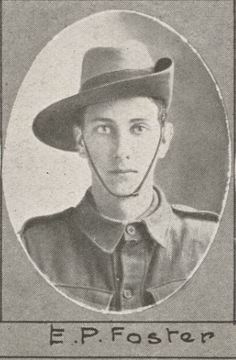

FOSTER, Edwin Peter

| Service Numbers: | 536, NX113726, N23070, NX113726, NX113726 (N23070) |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | 9 July 1915, Enlisted at Brisbane, QLD |

| Last Rank: | Lieutenant Colonel |

| Last Unit: | 41st Infantry Battalion |

| Born: | Rousemill, New South Wales, Australia, 30 January 1897 |

| Home Town: | Rous Mill, Ballina, New South Wales |

| Schooling: | Not yet discovered |

| Occupation: | Farmer |

| Died: | New South Wales, Australia , 1983, cause of death not yet discovered |

| Cemetery: | Not yet discovered |

| Memorials: | Rous Mill Honour Board |

World War 1 Service

| 9 Jul 1915: | Enlisted AIF WW1, Private, 536, 31st Infantry Battalion, Enlisted at Brisbane, QLD | |

|---|---|---|

| 9 Nov 1915: | Involvement Private, 536, 31st Infantry Battalion, --- :embarkation_roll: roll_number: '16' embarkation_place: Melbourne embarkation_ship: HMAT Wandilla embarkation_ship_number: A62 public_note: '' | |

| 9 Nov 1915: | Embarked Private, 536, 31st Infantry Battalion, HMAT Wandilla, Melbourne | |

| 27 Jun 1916: | Promoted AIF WW1, Corporal, 31st Infantry Battalion, In France | |

| 1 Jan 1917: | Promoted AIF WW1, Lance Sergeant, 31st Infantry Battalion | |

| 16 Mar 1917: | Wounded AIF WW1, Lance Sergeant, 536, 31st Infantry Battalion, Gunshot wound to the left thigh and evacuated to England on 21 March 1917 aboard HS Gloucester Castle. | |

| 8 Aug 1918: | Honoured Distinguished Conduct Medal, Work near Warfusee-Abancourt on 8 August 1918. Citation reads: For conspicuous gallantry and able leadership when his company was temporarily checked by direct fire from a field battery. He did excellent work in rallying the men and working them forward. After reaching the final objective he cleared the ground for several hundred yards in advance, inflicting severe casualties on the enemy. His example was eagerly followed by his men.London Gazette on 5 December 1918, page 14459, position 5: Commonwealth of Australia Gazette on 14 March 1919, page 423, position 2 | |

| 4 Jan 1919: | Promoted AIF WW1, Second Lieutenant, 31st Infantry Battalion | |

| 4 Apr 1919: | Promoted AIF WW1, Lieutenant, 31st Infantry Battalion | |

| 16 Mar 1920: | Discharged AIF WW1, Lieutenant, 31st Infantry Battalion, Discharged at the 1st Military District |

World War 2 Service

| 21 Jun 1942: | Enlisted NX113726, N23070, 41st Infantry Battalion, Enlisted at Bobs Farm, NSW | |

|---|---|---|

| 21 Jun 1942: | Enlisted Australian Military Forces (WW2) , Lieutenant Colonel, NX113726 | |

| 12 Jun 1944: | Discharged NX113726 (N23070), 41st Infantry Battalion, Rank of Lieutenant Colonel |

Edwin Peter Foster

Edwin came from Rous Mill near Lismore on the Richmond River in the Northern Rivers District where his parents ran a store. He was the second child and eldest son of Frederick Edwin Foster and his wife Constance Evelyn nee Snodgrass. He attended the local primary school and worked on his father’s farm. He had thoughts of becoming a teacher but when things looked grim at Anzac Cove, he enlisted in Brisbane on 9 Jul 1915 for what became a varied military career which eventually extended to the command of the 19th Infantry Battalion in New Guinea during World War 2. On enlistment, he gave his occupation as farmer and was single at the time. He stood six feet two inches tall, weighed 150 pounds and had 6/6 vision in each eye. He is described as having a fresh complexion, grey eyes and light brown hair.

He was assigned to B Coy 31st Battalion at Rifle Range Camp, Enoggera on 11 Oct 1915 after initial training. His spell there was fairly brief and soon after he was sent to Broadmeadows Camp, Melbourne where the 31st Battalion was preparing to move overseas. There his training was continued along with the rest of his battalion and his CO, Lt Col Frederick W Toll VD, was especially concerned that his men should be able to salute properly, at the proper time and saluting the proper people. He was also very keen to make sure that no one had hair longer than half an inch growing on his head. There were the usual difficulties finding equipment and uniforms for the men but eventually they were considered well trained enough to out-salute the King’s enemies.

On Tuesday 9 Nov 1915, they breakfasted at 0530. There were two trains to take them to the waterfront, the first to depart at 0724 carrying B Coy, including Edwin. From the railway station, they marched to Town Pier, Port Melbourne and boarded HMAT Wandilla A62 at 1245. Altogether, 30 officers and 961 ORs of the battalion and one officer and 100 ORs of the 1st Reinforcements sailed that day and while we cannot be sure in which group Edwin found himself, since he had been allocated to B Coy, it is reasonably sure he was a member of the battalion.

The ship arrived in Fremantle at 1100 on 15 Nov and left again at 1200 but nevertheless, six men managed to desert in Fremantle. The battalion arrived in Suez at 1300 on 6 Dec after an uneventful voyage and disembarked at 0730 the next day. There was some sickness among the men for 35 required hospitalisation on arrival. The rest of the battalion entrained for Heliopolis with the last of their trains arriving there at 1700. They were accommodated in Camp Zeitoun while another six men were hospitalised. Thirty-four men of the 1st Reinforcements were transferred to the battalion to make up for those lost to sickness and desertion. I ought to thank the officer completing the diary for his contribution through the unusual clarity of his handwriting. He even went to the trouble of printing names of places and some people in block capitals, a worthy practice I wish all the others had adopted.

The men were allowed a little time to recover from their voyage but on 13 Dec they entrained for Ein Gosshein, west of Serapeum, near the centre point of the Suez Canal. They marched into Camp Serapeum the next day and there, they lost their first casualty, Pte H Trulson who died in hospital of cerebrospinal meningitis. He was only the first though and the battalion lost more men as time went on.

They celebrated Christmas at Serapeum, a dusty, windswept, solitary place but on 3 Jan 1916, they relieved the 29th Battalion in guarding the Suez Canal against Turkish attacks. B Coy went to Serapeum East. They stayed there till 31 Jan when the 29th Battalion came back to relieve them. Not much happened during that period but the men must have been rather bored there with nothing to do except keep a lookout for a notional enemy attack which never happened. Half the battalion was still on guard duty but A and B Coys were training hard particularly at musketry. It was not until 23 Feb that the remainder of the battalion was relieved and rejoined the other two companies in camp, just in time to leave on 24 Feb for Tel-el-Kibir. At 0425 on 24 Feb, the first train departed to be followed at 1030 by the remainder. The transport arrangements were not at all to the CO’s liking and he was quick to point the finger at the railway department. The carriages provided were merely horse trucks, only just evacuated by the horses and in a deplorable state. Nevertheless, the train got them to Tel-el-Kibir during the afternoon. Their allocated campsite was as filthy as the trains but the CO soon had men cleaning up and pitching camp. There were sufficient tents to have 10 men per Bell tent rather than the usual 14 so there was more room for everyone. They settled into camp, all 34 officers and 975 ORs, as by now, some of the sick men had recovered and rejoined the battalion.

