BLACKMAN, Thomas Francis

| Service Number: | R58123 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | Not yet discovered |

| Last Rank: | Leading Seaman |

| Last Unit: | Not yet discovered |

| Born: | Hendon, London, England, 23 April 1943 |

| Home Town: | Not yet discovered |

| Schooling: | Not yet discovered |

| Occupation: | Not yet discovered |

| Memorials: |

Vietnam War Service

| 15 Oct 1967: | Involvement Royal Australian Navy, Leading Seaman, R58123 |

|---|

MY VIETNAM STORY

Mahendra Blackman

Upper Duroby, NSW

Some accounts of incidents in Vietnam, including mine, are so raw they should come with a warning, an R-Rating perhaps.

Just after I was engaged to be married I was transferred to the now notorious Manus Island north of New Guinea, where I was in charge of the operating theatre and Malaria control. I also became a swimming instructor for the locals and the Depot Barber.

After returning to Sydney a year later I was crash-drafted to H.M.A.S Albatross, south of Sydney. I thought the feller was joking, but later that day I was on a train heading south. As soon as I arrived at Albatross I had to put my gear into an office and jump onto a bus to be driven back to Sydney with the rest of the contingent and begin three weeks of very intensive training for Vietnam.

I think we all felt like pin cushions, both arms jabbed with a load of vaccinations, including for the Plague.

At an army training area in Putty Mountain I was dragged from bed about 3 am and taken to headquarters to examine a patient with appendicitis. It was night and there was heavy fog making it very dangerous to land a helicopter. The question I was asked was, could we wait until daylight or risk the chopper. I said wait and loaded the patient up with antibiotics. Everything turned out just right.

For a year from October 1967 I was part of the first contingent of the Royal Australian Navy Helicopter Flight in Vietnam, led by Lieutenant Commander, later Admiral, Neil Ralph.

The contingent consisted of:

· Thirteen Officers; (two of whom were killed in action);

· Two Chief Petty Officers;

· Eight Petty Officers, (one killed in action) ;

· Sixteen Leading Ranks; and

· Eleven Able Ranks.

I was the only medically trained person in this group and responsible for their health and medical welfare.

This contingent, plus about eighty American Army troops, formed the 135th Assault Helicopter Company under the command of Lieutenant Colonel R. M. Cory USA.

Arriving in Vung Tau meant some adjustment as the Americans sorted out our rank and duties.

Early on there was a parade where I considered a request to grow a beard. No chance. We were working with the Americans, I was told, and they did not approve of beards. A Chief Petty Officer asked if we could grow a mustache, like the Americans. The answer was no because we were RAN.

I worked in the sick bay of 222nd Aviation Battalion Medical Detachment, 54th Aviation Company, treating many out-patient conditions, but mostly venereal disease. And keeping up with our sailors’ inoculations.

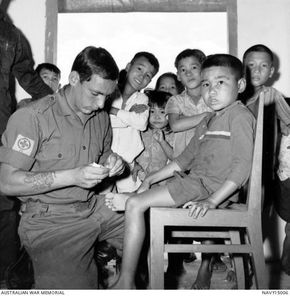

I would also regularly go to a Catholic Mission in a nearby refugee camp where the US Army photographed me treating children. Apparently, this was a public relations exercise.

Came the day when Commander Ralph asked me for the names of all his officers who were treated for venereal disease, infected during our stopover in Manila. We stood toe to toe, he demanding names, as ship's captain, and me refusing on grounds of medical privacy. It was very tense but he didn't get the names. (I found out later in Australia that I was supposed to give them to him).

We were given an early Christmas Dinner as we were being transferred from Vung Tau. We didn’t know where we were going until we heard Saigon Rose on the radio telling us when and where we were going, and how we were all going to be killed on the way.

The transfer was to a remote jungle camp known as Blackhorse, a forward command post of the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment.

On the way to Blackhorse, I had to travel in the fire engine. The driver and passenger section had no roof or sides so was fully open to the weather. The extreme dust thrown up by the convoy meant that I had to ride facing backwards with wrappings around my mouth and nose. It doesn’t sound much but try travelling all day like that.

