ORTON, Alfred George

| Service Number: | F2951 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | 1 April 1940 |

| Last Rank: | Able Seaman |

| Last Unit: | Not yet discovered |

| Born: | Subiaco, Western Australia, 16 November 1915 |

| Home Town: | North Beach, Stirling, Western Australia |

| Schooling: | Not yet discovered |

| Occupation: | Merchant Seaman |

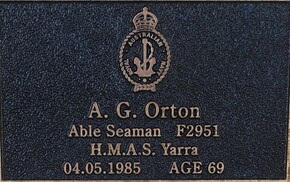

| Died: | Perth, Western Australia, 4 May 1985, aged 69 years, cause of death not yet discovered |

| Cemetery: | Not yet discovered |

| Memorials: | North Beach Wall of Remembrance |

World War 2 Service

| 1 Apr 1940: | Enlisted Royal Australian Navy, Able Seaman, F2951 | |

|---|---|---|

| 24 Dec 1943: | Discharged Royal Australian Navy, Able Seaman, F2951 |

Help us honour Alfred George Orton's service by contributing information, stories, and images so that they can be preserved for future generations.

Add my storyBiography contributed by Brian Jennings

Alfred George ORTON

The Listening Post Autumn 1986

An Unsung Hero's Five Days of Hell On Water

By MIKE SOUTHWELL Reprinted Courtesy of the Western Mail

HISTORY has credited the sinking of the HMAS Yarra with few words. It went down in one of the many battles between the Japanese and Allied forces for control of the Java and Coral seas. George Odgers' “The Royal Australian Navy - An Illustrated History” devotes two paragraphs to the human consequences of the sinking. "Of the ship's complement of 151, a total of 138 went down with the ship or died later on the rafts.

The 13 survivors were picked up five days later by a Dutch submarine. But one of those survivors - West Australian Alf Orton - was haunted by the awful memory of those five days for the remaining 43 years of his life. Just before he died, Alf decided it was time to tell the story the historians had ignored. He called his memoirs “Survivors at Sea” and began them with the words, "I will try to convey to the reader what happened to the men on the rafts and the terrible ordeal they went through."

A Survivors Story

West Australian Alfred George Orton, one of only 13 survivors of the HMAS Yarra, decided to write his memoir after being told he had terminal lung cancer early in 1985. · He died in May 1985 aged 68. Orton gave the eight type-written pages to his friend Charles (Todd) Marsden only weeks before his death, with the simple instruction: "See if you can get this published somewhere." Marsden said that Orton had often been urged to write about his ordeal but refused because he thought it would be distressing for the families of those who died when the Yarra was sunk or were lost from the life-rafts. He describes his friend as a simple gentleman who, after leaving the navy, always lived near the sea and loved to go fishing.

Marsden believes it was Orton’s physical strength and self-control that enabled him to survive for five days on a raft.

He then gives details of HMAS Yarra's service from the time it left Fremantle on August 28, 1940, with Leading Seaman Alfred George Orton on board until its sinking in the Timor Sea on March 4, 1942. ·

The Yarra's last duty was to escort a convoy of seven ships from Jakarta to Darwin. Five days out, the drama- began. As Alf Orton tells it:

On breaking daylight we were confronted by a task force of three cruisers and four destroyers coming at us fast. Our captain immediately laid a smoke screen to protect the convoy and ordered ships to scatter in. all directions. We were soon under heavy fire as the Japs had us circled. We were taking so many hits that it was only a matter of time. We were being blown to pieces and the Captain gave the order to abandon ship. I left my gun and proceeded to my station post Carly Raft, which lay at a 45 degree angle on a chute with a wire rope connected to a slip. I slipped the raft and with. superhuman strength landed it over the side: I proceeded to the starboard side and slipped the other raft over. I then made it back to my gun to report to Commander Smith that the rafts were over the side. My life jacket was already blown away and then, there was a terrible surge of air and noise and I was blown over the side. When I came to, the Yarra was on her port side, with the twin screws still turning. A tin of biscuits floated passed and I managed to grab it. I had lost my boots, a sock, a glove and half my overalls, and I was bleeding from the nose and ears. I made it to one of the rafts, put the tin of biscuits aboard and hooked my 'arm through the life ropes. There were a lot of wounded people in the water and we gently lifted them on to the raft and continued to hold on for our lives. The Japs then circled us looking for officers, but we were all dressed in the same battle station rig. A large cruiser came along-side and I'll never forget looking up at the Jap sailors grinning down at us. The cruiser made a 160 degree turn, swamping the rafts in its wake. We righted them and scrambled back, losing quite a few men in the incident. The rafts and a plank that had drifted off the timber rack were filled to capacity and we were all up to our necks in the sea. We spent the first day silent and dejected. We had not had a decent sleep since the fall of Singapore and, having no food, we were not in a very good position to survive what lay ahead of us. We lost men that day as some were too weak to hang on and we were powerless to help them. You'd be surprised at the number of sailors who can't swim.