Through the first three weeks of March 1916, the battalion lost men to other units while a certain amount of reorganization was en train. On 3 Mar though, Edwin fell ill with influenza and was admitted to 15th Field Ambulance at Moascar. He was there for only a few days and returned to the battalion on 6 Mar, hale and hearty. On 22 Mar, he was part of the parade that was inspected by the Prince of Wales, who was trying to find something useful to do but never found it to his dying day. The next morning, the battalion trekked out to the station and boarded three trains for Ferry Post, the first leaving at 0750, the next at 1405 and the final one at 1545. They camped near Ferry Post where they spent a day or two settling in. They were ordered to a new position five miles east on 28 Mar and moved another thousand yards northeast where they settled down again to guard the Canal. They christened it Duntroon Camp from where they relieved the New Zealand Mounted Rifles on guard duty. At the end of March 1916, the battalion was reduced in size by the depredations of the reorganisations to 23 officers and 726 ORs.

The advent of April brought reinforcements though, 145 in all. On 14 Apr, the 53rd Battalion relieved them of their guard duty and they filed back to Ferry Post from Duntroon Camp to join up with the rest of the 8th Brigade. Here we find them conducting the first remembrance service of the anniversary of the landing at Anzac Cove. It was remembered as Anzac Day and declared a general holiday. But once they recovered from their unaccustomed holiday, they went for a nice route march on 29 Apr. They did many of them in the course of their training which also included an emphasis on bayonet fighting and night operations. And the CO was unimpressed by the failure of the system to keep up a sufficient supply of arms and equipment. Their training continued into May but on 28 May, the whole of the 8th Brigade trudged to Moascar, starting out on their four mile march at 0448 (sic).

After a fortnight in Moascar, they entrained for Alexandria at 2100 on 15 Jun 1916, and after a long and uncomfortable train ride, they arrived next morning at 0600. The following day, they boarded HMT Hororata at 0700 and sailed for Marseilles in convoy, escorted by a light cruiser. Another uneventful voyage completed, they landed at Hangar No 7 at Marseilles at 2015 on 22 Jun 1916. They overnighted there and the next day, entrained at 1015 but did not depart for the north until 2245, a very long and boring wait no doubt. The trip was very slow and tiring for it took the best part of three days to cover the distance to Steenbecque where they arrived at 0820 on 26 Jun. From the station, they marched to Morbecque, near Hazebrouck, where they were billeted ‘very satisfactorily’. After all the parties of the battalion reached Morbecque, they had 30 officers and 983 ORs on strength at the end of June 1916.

At Morbecque, they had their first experience with poisonous gas with the whole battalion being given a practical demonstration of its use and effects. Then, wasting little time, they were ordered to march to Estaires via Merville and so left Morbecque on 8 Jul 1916. The next morning, they left Estaires for Rue Dormoire, about one mile west of Erquinghem, where they relieved the 18th Battalion in the reserve area behind the front lines. Two days later, on 11 Jul, the battalion relieved the 15th Battalion, taking over part of the line in the Bois Grenier sector. This was their first experience in the front line trenches and must have been a very trying experience for inexperienced men in a new unit. From here they retired to Fleurbaix on 16 Jul being relieved by the 4th New Zealand Battalion. That day, they had their first battle casualties with nine men being wounded by enemy shelling. The next day brought more with another 14 men being wounded by shelling. It was no better on 18 Jul when another 12 men suffered the same fate. Artillery fire was the major cause of casualties on both sides on the Western Front.

On 19 Jul 1916, four weeks after their arrival in France and with only three days experience in the front lines, they attacked across no-mans-land at 1800 with the 32nd Battalion, another unit of the 8th Brigade, on their left and the 54th Battalion, 14th Brigade, on the right. The Battle of Fromelles was their cruel introduction to full scale warfare, western front style. Despite fierce enemy shelling, they gained their initial objectives and tried to consolidate their positions during the night. But the forces on their flanks were driven back the next day and so they too were forced to withdraw to their starting point, but many fewer men came back than started the day before. The losses among officers and NCOs were very high indeed which lead to confusion among the men as their leaders fell. It was not a totally edifying picture that the CO painted after the battle in his report to the brigade commander. While praising the actions of many men, he nevertheless noted that some had to be forced at gun point to hold their positions as they were close to panic, especially when they saw others around them on their flanks fleeing. He also noted that the intelligence picture of German positions was very poor since some areas thought to be trenches were actually waterlogged drainage ditches.

The battalion lost 77 men killed, 414 wounded and 85 missing, a total of 576, more than half of the total strength of the battalion. Losses on this scale were completely devastating, especially for untried troops however well they might have been trained. Many of the losses happened before the attack was launched when the Germans bombarded their forming up positions. Friendly fire accounted for a lot of casualties too for in the lead up to the assault, the barrage had fallen short in many places, contributing to the battalion’s heavy casualties. The quality of maps was very poor and the men on the ground often did not know where they were or indeed where they were expected to be. The artillery, in the absence of real information, relied on estimates which were highly inaccurate. Thus many shells fell on friendly troops. For example, of the eight signalers who were organised to be runners in case of a breakdown in communications, six were put out of action before the attack went in. During the attack, Edwin’s B Coy was to be in the third and fourth waves, two platoons in each, so perhaps he had a better chance of survival than the men in the first two waves. In the event, casualties were so high that the CO ordered the third and fourth waves to attack together. Edwin was fortunate in coming through without injury and was doubly fortunate in that the losses among the NCOs needed to be replaced. His standing was sufficiently high for him to be promoted to Corporal on 26 Jul as one of the replacements for men lost in the battle.

After the battle, the battalion trudged to Bac St Maur where they were billeted. They received some reinforcements on 23 Jul but their strength was still only 11 officers and 501 ORs after that. A very big hole had been blown in the battalion. But this was only the start for them for the war had a long way to run. While they were trying to reconstitute the battalion, they moved their position to Rue Biaches where the billets were congested and extremely dirty.

The rest of July was spent reorganising and recuperating after the severe turmoil of the July battle. But by 1 Aug, the battalion was considered fit again for front line service and so it trekked back into the line to relieve the 29th Battalion. They were allotted a quieter sector of the line so that they could continue to recover from the disastrous losses of Fromelles. After two weeks there, they were withdrawn to billets in Rue Biaches and they were employed as labourers in the front lines working to improve their defences. Hard and heavy though it was, their casualties were few and the terrors of Fromelles much ameliorated. They were employed in this fashion for a fortnight and on 29 Aug they tramped at 0530 to Bois des Vaches near La Motte. Here they were billeted and rested while their training continued. At that time, the battalion had 27 officers and 552 ORs on strength, a far cry from the thousand men who had arrived in France.

They received specialist training in ‘wood fighting’ in the expectation that they would soon find themselves engaging the enemy in wooded country rather than in the siege warfare they had so far encountered. Their day started with bayonet fighting training at 0700 for half an hour. Breakfast followed and at 0930, there were various lectures, company exercises and the obligatory route marches, all aimed at improving their knowledge and capacity to perform well in fighting in the woods. They were taught the northern hemisphere’s bushcraft, especially the likely direction branches of particular types of trees would be pointing. For instance, the French forest was said to harbour a large, rough barked tree like the Australian Hickory in colour and growth, the main boughs of which pointed south or south southwest. They were taught to blaze trees to mark their paths but unfortunately they were not allowed to actually mark any trees in any way so this particular bit of training was limited to the theoretical only. French susceptibilities were more important than realistic training apparently. Fortunately, the French did not object to their being issued with a new gas mask, the Small Box Respirator, which was apparently an improvement on the previous device. They were trained to use it, army style of course, by numbers, five in all, complete with coming to attention at the end of step three. One can be sure the CO insisted on that.

