a white cloth coat and skirt, white hat wreathed with pink roses. Numerous handsome presents were received…’

Whilst Mollie remained in England, Newman returned once again to Nigeria. This meant he was not present when their baby daughter, Elizabeth Joan Newman, was born prematurely in December 1906; sadly, the baby lived just a short time. She was buried at the Charlton Cemetery in Greenwich on 6 December.

There were no further children.

Meanwhile, Newman was continuing to advance his career in Nigeria. At his own request, he was transferred to the political department and was sent into remote areas to govern pagan tribes in the protectorate. The greatest opposition came in the Bautchi Highlands, where the ‘unfriendly and shy’ people used the rugged land to their advantage. The administration adopted a policy of ‘peaceful penetration,’ hoping to minimise unnecessary unrest. For those men pushing into these remote regions, the discovery of an enormous population was entirely unsuspected. They were ‘naked and addicted to cannibal practices,’ which appears to have been equally shocking.

That Newman’s work was dangerous was an understatement – he was wounded twice during this period (1908-09), once having his face grazed by a poisoned arrow. But it was the prevalence of disease that was more dangerous than the natives and eventually led to the end of his African career.

In 1910, after seven years in Nigeria, Newman was forced to retire from his position in Nigeria due to ill-health. He was ordered not to return to Africa for at least three years following a severe attack of blackwater fever and repeated bouts of malaria.

Ultimately, this enforced retirement led to the most productive stage of his life.

For the next few years, Newman concentrated on his studies at Christ’s College, Cambridge. On 24 May 1910, he received the Diploma in Anthropology – the first time that a diploma had been awarded in the subject. The work submitted to the Board of Anthropological Studies comprised two papers: Notes on some Nigerian Head-hunters; and the Origin, Language, Folklore, and Physical Development of the Hausas.

Newman also maintained his military life – on 25 December 1909 he was gazetted to the rank of major; then, on 18 March 1911, it was announced that he had joined the 22nd (County of London) London Regiment, known as The Queen’s Regiment, where he was appointed second in command.

He later passed his examinations for lieutenant-colonel.

Proving a true polymath, Newman submitted an original version of Australia, an Empire hymn, , which was accepted by King George V in 1911, and was published by The British Australasian as 'A Coronation Hymn.’

Australia! Australia!

Of Southern Seas the Queen,

In Nature's rich regalia

None fairer can be seen.

The Cross's silver tracing

Gleams o'er thy golden land,

And three seas thee embracing,

Softly kiss thine opal strand.

Ye Nations! Do not wonder

If Austral's Sons are true:

Where England's guns may thunder

There ours shall thunder too.

We share her grand old story,

The cost we've helped to bear

Our duties are our glory

So Australia will be there.

Old England and her Daughters

A might Empire form,

Close knit by wars and slaughters,

Made strong by stress and storm.

O God! Help thou our legions,

As roads to fame they hew,

To hold these world-wide regions

Which e'en Caesars never knew.

One God, One Hope, One Nation,

One Flag, One Emp'ror King!

Let all, what'er their station,

Their Country honour bring.

The Mother-Isle is plighted

To Children great and free;

Close are the lands united

God has girdled with the sea.

On 26 April 1911 the results of the Easter Examinations were announced with Newman passing the Council of Legal Education – Hindu and Mahomedan Law Class III.

His knowledge on West Africa allowed him to speak confidently on a number of subjects. In a letter to the editor of the London Times on 14 July 1911 regarding liquor in Nigeria, Newman wrote,

‘…Sir, I have read your Special Correspondent’s article in today’s issue with great interest. I gather from it (though, I admit, with some surprise) that there is no illicit distilling in Southern Nigeria on account of the abundance of imported liquor. In the sister Protectorate to the north, where the importation is prohibited, distilling is carried on even in many Mohomedan districts, and the Government recognizes it by the grant of special permits – costing 3s 6d per month, if I remember rightly. In the pagan districts to the north-east of the Nassarawa Province the natives make most of their millet into beer (or akann, as they call it), so that from about June to October in each year they are in a state of semi-starvation. Every one, therefore, robs his neighbour of is possessions in order to buy food, and these acts naturally cause fights, and perhaps even loss of life. No doubt hunger was one of the principal causes of slave-dealing in these parts. It is a pity – so far as these particular people are concerned – that the importation of our liquor is prohibited, especially if the Committee of Inquiry be right in saying that gin is less injurious than pito, for the natives will drink, whatever we do, and if able to obtain our spirits they would probably keep their grain for food, and so live a more contented and peaceful life. I do not mean to imply that it is better for a native to drink than not to drink. I only say that he will drink, and that, if he is brought to a state of starvation thereby, there will be trouble…’