The sun was very hot and we were relieved when it went down. But we shivered that night and waves were continually breaking over our heads. That night we lost 26 men and prayed for the sun to come up,·as we were chilled to the bone. When it eventually did, to our horror, we were surrounded . by. sharks. Huge brutes they were, continually circling us but not attacking. Only when we lost a man over the side would we look away. It is in such predicaments that men turn to religion. The Catholics on the rafts crossed themselves continually. The worst time for shark attacks is dusk. That evening, as the sun went down, they came in to attack. One would make a pass and then the others followed. That night they tore away the men hanging over the sides. All we could do was smash the water with paddies. We lost another 14 men. After that terrible night we faced a new day in rafts more buoyant because of the loss of so many men.

I learnt that I was the leading seaman aboard and had to get some routine going if we were to survive. At 9 o'clock, by my reckoning, I thought it appropriate to say the prayer we all know in the navy. So I got all men to hang their heads while I conducted a service in what was a very strange place indeed. "'Protect us from the violence of the enemy (which He did) and the raging seas, so that we may return to the land, and enjoy the fruits of our labour. Amen!" A rating then asked where I thought we were and I lied and said not far from Darwin. I said that if we kept paddling south we would make it as patrol boats from Darwin would be looking for us. This settled a few of them down and gave them heart. But the truth was we were 250 miles from the nearest land. We were now into our third day, and it was starting to play on us all, some worse than others. The terrible sun was beating down on us. We had no water and the tin of biscuits had drifted away in the rough seas. Some ratings started to drink-salt water and some held their heads under. I told them to stop, but when I wasn't looking they'd do it again.

We were attacked again that night by the sharks and lost more men. There were 17 on our raft, with none over the sides. But we were still up to our necks in water. By this time we had no water or food for five days and the men were throwing salt water on their faces and eating seaweed as 1t drifted passed. There were now only 13 of us left and 1 tore strips off my life jacket and passed them to the men to suck on to keep the saliva going in their mouths.. We ate rubber, buttons, our singlets and seaweed, but the privation was taking its toll.

We were burnt black by the sun and froze at night. We cursed the sun coming up and we cursed it going down. We cursed the sharks, the sea snakes and the insects that bit us all night. By this time we were unable to talk, only croak. We sat at a 45 degree angle·on the raft and hugged each other for warmth at night, and got a few hours sleep. Some of the things that happened on the raft are painful to record but I think it is my duty to do so. One rating stood up in the raft and said he could see his wife in the distance and was going over the side to meet her. He swam away and I ordered the men to look in the opposite direction.

When a warship enters harbour the first man ashore is the duty postman. One man asked us if we had any letters to post as he was going ashore to get the mail. He then swam away. Another rating confided in me that there was a cellar full of food under the raft. When it got dark he was going down to get some and share it with me. I couldn't convince him it wasn't true and we never saw him again. I am really convinced that the rating saw his wife, the postie felt his duty was to go ashore and the rating had his cellar full of food under the raft.

By this time we had stopped paddling as all our strength was gone. Our buttocks were red raw with the chafing of the canvas raft and covered with huge saltwater ulcers. It was agony to move. All we could do was stare at the endless ocean. We all had our visions. l used to see a spit post sticking out of the sea. It is clear to this day. I looked for it one day just before sundown, and sure enough it was there. I told the other men: It seems different this evening. Then I saw it move. It wasn't a spit post. It was the conning tower of a submarine coming towards us. I stripped off my half overalls and hung them from a paddle. The men held me while l waved.

The submarine circled us and I could see the officers scanning us with binoculars. It must have been obvious from our emaciated appearances that we were shipwrecked sailors. They came alongside the raft and threw a rope. One by one I put it round the ratings and the sailors (they were Dutch) heaved them on to the submarine. I was the last to go but those stupid Dutch sailors - curse them and bless them - pulled me off as the raft was under water. Like the christening of a ship, I hit my head on the side of the submarine. Bloody hell, with all I had been through. now I had a bump on my head: I don't remember them carrying me into the submarine.

The submarine took Orton and the 12 other survivors to a hospital in Ceylon. After recuperating they were taken back to Fremantle. Orton later served in the merchant navy.