Naturally, during this training, it rained which had some effect on the training but the CO was pleased with the results nonetheless. Their training completed, they marched out at 0930 on 7 Sep 1916 to Fleurbaix. Initially, they marched in column of route with a five minute interval between companies, to Merville then Sailly. But when they reached Sailly Church, they moved in platoons, in single file at 100 yards intervals between platoons. Their billets were in such a filthy state that the CO demanded that a staff officer witness the mess before his men took over. They stayed in Fleurbaix till 21 Sep, training and resting before moving to Armentieres. They slogged there in single file in sections, one third of a platoon, at 50 paces interval, keeping well to the right of the road. They strode along the Rue da Biach and the Rue da Biere after which they formed up in companies and marched along the main Erquinghem – Armentieres road to their billets. The next day, they took over a section of the line at Houplines in front of Armentieres from the 4th Battalion, the Seaforth Highlanders. They stayed there for a week during which all was very quiet in their sector. On 28 Sep, the battalion was withdrawn to the third line, the reserve trenches, behind the segment of front they had been holding. At the end of the month, their strength had increased to 34 officers and 749 ORs, not back to their original strength, but much better than it was in the aftermath of Fromelles.

After a short rest in the reserve trenches, the battalion moved forward to the frontline on 4 Oct occupying a position on the left of the Houplines sector. Although this sector was relatively quiet, the battalion launched a trench raid on 12 Oct which captured three prisoners and some equipment. The next day, they were relieved and marched out of the trenches for Strazeele and were carried there by motor bus once they had cleared the danger zone. After a few more days’ rest, they marched again, this time to Bailleul where they entrained for Long Pre where they arrived at 1415. At 1515, they were on the march again, this time for a point on the Abbeville – Moufleurs road from where they were bussed to Buire, arriving at 1750 and going into billets. The next morning, they were off again, starting at 0845 for Nametz Woods where they camped on the slope of a hill under canvas. The next morning, 22 Oct 1916, they trooped to Montauban where one company took over a part of the line from the Liverpool Regiment. Next day, the battalion took over a section of the front line called Factory Corner from the 29th Battalion.

During this time, we hear nothing of casualties yet it would be rare for a unit doing the sort of duty the 31st had been doing not to have any at all. Almost certainly, there would have been some but their numbers are not mentioned at all in the War Diary.

On 28 Oct, the battalion was relieved by the 32nd Battalion and they retired to billets in Montauban Camp. The break was short lived and they swapped again with the 32nd on 31 Oct, taking up the defence of the Factory House sector. On 4 Nov, they were relieved again, going back to Montauban Camp from where they trekked at 1245 the next day via Mametz to Eastcourt Camp. On 6 Nov, they were again on the road, this time to Buire via Albert. On the next afternoon, they were bussed to St Vaast-en-Chaussee for some rest and recuperation. Over the next ten days, they trained hard and got themselves back into fighting trim. In that period, Edwin was granted some leave from 12 Nov but the record does not make it clear the period of his leave. Probably a week or ten days was the most to be expected though. Then, at 0805 on 18 Nov 1916, they were bussed to Ribemont where they were billeted. At 1130 the next morning, they trudged to Mametz Camp where they stayed overnight but filed out again the next morning to another camp to the west of Trones Wood. At 1500 the next afternoon, they relieved the Guards Brigade in the front line. Short and quiet though their stay was, they were probably quite happy to be relieved on 23 Nov and to move back to Montauban Camp. From there however, they were employed for the rest of the month on labouring duties in Bernafay Wood and Trones Wood, not actually the type of work their ‘wood fighting’ had prepared them for though.

Into December 1916, they carried, dug and built around the camp area and into the front lines. More reinforcements arrived too and occasionally, they sent small parties to reinforce units holding the front lines. We hear of some shelling of their positions and work areas but no casualties are noted. Their labours continued until 20 Dec 1916 when they swapped their picks and shovels for rifles and packs and marched out at 0830 for the railway station at Quarry Siding where they entrained. The train left at 1030 and arrived at Meaulte at noon from where they trekked to Dernancourt but they found their billets very dirty. They were allowed a few days’ rest there to clean up and then began more training.

Christmas Day was celebrated with Church Parade and a march past, followed by an afternoon holiday. There is no mention of other celebrations, but if they were running true to form, the men would have been provided at least with a good dinner. And a nice Christmas present was delivered to the men on 27 Dec when they all had a visit to the baths, the first one recorded in the unit diary since they left Australia, and they all got new underclothes and sox. Probably, they had not been having too bad a time as far as baths were concerned until recently and this is why it drew the comment, but we cannot be certain.

At the end of 1916, the battalion had 32 officer and 807 ORs on strength but only 22 officers and 708 ORs were with the battalion, the remainder being on detached duty or in hospital. One of those absent was the CO, Lt Col Toll, whose health had been deteriorating for some time.

New Years Day 1917 was memorable for two reasons, General Birdwood gave the men a holiday and Edwin was promoted to Temporary Sergeant vice Sgt GD Bridgland who had been evacuated sick. While the first event made it into the diary, the second did not though we find a new hand in the diary who chose good printing as a suitable recording method, which I applaud. I hope he enjoyed a good route march too because they were about to get some more practice. On 3 Jan 916, at 0900, they marched out via Buire and Heilly to Franvillers where they arrived at midday and went into billets. At 0900 the next morning, they trudged to Cardonette via La Houssoye, Pont Noyelles and Querrieu, arriving at 1230. Here, they recommenced their training and received a new CO; Major Davies was promoted to Lt Col and give command.

The battalion’s marching qualities were tested again on 13 Jan when they were ordered to return to La Houssoye where they were billeted. The next morning, the 8th Brigade, having been concentrated together, marched to Dernancourt. More marching ensued on 15 Jan when they all tramped out to Montauban Camp, a three hour march, a place they must have been very familiar with by now. However, on arrival, the incumbent battalion refused to leave till 1430 so the men sat down by the roadside and ate a hot meal from the cookers, washed down with a nice hot cup of tea. The discussion between the two COs has not been recorded unfortunately. Most of the battalion marched out the next day at 1330 to the intermediate line, the second line of trenches often referred to as the support trenches or line, while B Coy remained in Trones Wood. By 1815, they had relieved the 21st Battalion and prepared to move further forward the next evening to the front line. Again, their front line duty was brief and they retired on the night of 20 Jan back to the reserve line. The next day, they moved back to camp in Trones Wood and on the day following, to Montauban Camp again. They must have been feeling unwanted in the front line as they had nothing much to do since the Fromelles attack. But if they were anxious to do more time at the front, they had some time to wait. In the meantime, they went back to labouring for the rest of the month.

In fact, they provided fatigue parties for the first week in February too and not until the morning of 7 Feb did they move out for Fricourt, a short march away. Not much changed except the location though and the work and training continued. Finally, on 14 Feb, they marched for Delville Wood at 0900, arriving there at 1215. They moved up to the reserve line the next morning early, at 0515. Then on 19 Feb, the battalion moved into the front line again in front of Delville Wood and took over from the 32nd battalion. Lt Col Toll returned and took over from Lt Col Davies who left to command the 55th Battalion. The weather at this stage was appalling. It was a very cold winter and just keeping warm was a struggle. But now the rain had turned the flat country into a quagmire in which men got stuck and had to be pulled out by their comrades. Sometimes the mud froze and paradoxically, made conditions better but only marginally. No one on either side was enjoying the conditions.

Unlike all the other diaries I have read, this one tells us nothing much at all about the daily routine, the shelling, the casualties, the weather even. It is principally a travelogue of their movements and not much more. But at this point of time, we start to hear a little of what was happening. We hear of shelling though not its effects, patrolling without any results and the hard physical work that always went on to keep defences prepared but without specifics.