He followed with a second letter on 22 July,

‘…Sir, In reply to Mr Earle’s letter in your issue of the 19th, I beg to point out that I did not state that the Government recognizes the practice of distilling spirits, for the word “spirits” was not used. However, lest there should be any misapprehension, I admit that “manufacture” (the word used in the proclamation I referred to – the Native Liquor Proclamation) would have been better than “distilling.” I was thinking of the result, not of the name, and the change of the latter does not affect my argument in the slightest degree. Perhaps I should have mentioned – though it did not occur to me as being necessary at the time – that the Government does not encourage the manufacture of liquor in any way, and the distillation of spirits is prohibited, as Mr Earle states. The fee is imposed, not so much as a means of obtaining revenue, as a check on the too abundant sale of the liquor. Still, the fact that there is such a fee implies that the manufacture is recognized as a necessary evil – ie, that the natives will drink whatever we do; and that is the whole of my argument…’

Newman successfully built a career as a lecturer in the Hausa language at Cambridge University. As a public speaker, he was often in demand. His subject matter was fascinating to his audience – many of whom had never travelled further than the end of their own town or village.

In many respects, Newman’s views and ways of expressing himself, may appear almost offensive one hundred years later. But one cannot fault his quest for knowledge and understanding. In presenting a paper to the British Association in October 1911, Newman put forward that in dealing with the natives you must ‘have a sense of humour.’

‘…The Hausas' evil spirit is Dodo. One story,' said Major Tremearne, 'relates how he was killed by a small boy in much the same fashion as our legend of Jack the Giant-killer. The hero usually cuts off the head or tail of the slaughtered enemy as evidence, but in one story he also leaves his boots behind, and there is a competition to fit them on among the warriors who pretend that they have done the deed, like that among the sisters of 'Cinderella.'

In 1906 my native police sergeant one day brought three constables before me, who accused their wives of being witches. The sergeant reported that the men were preparing to desert. I therefore summoned the women, and asked them if the charge were correct, and on being informed that it was, I placed them under a guard, not knowing quite what to do with them. Next day I put a galvanic battery on each in turn telling them that. They would feel the evil influence, pass right out of them, and, us they thought they did so, the matter ended happily. A simple trick may be much more successful than the most learned judgment sometimes…’

During the same talk, Newman told of an extraordinary dance called the bori – translated as a delirious person.

‘…The dancers appeared to be under actual hallucinations that they are certain characters. Initiation into the degree of bori dancer is a curious rite. The candidate has to eat porridge off the floor without using her hands; a black goat is killed, and there are mystic ceremonies... 'Then the bori starts to the tune of the fiddle, played by the margoge ('the doer of rubbing'). Some of the dancers go round and round in a circle until they have worked themselves into a fit of hypnotic-like unconsciousness, with eyes fixed and staring. Others accomplish the same desirable feat sitting down. Suddenly one of them will begin squealing or roaring, and after a little will jump up in the air and come down flat…’

He concluded with another piece of folklore:— ‘The donkey was once a denizen of the forest, but he quarrelled with the hyaena, who had respected him previously in the belief that his long ears were powerful horns. That is why the donkey finds it safer to live in town.’

Remarkably, Newman also completed his Bachelor of Laws at Cambridge. He was called to the Bar in January 1912 under the professional association for barristers and judges, Gray’s Inn – one of the four British Inns of Court. The listing referred to him as, A. J. N. Tremearne, BA, scholar and prizeman, Christ’s College, Cambridge, Hausa Lecturer, Cambridge University. He completed his academic career gaining a Bachelor of Science.