On arrival, I found that I had no sickbay, medical supplies or equipment and nobody willing to give me any information.

We lived surrounded by roads with ankle-deep bulldust. The next few days were spent on that fire engine, filling up with water and hosing down the roads around our part of the camp, trying to lay down the bull-dust, which got into everything, including the food.

On the second day at this, the driver and I were at the dam sitting in the hot sun getting sleepy as pumps filled the tanks with water. Then enemy mortar exploded around. Some landed in the little dam. Off we went up the road, dragging our hoses. Had the driver not reacted so quickly when we heard the mortars we would have been at least wounded.

I was responsible for all of the 135th assault company, but our Battalion was based at Binh Hoa and because of the distance and the road is heavily mined every day and night, it was not possible to use the medical facilities at headquarters, All I had was a first aid bag.

But on finding there was a hospital in our camp I went visiting, and soon made friends with the doctors of the 68th Medical Group 7th Surgical Hospital. With their donations of furniture, equipment and supplies I was able to set up my sickbay. So I held the sick parade, arranged for lab and x-ray appointments, performed minor surgery, gave inoculations, changed dressings and kept all medical records.

The only problem was when I did this Commander Ralph ordered me to remain at the sick bay 24 hours a day saying that because of the medicines I had in stock, he was concerned for their security.

I was only allowed to leave the Sick Bay for meals and a shower, and then only if I had someone to guard the tent. Weeks later two American Medics were assigned to help me.

The commander of the Americans’ hospital accepted my offer of help. I worked in his operating rooms, sometimes for seventeen to eighteen hours a day.

Going to the hospital, I had to pass a prisoner of war compound, with its tent roof open sides enclosed by several fences of wire and barbed wire, I saw many prisoners on the way, but none when returning. It wasn’t a good feeling for I had heard stories of them being dropped from a helicopter or tied to tank tracks and squashed, I had seen photos of prisoners buried up to their necks in our defense perimeters and used for target practice. I asked an American soldier boiling a large can of water outside his tent and creating a terrible stench, when he dipped in his stick and pulled up the skull of an enemy soldier, saying it would make a great lamp base. I mentioned this to the head doctors and a priest, only to be told that it was a common occurrence and if men could take out their hate on a dead enemy it was healthier than to keep it locked inside, and I should not be concerned.

The TV series and film MASH capture scenes when wounded troops are brought in, but they could not express the smell, the sounds of the injured screaming, and the flow of blood, or the feelings you have when you had to leave wounded men unattended, as they were labelled DEAD. When we finished with the others we would return to the DEAD and try to save those still breathing. War injuries are the most horrifying of all and only those who have been there will know what I am talking about.

Another time I was riding shotgun in a semi-trailer traveling to Binh Hoa to pick up a portable building for a recreational room. Officially we were not to have one, but I agreed that the men needed to have a place where they could relax while not flying missions. And I needed to paint the latrines to help prevent scabies being spread. Along the way, a farmer picked up a rifle and fired a shot at us. The bullet went through the windscreen between the driver and me. We took off. We still did our bartering at Binh Hoa, returning with a full flat pack of Recreation Room.

Several of my patients had to be treated for `crabs’. I believed one of the sources was our block of lavatories, long sections of unpainted thunder boxes, where the timber was cracking. I was denied permission to get paint because we were a temporary camp and not entitled to paint the toilets.

Through bartering, I got what was needed and painted the lavatory seats, solving the problem. The officers’ toilets remained unpainted, but I seem to remember most of them started to use ours.

Sometime later headquarters sent two doctors and ten medics to do the work I was doing, so because of an extreme shortage of people, I went to work as a gunner on the smoke ship, that is a helicopter which travels at about 90 miles per hour, six inches off the ground, laying a smoke screen so that other helicopters could pick up troops safely. The gunner I replaced was brought in with his knee smashed from hitting a tree branch. He couldn’t be replaced for a few weeks and it was said that Smokey would have to be grounded until a replacement gunner arrived I volunteered because I felt that it would be part of rescuing many troops.