This tour of duty did not last very long either, the battalion being relieved on 23 Feb and plodding back to the Reserve line. The next evening, they completed the move out of the line with most of the battalion, except for a working party of 100 men, back in Trones Wood. The working party arrived at 0100 the next morning. While they were in the front line, the men wore gum boots and were issued with hot drinks twice a day which must have helped a little to make conditions better for a brief while at least. They had not finished marching around yet though. On 26 Feb, they slogged back to that well remembered camp at Montauban, arriving in nice time for lunch. At the end of February, the battalion had 38 officers and 922 ORs on the roll but only 29 officers and 643 ORs were with the unit, the remainder being on detached duty or in hospital.

They must have felt like a tennis ball actually for they no sooner settled in Montauban Camp when they were ordered back to Trones Wood, to which they repaired in obedience on 2 Mar 1917. Three days later they were ordered to march back to Montauban Camp. The staff officers clearly were having a fine war. But the 31st Battalion was not. However, they recommenced their training which proceeded normally until 11 Mar when they were again ordered to move, this time to the Fleurs sector. Here, by 2045, they had taken over from the 18th Battalion in the reserve line. The next evening, they moved into a section of the front line near Thilloy and Le Barque and began patrolling to their front in the direction of Bapaume. Their role was to drive the enemy out of Bapaume. All patrols met strong resistence and heavy machine gun fire. They sent out patrols again the next morning which also met heavy fire and were shelled into the bargain as they went forward along the line of the Beaulencourt road. This is the first time we start to get a real picture of their doings in the front line though I wish my friend the printer still had his secretarial job.

On 13 Mar, forward patrols of the battalion moved into the Brickfields area and occupied a position there that the Germans had vacated. They also moved into the Grevilliers line and Warlencourt trench and were the first allied troops to enter the defences of Bapaume. At about 1130, the HQ moved forward to Le Barque in order to maintain better control and communications with its companies. While the forward companies kept up the pressure on the Germans, they showed no sign of retiring further and put up a very strong resistence employing many machine guns and heavy artillery. A patrol of eight men was stopped from entering Till Trench and five of the men became casualties but they managed to erect a bombing stop, an improvised wall across the trench to stop the Germans getting close enough to throw grenades.

Sometime during this day, Edwin suffered a gun shot wound to the left thigh and was admitted to the 6th Australian Field Ambulance which was then located at Bazentin le Petit. Three days later after his initial treatment, he was transferred to the 1/1 Midlands Casualty Clearing Station at Chocques, about 75 km east of Etaples, where he was cared for for another three days. Then he was transferred by ambulance train to Rouen and thence to the 11th Stationary Hospital. Evidently, his wound was quite serious and it was decided that he ought to be evacuated to the UK for further treatment. On 21 Mar, he was again moved, this time to Le Havre where he was loaded on to the Hospital Ship Gloucester Castle for England. The next day, he was admitted to the 1st Southern General Hospital in Edgbaston, Birmingham. It was 2 Apr before his father was told he had been wounded and 4 Apr before he learned of its nature. He seems to have recovered quite well for he was granted leave on 20 Apr till 5 May. On that later date, he returned from leave and reported to the Training Depot at Pelham Downs in the UK. He might not have been fully recovered though for he reported sick and was admitted to the 1st Auxiliary Hospital at Harefield. He apparently improved enough to be discharged on 19 May when he was transferred to No 4 Command Depot at Wareham near Weymouth on the south coast. Here he recuperated and also underwent further training. But it was not all plain sailing. On 29 Jun 1917, he was tried before a District Court Martial the charge being: At Wareham, on 2 Jun 17, without reasonable excuse, allowing to escape a person committed to his charge. He pleaded not guilty but was found guilty anyway. He was awarded a loss of seniority in the rank of Corporal and forfeited 28 days’ pay while he was in custody. However, it was later determined that he had been charged under the wrong rank, ie Corporal, rather than his correct rank which was Sergeant. The forfeiture of pay stood but the loss of seniority seems never to have been resolved as there is no further reference to it in his documents. The court martial does not seem to have had much impact on his subsequent career though.

He remained at Wareham until 31 Aug 1917, recuperating and training, but on that date, he returned to duty at the Overseas Training Brigade at Codford, about 25 km northwest of Salisbury, on the windswept Salisbury Plain. This brigade trained troops due to go to the front in the latest techniques and weapons for trench warfare and was designed to give them the final polish before sending them to the front. Edwin though was not sent directly to the front. Instead he went to No 5 Group at Hurdcott, a few kilometres north of Salisbury on 14 Sep 1917. He was there till mid November and therefore missed the Battle of Polygon Wood in which his battalion played a very significant role. No 5 Group was composed of the 14th and 15th Training Battalions and the Pioneer Training Battalion. As Edwin was a Sergeant with front line experience, he may well have been sent to the Group as an instructor since it is doubtful if he would have gained much from further training himself.

On 15 Nov 1917, he proceeded to France via Southampton from the Training Battalion’s camp at Longbridge Deverill where part of No 5 Group was stationed. He arrived next day at Le Havre where he marched in to the 5th Australian Divisional Base Depot. After a few days there doing the paperwork and final kitting out, he marched out to the 31st Battalion on 19 Nov and finally, after the usual terrible train journey, arrived back at his unit on 22 Nov 1917. His friends would have been fewer then because of their duties after he was wounded. They had had a very hard time of it indeed.

During the day he was wounded, 13 Mar 1917, the battalion managed to push the line 1100 yards forward. Still, they had not moved as far forward as planned mostly because the enemy barbed wire was still effective since it had not been cut by the artillery. Another factor was the mud which made movement very difficult for the attackers and for their supply echelons bringing up ammunition and rations. By the morning of 16 Mar, the men of the unit were quite exhausted and it was considered advisable to relieve them immediately. Thus the 30th Battalion moved in that day and the 31st moved out by 0100 on the 17th, having made considerable territorial gains. But these came at the cost of 14 dead, 336 wounded and a further 69 evacuated, probably sick.

The battalion was held in reserve at Factory Corner for a time but on 18 Mar, it moved to positions in Thilloy, Rye Trench and Luisenhof Farm from where it was employed on the familiar duty of labouring. Meanwhile, the Australians had captured Bapaume and it was to that town that the battalion next moved on 21 Mar 1917. Here the front line was merely a few holes in the ground and so the men were digging trenches in order to link up these holes to form a continuous defensive line. These measures were continued for the next few days until 26 Mar when GHQ ordered them forward as reinforcements for a section of the line near Fremicourt which they reached around 1100 and where they were held in reserve. But the situation improved and they were withdrawn at 1750 to a line of outposts in Bapaume. The next day, the battalion moved to Le Bucquiere via Bancourt and Haplincourt and took over the front line from the 57th Battalion around Beaumetz. B Coy was positioned in the centre of their line with A Coy on their right and C Coy in reserve. Overnight, they were shelled severely and at 0130 on 30 Mar, they were relieved and withdrew to Bapaume leaving A Coy holding the Bancourt line. The next day they received orders to move up the line in front of Beaumetz. On 1 Apr 1917, they left Bapaume at 1515 and moved forward through Bancourt, Fremicourt and Lequcouiere to the front line forward of Beaumetz, completing their move by 2225 and relieving the 53rd Battalion.

The next day, the 55th and 56th Battalions launched an assault against Doignies which they captured. The 31st provided flank support on the right for the attack and had five men wounded in the action. At 0100 on 5 Apr, they were relieved by the 53rd Battalion and moved back to Bancourt. For the next nine days, they went back to labouring, building huts, working on roads and the myriad tasks an army requires to do in such large scale operations. At 0815 on 15 Apr 1917, the battalion again slogged forward and took up positions in the outpost line in front of Bapaume. Here they stayed and found the sector quiet but were relieved on 21 Apr by English troops of the 33rd Brigade. They were ordered to return to Montauban, their old stamping ground, which they reached by 1800 having marched via Beaulencourt, Gueudecourt, Flers and Delville. They were allowed some rest, but mostly they worked and trained until 9 May. By now, their strength had risen to 41 officers and 1010 ORs but leaving aside those detached and hospitalised, there were 33 officers and 823 ORs effectively on strength.