At St James’ Palace, on 11 March 1912, Newman was one of a large attendance of officers who took part in the King’s Levée. He was presented to King George V by Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Joseph Previté. His Majesty, attended by his Gentlemen in Waiting and escorted by a detachment of the 1st Life Guards, arrived at the Garden Entrance from Buckingham Palace, and was received by the Great Officers of State and His Majesty’s Household.

Mollie Tremearne (referred to as Newman’s ‘clever wife’) had been presented at Court the previous year by the Lady Henry Cavendish Bentinck.

On 14 November 1912, Dr John Tremearne died from heart failure, bringing a remarkable life to a close. After leaving Creswick, he had set up practice in Collins Street, where he became a specialist in hydatid disease, with patients coming from all over Australia and New Zealand to be under his care. In 1907, he had purchased Mandeville Hall in Toorak. His sister-in-law, Ella Row “Marty” Martin, ran an exclusive guesthouse from a wing of the home. (This business proved very profitable, and after her husband’s death, Ada joined her sister in its running). Numerous tributes made reference to his Cornish origins and fine character, whilst also highlighting the achievements of his son.

‘…He is an Australian who reflects credit on his country, and the hope has been generally expressed that his services will be availed of by the military authorities in this Commonwealth. He is a worthy son of an honoured English gentleman, for the name of Tremearne needs little recommendation, as the memory of his illustrious father lives deep in the hearts of countless residents in Victoria, where his integrity, ability, and striking personality endeared him to all who had the honour of his friendship…’

In 1912, Newman had received a grant from the British Association for the Advancement of Science; then, in 1913, he was the recipient of a Worts grant from the Cambridge University that enabled him to travel to North Africa to study the “demon cult,” which would become the focus for one of his many books.

Newman continued his prodigious output. In three years he published several books on his favourite subject. In 1912, he produced The Tailed Head-hunters of Nigeria: an account of an official's seven years experiences in the Northern Nigerian Pagan Belt; and A Description of the Manners, Habits, and Customs of the Native Tribes. The following year saw the publication of Hausa superstitions and customs: an introduction to the Folk-Lore and the Folk and Some Austral-African Notes and Anecdotes. His final work, The Ban of the Bori. Demons and Demon-dancing in West and North-Africa, was released in 1914. Mollie assisted him with work and collaborated with him on the writing of Fables and Fairy Tales for Little Folks, or Uncle Remus in Hausaland (1910). His work remains in print to this day.

The following review of The Tailed Head-hunters of Nigeria appeared in The Argus (Melbourne) on 22 March 1912.

‘…West Africa seems to have had an irresistible attraction for the author from his early boyhood; at the age of eight, he tells us, he marked the routes to Kumasi and Segu on a map; and when in 1900 he was offered the opportunity of joining the Ashanti expedition as a special service officer, instead of returning home with the Australian regiment, he seized the chance with avidity.

He finds himself unable to escape from the spell of the country; though he left it some years ago, he his life studying West African native anthropology ever since, so that in spirit he has still lived in that fascinating region. "If you've 'eard the East a-callin'," Mr Kipling's soldier tells us, "you won't never 'eed naught else." So it is apparently with the Gold Coast and the country that lies behind it; "the victim, once fallen, must obey," says Major Tremearne, "though it be against his better understanding. . . . and, whatever kind of wreck the coast has made of his body, I doubt if his mind ever frees itself of the charm of the old associations.

It is a high commendation of the book to say that the author somehow manages to get something of that strange inexplicable fascination into his pages; if he does not succeed in making us wish to visit the country he at least helps us to understand the charm it exercises on spirits more adventurous than our own.

The narrative part of the volume is generally interesting, and sometimes exciting; for life among the head-hunters is not devoid of incident, and the author has been through many tight places. "I suppose West Africa will some day be as safe as Ireland," he remarks; but he is plainly very glad that that day is not yet…’

At the time, not all reviewers were impressed with Newman’s writing. An un-named journalist for the Adelaide Register in November 1913, was quite dismissive. In reviewing Some Austral-African Notes, it was questioned why the book was prefaced (‘with no apparent purpose’) by three chapters on the Boer War ‘Interesting in themselves— and indeed, they contain the better writing— they are quite distinct from the bulk of the volume, and it is difficult to understand why they should have been inserted— unless for purposes of advertisement…’ The writer did seem interested in Newman’s insight into political motivation towards the military.