Another time, while in the PX (shop) I heard a gunshot but thought nothing of it, because the sound of gunfire went on all the time. A GI grabbed me and said I was needed outside because a soldier had been shot. When I got to him I was told that his friend had shot him. I thought the bullet had gone through his mouth and out his ear. I felt a pulse then lost it, so I started resuscitation and told the onlookers to get an ambulance. I continued the resuscitation into the hospital. The doctors pronounced him dead after they tried to revive him. The bullet entered just above his top lip, never came out just scrambled his brains. When I went to clean up I saw in the mirror my whole face, hands, neck and hair caked with blood.

When the enemy moved on the Blackhorse hospital was not so busy, so I moved to Xuan Loc Hospital, which had one surgeon working up to twenty hours every day. The workload meant I operated using local anesthetic, many amputations of legs and arms (the limbs were already half off as result of mines).

Our barracks were hit by mortar several times, I yet somehow there were no casualties that I know of.

Returning from taking a patient from surgery to the ward one night, the doctor and I were walking back to the operating theater by way of a short covered path between the two buildings when we were fired upon by a lone gunman with a machine gun. The doctor was ahead of me and able to get into the building. I was trapped in the pathway with bullets all around me. It seemed like forever, but the South Vietnamese soldiers found the attacker and located him and shot him up pretty badly. Next day I spent over two hours treating his wounds. I was told that he was required to be questioned.

Our patients were all civilians with all kinds of war injuries, mostly from land mines, but we also did all kinds of general surgery, from lancing and draining infected breasts to caesarean births.

Perhaps the saddest cases were little girls who survived being thrown under the wheels of army convoys by their parents to try to get cash compensation. One girl had a thigh de-gloved of skin. The hospital had no skin grafting knives, we tried pinch grafts but they failed. The hospital at Blackhorse at first they refused to accept a civilian patient, but because of my work with Doctor Darrell A. Jaques, the boss, he made an exception and the girl was successfully treated.

And so to the barely believable ugliness: I sit at the bar of the Blue Angel, having a beer with some mates. In comes a large Afro-American. He walks up to a bar-girl, pulls out his .45 handgun and shoots her dead. We didn’t hang around for long but found out later he avenged his best friend, who had married just before shipping out to Vietnam. He apparently had sex with the bar-girl who wore a circle of razor blades in her vagina. He penetrated once and when he withdrew, his penis was sliced into threads. The hospital had to amputate.

The blades were mounted on a short tube-like structure, much like a shutter on a camera. I was shown one. The penis could enter easily

But the danger was withdrawal. I was told that every prostitute and business person had to pay tax to the Viet Cong, and that some girls, but not many, were given these contraptions if they didn't have the money to pay.

Because most of the work in the sick bay at Vung Tau was treating Venereal Disease, I found where the Australians commonly visited and with the permission and advice of Army doctors and of the Mamma San, I gave free regular penicillin injections to the girls. They said that the mandatory inspections by the Vietnamese doctor cost them a lot of money and consisted of the doctor just looking at their genitals.

-------------

When I returned from Vietnam I was working back at HMAS Penguin Operating Theaters, Vietnam was never again mentioned by anyone until 1970 when I had been transferred to the submarine depot HMAS Platypus. Again I was the only medically trained person at that establishment.

About 30years later I was awarded Door Gunner Wings.

During that stay, I was asked to volunteer to go to sea in a submarine. A doctor was preferred but they couldn’t get one to volunteer. They asked me because of my Vietnam experience, telling me I was needed because if the sub had been detected it could come under attack. The expedition turned out to be for sixteen days, fourteen under water. I was required to perform all duties on board as well as my medical ones. One of the crew took sick within the first few days and I had to decide whether we continued the mission. We went on.

I retired from the RAN on the 30 June 1970, after completing my term of enlistment of nine years, during which I not only trained as a Sick Berth Attendant specializing as a Operating Theater Technician, but I was also a certified Ships’ Diver.

Submitted 11 January 2022 by Mahendra Thomas Francis Blackman