The original orders for 9 May were cancelled and in their place, the battalion was instructed to march to the line between Beugny and Ytres which they reached at 1915. By this time, the practice of sending a nucleus of the battalion to the rear while the main force went to the front had become fairly standard and so back to Bancourt went a proportion of the battalion. At 0815 on 11 May, the battalion moved up the line and relieved the 2/11th London Rifles, all being completed by 2230. Their position was in the reserve line in the Lagnicourt sector near Bullecourt. Edwin with B Coy was stationed along the road between Morchies and Lagnicourt. At this stage, this sector was relatively quiet although artillery was active on both sides. They were shelled by the Germans but were reasonably well dug in. On 15 May, B and C Coys were shelled heavily with gas shells but their new gas masks were effective. They were still being used as a labour corps though and worked in tunnels and in building strong points for defence. On 18 May, the battalion received packages of chocolates, biscuits and cigarettes from the YMCA which were distributed among the men and probably gratefully received as there were few things to be happy about in their very strained lives.

Their positions though remained very quiet, by western front standards, right through to moving forward to relieving the 29th Battalion on the night of 20 May. They were in place by 0125 the next morning and began patrolling straight away. Enemy shelling continued in a more or less desultory fashion every day but occasionally it was more fierce, such as on 24 May when two men were killed and more were wounded. Later that night, they were relieved by the 10th Rifle Brigade which was completed by 0200 the next morning. They marched to Bapaume later in the day where they bathed and rested. The rather parochial nature of the Australian force was pointed up by the arrival for comfort packages just for the men from Ballarat, a reminder that the battalion had a lot of Victorian men as well as Queenslanders in its ranks. On 30 May, they moved camp to Senlis, near the Reservoir northeast of Bapaume. Through this period, they were training and working and resting when they could. On the last day of the month, their blankets were deloused, a helpful but temporary action against the lice that plagued everyone at the front.

June started with a nice short route march, a mere five miles to brush away the cobwebs and get back to real soldiering rather than the savage nightmare of trench warfare. The next day it was back to work digging trenches and conducting training. And so the month plodded on, route marches, hours of spade and pick work and more training. Occasionally it rained but the routine went on regardless. They even managed to get paid on 19 Jun but there was not much around to spend it on locally although about one in ten men was granted leave to go to Amiens to sample the delights of French provincial life. On 23 Jun, they managed another bath and, wonder of wonders, they had another one on 30 Jun, a mere week apart. What the CO thought of this spoiling of his men, I shudder to think. The last day of the month was so wet that training had to be cancelled. If only the war could be cancelled so easily.

The routine continued into July although with an occasional variant. On 3 Jul for instance the good Archdeacon Ward delivered to them his well-travelled talk on VD. They probably enjoyed that more that the tactical night march they started at 1815 that afternoon. They were to bivouac for the night away from camp and recommence their march at 0300 the following morning. Unfortunately, a thunderstorm prevented their marching at that hour so they tramped back to their billets instead, arriving at 0500. This not training in the wet does seem a very strange approach for an army which was called upon to fight in the most appalling weather but I expect the men were grateful nonetheless. I suppose the general reason was that there was so much sickness in the ranks that was weather related, it was foolish to court more by additional exposure to the elements if it could be avoided.

Still the routine lumbered forward but on 8 Jul 1917, B and C Coys were ordered to march to Thiepval Wood some 16 km from Bapaume for field firing practice, a bit further than usual and not very popular because it entailed a night away in bivouac. The training, work and some rest periods continued till 29 Jul, a very long break away from the front, when they were ordered to join the Second Army along with the rest of the 5th Australian Division. They entrained at Aveluy Station on 30 Jul and their train (No 10) departed at 0742 (sic) for St Omer and then they plodded to billets in the Racquinghem area, finally reaching that town at 2210. The troops were very pampered with clean box trucks while the officers had to make do with proper passenger coaches. There were 30 box trucks for 893 ORs and two coaches for 38 officers. Now, while the box trucks might seem somewhat crowded, they were very well ventilated indeed having many gaps in their floors and sides, possibly even in the roof too.

There is an unusual entry for 1 Aug 1917 in the war diary; ‘Court of Enquiry assembled to enquire into the fate of certain officers and other ranks.’ Many men of the battalion went missing during the operation around Fleurbaix during 19-21 Jul 1917. In all, in that action, two officers and forty-three ORs were missing, about five percent of the men engaged. Such enquiries were not uncommon on the western front where, because of the conditions under which the men were fighting, many disappeared without trace. All eight who were the subject of this enquiry were presumed dead even though their precise circumstances were unknown. On the same day, three officers and 96 ORs arrived as replacements for men who were no longer with the battalion. The meat grinder needed to be fed.

The weather was wet and miserable for several days but it did not prevent a route march every second day. On 10 Jul, they tramped off to Blaringhem for a bath and clean clothes and then trudged back again, rather undoing the good work done in the baths. The whole of July was occupied in training in tactics, musketry, gas reaction, signaling, judging distance, sniping, bombing, fire control, scouting and of course marching. They trained as sections, platoons, companies, as a battalion and a brigade. After 16 weeks of intensive training, they were very well prepared for their military tasks.

At 0925 on 16 Sep 1917, the battalion formed up for the march of 16 miles to Steenvoorde. It was a dry, windy day, not at all comfortable for marching since a constant cloud of dust formed around them. The roads were largely paved with cobblestones and deeply rutted making marching very difficult, with heavy traffic not helping at all. They reached their billets at 1800, very tired and dusty. But they were off again the next morning by 1030 for the forward area but only had to cover a mere seven miles, though it was showery. They camped under canvas in the area around Wippenhoek. Nearby, a model of the terrain around Hooge, Polygon de Zonnebeke and Gheluvelt had been built to acquaint the men with the area they were to attack and capture. All ranks spent several days contemplating the model to understand exactly what they were required to do. On 24 Sep, the battalion marched from Wippenhoek at 1725 to the Chateau Segard area, arriving there at about 2000, in front of their target, Polygon Wood. At 2200 the next night, they filed out for the front line. The men were in good spirits and the diary records that 25 men who were rostered for leave in the UK refused their leave, choosing to stay with their comrades for the attack. In all, 21 officers and 689 ORs worked their way towards Polygon Wood.

The 31st Battalion was tasked with following up the leading 59th Battalion, who were to take the first (Red Line) objectives, and together with the 29th Battalion, they were capture the second line, the Blue Line objectives. They formed up near Black Watch Corner, but were delayed by traffic and other difficulties and only arrived about ten minutes before zero hour. They were to form the right flank of the brigade’s front with the Royal Welch Fusiliers (RWF) on their right. The attack got off to a muddled start and the 59th eventually went forward with the 31st and 29th Battalions. The attack came under intense machine gun fire from four of the enemy’s guns which caused many casualties. This machine gun group was attacked and eliminated but at that point, it became clear that the Royal Welch Fusiliers had not made good their attack which should have taken those guns. The right flank was therefore unprotected. Indeed, the reserve company of the 31st reported that many of the men from the RWF were scurrying back. As their flank was very vulnerable, the men in the forward positions were ordered to withdraw and on rejoining the battalion HQ in the Red Line, the whole retired to the vicinity of Black Watch Corner because it was not possible to hold a position so exposed on its flank.