‘…He speaks of the shock to the Victorian men on finding that the wonderful new rifle with which they had been carefully entrusted a month before was already obsolete. The antiquated Martini-Henry, in general use in that State, had been replaced by the Martini-Enfield on the departure for Africa. Immediately on arrival in Capetown, they had to be exchanged for Lee Enfield. The same old story. "If the public is to pay taxes, it wants to see something for them in the way of reviews and glitter. . . .The Government (which, after all, is compelled to do as the voters wish) therefore starves the fighting forces, so as to have money to waste on education, in teaching the lower classes (the most powerful at the polls in a democratic country) to be dissatisfied with what they are, and to plot to push themselves into positions for which neither their brains nor their breeding fits them."…’

It was concluded that ‘the remainder of his book contains a multitude of words out of proportion to the information conveyed. There are interesting chapters on African warfare and fights with invisible cannibals, but the style of the narrative is so wandering and so diffuse that quotation is difficult…’ and that ‘there is interesting and novel material in this book, but much of the matter has been treated before, and treated more capably.’ In attempting to find some merit in the publication, it was noted that ‘the work is profusely and finely illustrated with photographs…’

Despite this negative assessment, Newman’s work was generally well received and was seen as a valuable contribution to the study of anthropology.

During 1913, Newman toyed with inventing a head-measuring device. It was modified after suggestions were made by eugenicist, Karl Pearson. Concerningly, Pearson was a proponent of social Darwinism and his views are now seen as scientific racism.

In July 1914, Newman, who had been working in Algiers, left for London to join up with other members of the British Association for the Advancement of Science who were to attend a congress in Australia. They travelled onboard the new liner, SS Euripides. Newman was the only casualty of the voyage – he slipped on the deck playing tennis and injured his foot.

The Euripides reached Melbourne on 10 August – just days after Britain had declared war against Germany.

As an Australian on the world stage, Newman was quickly sought for his opinion on the situation and the interview appeared in multiple newspapers.

‘…Foreigners for several years have held the opinion that war between Great Britain and Germany was inevitable, and the only people that were blind to the fact were the English themselves. Only last March I travelled with a French battalion of tirailleurs, consisting of native Algerian troops, from Morocco to Tunis, and I was told by the officers that they considered war between Germany and France inevitable. Since they regarded Britain as being bound to their country they were very uneasy at our apparent belief in Germany's peaceful protestations.

In Tripoli I found that the Italian officers held a similar opinion. They regarded with great amusement Lord Haldane's mission to Berlin. There is no doubt of Italy's friendship and admiration for England, in spite of the London Press campaign against her in her war with Turkey.

While in the city of Tripoli - where I was inquiring into the demon-dancing of the Hausas - Gen Garioni, the Governor, not only personally entertained me, but also detailed a major on the staff to motor me round the battlefields in the vicinity…’

Newman immediately made preparations for he and Mollie to return to England, where he intended to join Kitchener’s Army. Sadly, the injury to his foot precluded him from accompanying the group on their visit to the School of Forestry at Creswick, now housed in his childhood home.

On 18 August, Newman and Mollie boarded the Demosthenes for the dangerous voyage back to England.

After rejoining his battalion in London, Newman was ready for deployment on the Western Front. He was posted to D Company of the 1/22nd Battalion.

Before going to France, Newman wrote to his mother,

‘…The long waited orders have come at last and the camp has sprung into life again. This war will not be over just yet, and we hope to have a good hand in making history. There is no use in disguising the fact that war, especially this war, is a dangerous game, but counting by countries I ought to be safe, for I was shot in South Africa, and had my leg broken. In Ashanti nothing happened. In Nigeria I was hit by a poisoned arrow, and had my knee poisoned at another time in that country. This war should show no result therefore. Mollie will be sending you a copy of Lord Kitchener’s message to the troops…’

They landed at Le Havre on 11 May 1915. The 1/22nd Battalion was attached to the 8th Battalion Seaforth Highlanders.

For Newman Tremearne, trench warfare was vastly different to his previous experience. The 1/22nd went into action during the Battle of Festubert on 15 May.