In an interesting peek into the social mores of the time, while they were in reserve, they were ordered ‘to bury all the dead officers and as many men as possible’. Not much could be achieved though because of the intensity of the enemy shelling. The many casualties soon overpowered the available medical services and some of the wounded were untended for 48 hours, which, added to the shelling, must have been nearly unendurable. The battalion diary contains copies of messages between the various officers of the battalion as the action developed. When one thinks of the conditions under which these messages were written, one can only marvel at the calmness and self-control of the men writing them. Here is one to represent many, written by the adjutant and sent to brigade HQ:

“Urgently require water and ammunition. Reports re location do not agree. Am making every effort to reorganise to carry out order. Units are mixed and many casualties amongst officers make position difficult. The whole right flank is under heavy enfilading machine gun fire. Enemy’s shell fire fairly heavy.”

The picture is succinct but clear. A lot of officers were down making control of the battalion very difficult. They needed water and ammunition. Their right flank was in a perilous position and, making allowance for some restrained understatement, the German artillery was making life very difficult and for many, impossible. It could not go on and that was recognised up the command chain because they were ordered to withdraw. The attack was called a success because a small amount of territory and arms of the enemy were captured but the goals of the operation had not been reached. For the second time, the 31st Battalion had performed magnificently but suffered enormously for it. Edwin was very lucky indeed to miss it.

On 29 Sep, the remnants of the battalion withdrew from the support lines back to the Chateau Segard area. They needed a much smaller camp this time for only six officers and 271 ORs returned. Total casualties were eight officers and 76 ORs killed, four more men had died of their wounds, seven officers and 305 ORs were wounded and 33 ORs were unaccounted for. The total casualties were 15 officers and 418 ORs. The CO recommended 31 men in all for decorations ranging from the VC to Mentions in Despatches. The next day, they staggered back to Café Belge where they camped and were able to visit the baths. And then they started to rebuild the battalion again.

At 1300 on 1 Oct 1917, the survivors of the battle trudged from Café Belge to Connaught Camp near Wippenhoek, arriving there at 1630. The weather was very warm and the roads of course very dusty making the march, for over-tired men, very arduous indeed. It was not until 5 Oct that that the CO had the heart to commence training his men again as they were in such poor shape after the battle and needed rest. And to get them back into the right frame of mind, he gave a route march on the afternoon of the 5th. The weather grew cold and wet but the war ground on, and on 8 Oct, they embussed for the Chateau Segard area at 0640 and arrived at the new camp at 1100. The next day, they plodded forward to relieve the 7th Battalion in front of Chateau Segard, moving via Derby Road, Warrington Road, Birr Crossroads, Bellewarde sleeper track, Harris duckwalk and Helles Track. Their position was on the Broodseinde – Noorendhoek Road between Romulus Wood and Remus Wood. The weather was fine but the German artillery distracted their minds from the climatic conditions.

Early the next morning, 10 Oct, they had a box seat for a battle between British and German aircraft overhead with the Germans retiring. The weather was changing considerably now with dull, cold days and showers and even hail. So the men were not unduly disturbed when they were relieved on 13 Oct by the 57th Battalion and retraced their steps back to their billets near Chateau Segard. The area was renamed Swan Area and the next day, they moved to Ouderdom Camp, departing at 1359 and arriving at the new site at 1600. Here they were allowed another rest but only for a few days. On 17 Oct, the trekked forward to the support lines but the next day were sent back to the camp at Ouderdom, which they reached, marching through the rain and over roads which were getting very boggy already. Here they rested till 21 Oct, watching the cold rain turning the roads, such as they were, into mud and probably dreading having to try to slog through it soon. The order came on 21 Oct. They started out at 1530 through the rain to the front line and eventually were able to relieve the 56th Battalion which left the line by 2120. But the German shelling on the way in killed two men and wounded eight more making it a bad start indeed in this position called Halfway House near Broodseinde Ridge. Over the succeeding days, the diary paints a picture we recognise as typical of the Western Front, rain, mud, shells, sleeplessness and hard work. Then on 26 Oct, they were relieved and moved out at 1300, or rather staggered out, to Vancouver Camp through the rain and mud and over roads which were extremely congested. In Halifax Area in Vancouver Camp, the nucleus group rejoined the battalion and everyone had a few days’ rest, even having a hot bath on 27 Oct. But the weather stayed wet and cold while they worked hard at reorganizing themselves and preparing for future operations. Training recommenced on 29 Oct and on 31 Oct, joy of joys, they had another hot bath and were given clean underclothes. Two baths in four days was a record.

In their two stints in the line during October, they lost 23 men killed, nine more died of wounds and 69 were wounded, although 13 of them stayed on duty. They had lost many more at Polygon Wood but the cumulative losses were diluting the experience levels among officers and men alike and the reinforcements needed a lot of training before they could be real replacements for the men lost. At the end of October, the battalion had 38 officers and 876 ORs on strength but after allowing for those elsewhere, there were only 30 officers and 669 ORs, many of them newly joined.

The first few days of November were spent in training, some of it in the rain of course, but it also brought a typewriter and a typist. Your scribe blessed both for their clarity. And also the diarist at this time thought it acceptable to give more details of their activities and so we find for the first time, quite a lot of information about their doings. On 5 Nov 1917, the battalion marched out for the Wippenhoek area moving via Ouderdom, Reninghelst and Connaught Camp. They completed the march around 0045 the next morning even though the night was fair and the road mostly dried out. Their new camp was very muddy and there was much effort expended to make useable tracks in the camp area. Here they trained for a few days but on 11 Nov 1917, they moved out at 0811 (sic) to Locre where they were billeted in Doncaster Camp which they reached at 1120. They filed out again the next morning at 1115 for Neuve Eglise, a mere half an hour away. Here they were comfortably quartered in huts and farmhouses. In fine but cold weather, they recommenced their training, and route marching of course. On 14 Nov, they moved out at 1400 to march to Canteen Corner Camp, some 45 minutes away, where they were again comfortably housed. They must have outlived their welcome there too very quickly for on 16 Nov, they were ordered to move to Pioneer Camp about two hours march away. Training went on there but on 21 Nov, the battalion was ordered to relieve the 30th Battalion in the reserve line in the Warneton sector in front of Messines. The next day, Edwin rejoined his battalion after an eight month break. There may have been some familiar faces but many of the men would have been strangers to him.

Here they did the usual things expected of them, reinforced their positions, patrolled no-mans-land, sheltered from enemy artillery fire, lost plenty of sleep and tried to stay alive. The only bright point was that they received clean sox each day and a hot meal each night which must have been a real luxury indeed. Although this was a relatively quiet sector, there were still two men killed and five wounded by the end of the month.

December brought snow, wind and very cold weather so the men were issued with sheepskin vests and woollen gloves as protection against the elements. There was plenty of work in fetching and carrying, improving fortifications and accommodation as well as cleaning up and salving. The Germans thought it worth their while to send over balloons with propaganda pamphlets in English and French but their effect on front line troops was negligible except that the paper could be a very useful product in some circumstances. On 7 Dec, they were ordered forward to relieve units in the forward line near Bethleem Farm just east of Wulverghem. They began moving up at 1530 and were all in place by 0225 the next morning, a move achieved without casualties. They settled in to their new digs but the enemy were intent on making it as difficult as possible for them and shelled their positions continually. They noticed that one area was being blasted at a time and then another, gradually working across the whole of their front from many directions. Enemy air activity was kept to a minimum by allied aircraft though.

It rained on 9 Dec causing flooding of the trenches and making the ground boggy and hard to traverse. Nevertheless, the battalion sent out patrols to find out where the enemy was and what he was up to. These went out each night, either a reconnaissance one or a fighting patrol whose task was to capture enemy soldiers for questioning. Shelling was an almost constant feature of trench life and while it waxed and waned in its intensity, it was always a danger. The weather too was changeable and a spell of fine weather made things more bearable. Relief came on 17 Dec when the battalion tramped out of their positions at midday to a railway siding at Dekennebak where they had a hot lunch and entrained. The train departed at 1500 for a long, cold journey to Desvres where they arrived at 0200 the next morning and moved into comfortable billets. They spent the rest of a very cold day settling in.