The battalion subsequently moved to Souchez near Vimy Ridge, where the remained for the next few months.

Writing to his mother on 27 July, Newman said, ‘…It is difficult to see how it is all going to end. Even if Germany can detach an army from the Russian frontier I don’t think they could possibly get through our lines, and I doubt if they will try again. On the other hand, can we? There seems to be two alternative solutions – One, that one side or the other (we, I believe) will bring out some new terrific explosive which will blast away everything before it, the other that the financial conditions will determine the conflict, and in that event Germany is certain to lose. That would be a most unsatisfactory solution, however, and would be no guarantee for future peace. We must get to Berlin for the sake of our future generations.

The knowledge of the German cruelties sends one mad to be at them. Few British prisoners are left alive for the Germans want to exterminate us. We, on the other hand, do not hate the beasts sufficiently even yet…’

Then from “Somewhere in France” he wrote on the 8 August – ‘…In dry weather the trenches are not unpleasant when things are quiet; but one must soon become pale and flabby owing to the want of sun, air and exercise. Miners ought to be in their element, but there are no such things as 8 hour shifts. A shell burst this afternoon where I am generally standing. I being somewhat taller than most, was sniped three times the other day and later on a shell landed there during my absence.

The real nuisance is the sniping, and the Germans are very clever at it. There is not the slightest doubt that they get men through – or come up through France behind our lines, for shots come from unexpected directions. With our accustomed foolishness we suspect nobody – and suffer. Spies and snipers hide in old mine shafts, deserted attics, ruined churches, etc, and with say a month’s supply of food and 1000 rounds of ammunition can make things fairly unpleasant; carrier pigeons bring the necessary means of communication.

One cannot help admiring these fellows for their pluck, and it is useless and idiotic to think the Germans are not as proud as ever of their country and Kaiser. When plenty can be obtained for this dangerous work, we imagine that the Huns are tired of Bill II, because we are. It is a very great mistake. As the prosecution against the ‘Times’ failed, I suppose that one is safe in saying that in France I saw no idle young men, only the boys and dotards are left in the villages. It makes one blush for shame to think of “London as usual;” full of slackers, many of them parading with a badge or in imitation uniform, pretending that they are doing something.

The cursed thing about our system is that when the war is over the men who have stuck to their jobs will have saved money and have husbanded their health, while many of those who return from the front will be broken in purse and constitution. The voluntary system is a shameful farce, for by it the worse the loafer the bigger the bribe to get him. It is said to be an absolute fact that however much a man has been opposed to compulsion, directly he has been in the trenches he wants to get his old fellow workers out here. He has no longer any doubts about what real liberty and duty are.

I get only four hours sleep a day here now; however, I can very soon become used to that. I did not have very much more when studying my hardest at Cambridge and the Bar simultaneously. We have to sleep in our clothes, of course, and one is sometimes covered in mud for days. The work is interesting and there is always a great deal to be done and every man can feel that he has done something…’

In a later letter home to his mother, Newman gave a glowing description of his battalion, a large proportion of which he said was made up of “University men.” ‘They only want a chance and I am sure they would make history.’

Although most Australians would have been following the daily newspaper reports of action on the Western Front, few would realise that some of their own countrymen were involved. At Loos on 25 September 1915, the British launched a major plan designed to take the battle to the Germans. It involved the most violent preliminary bombardment of the war to date and was characterised by a large-scale commitment of infantry and extensive use of gas. Although some gains were made, strategic failures led to the inevitably high casualty count.

At the end of the first day of fighting, one of the finest of Australia’s sons was dead. Newman Tremearne had been killed in action. No detailed reports were ever made available.

To compound the situation for Mollie Tremearne, who was confined to bed through illness, her brother, Crew, who was serving alongside Newman, was listed as missing in action. It would be confirmed later that he had also been killed during the fateful charge at Hill 70, on 25 September.

On Sunday 10 October 1915, the people of Creswick and district gathered at St John’s Church for an in memoriam service to remember the lives of two local men who had fallen in battle – Private William Arden Egerton “Tom” Arnold (q.v.), son of the former vicar, who died at Gallipoli on 17 September and Major Newman Tremearne.

The congregation included Mayor John Jebb, councillors and officers of the borough, representatives of the military forces, and residents from all parts of the district, who attended to pay a tribute of respect to the memory of Major Tremearne. Ada Tremearne, with her sister, Marty, Newman’s brothers, Ruff and Frank Tremearne and Miss Emily Aspinall (an old friend of the family), all came from Melbourne to attend the service. The vicar, Rev James Rowland Hill, conducted the service.

Premier of Victoria, Sir Alexander Peacock, of Creswick, was called on to speak of two soldiers. Of course, Peacock had enjoyed a long association with the Tremearne family.

‘…He believed in the communion of saints, and as we come, as the relatives of Major Tremearne come together to St John’s, we feel that we are associated in spirit with the departed loved ones. The late Major Tremearne had lived 38 years, and what a lot he had packed into that life. He remembered stealing into that church to see the marriage of Dr and Mrs Tremearne. We knew the Major’s bright and cheery nature, and his father was proud of him, and he asked that in their prayers they would think of his (the late Major’s) sick wife. She was lying on a bed of sickness when her husband went out to fight; she had lost her husband, one brother was missing, and she had lost another [Lieutenant Richard Hastings “Dick” Temearne who died of enteric in South Africa]. Our sacrifices were infinitesimal compared with those of the mothers and wives. He was not there on his own accord, but at the request of the vicar and church people, who desired him to speak on the life and deeds of Major Tremearne and it was but little sacrifice on his time to do so…’

All present were aware of the remarkable achievements and experiences Newman Tremearne had crammed into his 38 years. Peacock continued, saying

‘…We sometimes see in the cemetery a broken column as a monument over some grave in which lies the body of one who, in our opinion, had died before his time. But here was no untimely end, no death demanding a broken column. His career may have been short in years, but it was long in years. He had told them in the Town Hall of Gladstone’s grandson, who said it was not the length of life one lives, but the manner in which that life was spent that counts. As one of the poet’s wrote –

We live in deeds, not years,

In thoughts, not breaths;

We should count time by heart-throbs.

He most lives

Who thinks most, feels the noblest,

Acts the best…’

On 4 August 1918, the community gathered once again at St John’s Church for the dedication of a new bell and two marble tablets, both presented by Ada Tremearne and her sons in memory of Dr John Tremearne and his son, Newman. Sir Alexander Peacock performed the unveiling.

‘…To the Glory of God and in remembrance of John Tremearne, MRCS, Eng, died at Melbourne, 14th November 1912. “A good life hath but a few days, but a good name endureth for ever.” Also of Arthur John Newman Tremearne, MA, LLM, MSc, Dip Anth, Cantab; Barrister at Law, Gray’s Inn; Lieut 1st Australian Contingent, Boer War, Capt Northern Nigerian Field Forces, Major 8th Seaforth Highlanders, killed in action at Loos, September 25th, 1915. “Faithful unto death.” This Tablet is placed as a memorial to her beloved husband and son by Ada Tremearne, and her sons, August 4th 1918…’

Ada Tremearne maintained an active and productive social life. She continued to live at Mandeville Hall until her death on 1 April 1942.

Mollie Tremearne did not remarry. She had learned to live through Newman’s long absences in Nigeria – it was estimated that they had only spent three years of their nine-year marriage together. But it seems to have worked for them. When Newman was studying, Mollie studied alongside him; they had made a good team.

For 24-years after the deaths of Newman and Crew Tremearne, In Memoriam notices appeared regularly in The Times. Each entry was worded exactly the same and always concluded ‘Till death us join.’

She died the Tynemouth Infirmary in North Shields on 28 August 1962.

In remembering Newman Tremearne nearly 109 years after his death, the words published in the magazine of Christ’s College, Cambridge, ‘Tremearne’s career is a wonderful example of inspiring energy, combined with those manly qualities which make the ideal soldier and administrator. He had studied in three Universities – Melbourne, Cambridge, and London – and had received the degrees of MA, LLM, and MSc, and the Cambridge Diploma and in anthropology, as well as being a barrister of Gray’s Inn. The publication, ‘Man,’ the record of anthropological science, pays a tribute to his studies of ethnology, and deplores his death.”…’

His was a truly wonderful life.