Their occupation of the line cost the lives of two men and another 11 were wounded, light casualties comparatively but tragic at any time. For several days, they rested, cleaned and reorganised. On 21 Dec, they began training again in the morning but had organised games in the afternoon. A holiday atmosphere had begun to build up as a recreation room was set up, with writing materials, periodicals and games. A piano was available for anyone that way inclined and free hot coffee and biscuits were there for the asking. Church parades were held on 23 Dec and the next day was declared a holiday for it was market day in the village. Men were able to buy, doubtless at inflated prices, whatever took their fancy, and indeed one man bought a small pig, whether as pet or pork is not recorded. Rations for Christmas day were issued on a sumptuous scale, including half a pound of plum pudding per man. Everyone got a new pair of sox too but some of the comforts that had been arranged from the UK had not arrived and the CO was apologetic to his men for this disappointment. Christmas Day itself started with the battalion band playing Christmas carols around the town and camp. Christmas dinner consisted of roast beef and vegetables and plum pudding, washed down with a bottle of beer per man. All was found very acceptable. Boxing day was also a holiday, marked with a large scale snowball fight through the town.

Work started again in earnest on 27 Dec, training in the mornings till 1300 and then rest or games according to the weather. It was still very cold and miserable weather, slushy ground and muddy paths making movements unpleasant. Church parades were cancelled on 30 Dec except for the Catholics who went ahead anyway. And the next day, the officers saw the old year out with a dinner to which they invited the GOC of the brigade. At year’s end, the battalion had a total of 45 officers and 1023 ORs on strength but only 31 officers and 909 ORs were actually with the battalion as the others were on detached duties.

The new year opened with football matches and another holiday. On 2 Jan, a photograph was taken of the whole battalion after which another round of football was enjoyed. Possibly some even enjoyed the next day’s route march over seven and a half miles of frozen tracks. For those with energy left, there was rugby in the afternoon to play or watch. The camp routine of training and recreation was well established and even though the weather often defeated the game players in the afternoons, training went on except when conditions were too cold or snowy. On 9 Jan, blizzard conditions engulfed the camp, indeed it was fierce weather across the whole area. The next morning brought warmer weather, relatively speaking, sparking a thaw which refroze making the surface glassy and dangerous. Commonsense prevailed and the planned route march was cancelled in favour of a snowball fight masquerading as a practice attack on a defended position. They apparently learned a new lesson, that lots of snowballs could hold up a flanking attack. On 11 Jan, they bathed and were issued with clean underclothes.

The routine went on; training in the morning and in the afternoon, sports. There was even a cross-country race, in full kit, over 1,000 yards of hilly country. The battalion’s team ran fourth but the diary writer, an able diplomat, does not tell us how many teams competed. But if each battalion in the brigade was represented, fourth would have been equated with last. They did better in the Lewis gun competition, being first in accuracy but ran second in the time test. 14 Jan was declared a sports day for the battalion but it was still very cold. On 17 Jan, the weather, in the shape of strong wind and rain, again conspired to defeat a proposed route march, much to everyone’s disappointment to be sure.

The general routine continued until 30 Jan 1918 when they were ordered to move to the Messines sector. They left camp at 0335 and trekked to Samer, some eight kilometers distant which they reached at 0600. However, the railways being what railways are, there was a long delay in moving out and not until 1245 did the trains leave. Further disruption was caused later on and they were forced to stop at De Kennebec and walk to billets at Neuve Eglise which they reached about 2000. The next afternoon, they trudged out at 1430 via Wulverghem to Lumm Park to relieve the 10th Battalion and took up their positions in the line between Wambeek on the left and Blauwepoortbeek on the right. While the battalion’s nominal strength was 40 officers and 1013 ORs, only 30 officers and 598 ORs went into the line, the remainder going with the nucleus or to other duties. A Coy were in the front line, B Coy in the support line and C and D Coys were in the reserve lines.

Patrolling commenced immediately but no enemy was seen. In fact it was very quiet. A fog descended the next morning which was cold and frosty. On 2 Feb, the sun made a brief appearance but the enemy artillery did not. A few enemy machine guns fired on them but only managed to wound one man. The mist hung around even though the sun shone weakly but the enemy was very quiet and even Allied artillery fire could not provoke him into responding in kind. One bright spot bloomed though; the padre managed to collect cigarettes for the men in the line and they were very well received, having become very scarce. On 4 Feb, they rotated companies, Edwin, with B Coy, moving into the front line.

Each night, they sent out patrols and wiring parties but saw nothing of the Germans. But on 8 Feb, a patrol captured one man, a Lance Corporal of the 5th Coy 163rd Infantry Regiment. Enemy shelling was very light and work and patrolling went on. Companies changed posts again on 8 Feb, B Coy moving back into reserve. But soon, one day merged into the next, so much was the same that they were hard to differentiate. Dawn stand-to, breakfast (of a sort), work, lunch, more work, dinner, patrolling, all with shelling interspersed, enemy aircraft overhead, machine guns chattering and the everlasting winter soaking everything in rain and cold. Occasionally, men were hit as they moved about in the nighttime. On 21 Feb, two were wounded while moving towards the German trenches when they were spotted by the enemy.

Close behind the reserve lines were the battalion canteen and a YMCA group which provided hot cocoa at all hours. But fortunately, the battalion was relieved on 21 Feb by the 59th Battalion and they moved back to the Kemmel area where they were billeted in huts in Rossignol Camp. The change brought little rest though as the battalion provided working parties for carrying duties to the front line units. The weather improved for short periods but was still quite cold. By the end of February, the battalion numbered 42 officers and 1020 ORs but allowing for detached men, only 32 officers and 744 ORs were available on strength. But February had brought wounds to eleven men and death to one more.

March began with timber cutting, trench digging and a boxing competition. The weather turned appalling again, rain, hail, wind and biting cold formed the miserable atmosphere in which they trained and worked. By 6 Mar, it was classified fine and mild, with everyone hoping it would stay that way. The usual routine of ‘resting’ battalions was adopted, training and some sports. But their ‘rest’ ended on 15 Mar when they filed out of camp at 0630 and moved via Yarra Track back to Lumm Farm. Here they relieved the 59th Battalion and by 2145, all companies had completed their move and were well established. No casualties had been sustained in the move. They held the Wambeek Spur, with the 32nd on their right and the 29th on their left and facing them, their old friends of the 163rd Infantry Regiment. They were welcomed by the enemy artillery too with a fairly heavy pounding until 0130 the next morning.

Patrolling of course went on nightly and on 17 Mar, one patrol found a satchel attached to a deflated balloon containing what purported to be the dispositions of German units. These papers were forwarded to higher headquarters. Another patrol of three men ran headlong into a party of Germans and in a short fight all three were wounded but the enemy did not pursue them in their retirement. One of them had to be evacuated. It seemed that the enemy was about to launch a large scale raid on the Australian positions and that the chance encounter had first delayed it then caused it to be withdrawn. The weather was improving, almost, and one or two days were what Victorians call fine and sunny. On the night of 25 Mar, the 18th Battalion relieved the 31st, the changeover being completed by 2200 without loss. They moved back to Rossignol Camp via Yarra Track and Gordon Road where they spent the night. At 1000 the next morning, they moved by bus to a point near Godewaersvelde driving through Abele along a road which was under long range artillery fire from the enemy. Fortunately, though shells were bursting close to the road, they got past without mishap. From there they slogged to billets in Fontaine Houck and were comfortably housed in barns and farm houses. Their peripatetic existence showed no sign of stopping for the next afternoon at 1545 they were sent back to Godewaersvelde where they arrived at 1745. Here they boarded a train at 1845 and after a record short wait, they moved off at 1915 for Doullens. Clearly, something was in the air.

They arrived at their destination at 0735 the following morning and moved by route march via Authieule, Amplier, Orville, Thievres, Authie and Bus les Artois to Bertrancourt where they arrived at 1615 after a trek of some 20 km. The roads were very dusty, making marching very uncomfortable. Ironically, heavy rain fell soon after they arrived at their billets and continued through the night. On 29 Mar, the men were woken very early and marched out at 0830, passing through Louvencourt to Vauchelles where they camped for the night. The next morning they moved off at 0845, straight back to Louvencourt. One begins to see the extent of the dislocation of planning caused by the German Michael offensive against the Fifth Army further south. But they stayed in Louvencourt this time.

During March, the battalion had lost six men killed, three more dying of wounds and 13 wounded. There were 41 officers and 979 ORs on strength although only 24 officers and 776 ORs were available, the others being elsewhere. Their new station at Louvencourt was about 110 km south of Rossignol much closer to Amiens, some 32 km away, and much closer to the scene of the German breakthrough. It seems they were being held as a reserve against any further German advances. Their position was between the German advanced positions and the vital Channel ports which the British had to hold at all costs or face defeat. Without them, their supply position would have become unmanageable. From the diary though, one would not guess that this was the position for it records nothing abnormal at all and one supposes that they were almost oblivious to the real circumstances of their movements. Perhaps they drew some conclusions from being ordered to place picquets to protect the southern and southeastern approaches to the town. Or possibly from their intense training in open warfare and rapid bolt manipulation for loading their rifles, needed to deal with infantry attacks. In any case, they settled down to their training regime with the weather as changeable as ever.

They were ordered to move on 4 Apr 1918 and at 1845, they marched to the busses along the Louvencourt – Vauchelles-les-Authie Road. By 2015, they were on their way to Daours. Over the bumpy roads they drove, arriving at Daours at 0230 the next morning and were moving into billets there when they were ordered to march at once to Bois de Gentiles, only a few kilometers north of Villers Bretonneux . They set off at 0335 and marched through the rest of a very long night to reach Bois de Gentiles at 0700 where they bivouacked. After a few days here, on 8 Apr, they were directed to move to Aubigny and two hours later, at 1815, they tramped towards that town. Here they relieved the remnants of the 43rd Brigade, an English unit, in the reserve area. They were let into the strategic picture at this point and were told that the GOC intended to hold that line Hangard to Corbie against expected German attacks. On 9 Apr, they marched to Corbie and then along the north bank of the Somme where they relieved the 15th Battalion overnight. By 0210 the next morning, the relief was completed without casualties. Their front lay between the Somme and the Vaire-Hamel Road, B Coy holding the left sector away from the river. In between was the town of Bouzincourt which the Germans subjected to frequent heavy shelling. During the day, one particularly vicious bout of shelling caused 27 casualties when three shells fell on a farm which some of the battalion were occupying.

German artillery fire was being quite active and many casualties were being inflicted by it. Patrolling went on regardless but very little was heard or seen of the enemy soldiers. While there was considerable movement behind the German lines, apart from the artillery, there was little evidence of any Germans in the vicinity at all. A lot of work was done improving the positions and digging and wiring became the order of the day. Each night, the battalion sent out patrols but little of any account was found. On 15 Apr, the Germans tried their hand at patrolling but ran into an Australian outpost which fired on them, forcing them to withdraw. Both sides had aircraft overhead during the day but little seemed to happen.

Patrolling and watching were the norm although of course, enemy artillery did its best to disrupt things. The patrols found little of interest though and watching was difficult in the often misty weather. On 26 Apr, the men had a piece of luck. Someone found four large tubs in the village and provided them for bathing. So 12 men from each company were able to bath and even be issued with clean singlets and sox, all of which was a distinct boon to tired and verminous men. Over succeeding days, most of the men were given the same treatment. A barber was found too and much needed haircuts were handed out freely. To the end of April, it remained quiet except for the artillery. Even so, 21 men were killed and five more died of their wounds. Another 38 were wounded.

May began in the same fashion, lots of activity but no progress, many patrols but nothing to report, more baths but they all got dirty again. On 10 May, a British aeroplane was shot down over them and crash-landed in no-mans-land. Two men from the battalion went to the pilot’s aid and rescued him, almost uninjured, and brought him back safely to the battalion’s position. The shelling continued but neither side was in any hurry to try to take the positions of the other. This was a real stalemate with both sides recovering their breath after the March offensive. Occasionally, things went wrong and a patrol was caught up in a serious fight. On 25 May, three men were killed and seven were wounded when a large party was seen by the Germans who fired on them. The party retired bring the wounded with them. May was just like April, no serious action but casualties were incurred nevertheless. Four men were killed in May, two more died of wounds and 42 were wounded. At the end of the month, there were 26 officers and 645 ORs in the line with the battalion, another 11 officers and 150 ORs were stationed with the nucleus and the remainder were away on other duties, principally in hospital or at courses.

The quiet routine was brought to a close by the order to withdraw and hand over to the 50th Battalion. On the night of 1 Jun 1918, the battalion withdrew in good order and without casualties and by 0130 the next morning, they were marching towards Aubigny where they camped in trenches and dugouts. The next morning, after they were relieved in this position by the 14th Battalion, they trudged out again at 0825 for Rivery where they arrived, very tired and dirty at 1245. They took over billets in the Hospice area and cleaned up and rested. They had been in the line for 53 days continuously, believed to be a record for the Allied army. They were fortunate that no major action had developed during this period but even so, the intense stress of trench life on the front line would have been all but overwhelming. Small wonder that many men had such great problems coping with life after the war.

The men started to relax and for several days, there was little military activity as they rested and reorganised. The brigade band was available and their music seems to have been very much appreciated. On 5 Jun, training recommenced along the usual lines, training in the morning, sports and games in the afternoon. On 6 and 7 Jun, everyone was inoculated and given two days no duties to recover. Those fit enough to take part, played sports. That day, the 32nd Battalion moved out of the camp which allowed the 31st to spread themselves out quite satisfactorily. Right through this period the weather was fine and warm, something the men no doubt appreciated very much. On 9 Jun, a Sunday, after the voluntary Church Parade, the battalion held an aquatic carnival as a try out for the brigade carnival to be held on 12 Jun. It was held in the baths at Amiens and included swimming and diving. We do not know the results but it was well attended and enjoyed by everyone, even though there was enemy shelling nearby in the centre of Amiens.

It rained the next night but only enough to lay the dust. The higher authorities were worried that having so many men in the small cluster of buildings at the Hospice might induce the Germans to shell it, with the chance of great casualties. So efforts were made to find somewhere else for the battalion to camp. On 11 Jun, they marched from the Hospice to Camon where they were billeted in trenches and tents, far less comfortable that the huts at the Hospice but much less vulnerable to German shelling. They took some comfort too in the continuation of fine and warm weather. Their training continued the next morning and in the afternoon, the brigade aquatic carnival was held and accounted a great success with several of the battalion’s men winning their events, including something called a cigarette race. What that was remains a mystery. But it soon passed into history because the battalion was ordered to move back into the line the next day. At 1345 on 14 Jun, they filed out and boarded buses for Pont Noyelles where they arrived at 1530. They had a hot dinner there then they slogged up to their new positions at 2145. They passed through Bonnay and across the River Ancre then up the ridge to the Brickworks. The guides who were supposed to meet them did not show up so the CO decided to go forward to find the way himself. Eventually, they found the HQ of the 26th Battalion and were guided into their positions in the reserve lines behind the 32nd and 30th Battalions in the front lines. The changeover was eventually completed without casualties by 0200 the next morning. The Bray – Corbie road lay in the centre of their lines which occupied a position about seven kilometers north of Villers Bretonneux.

Things started very quietly with enemy artillery doing very little but influenza soon provided difficulties and men started to go sick with it almost straightaway. Some were bad enough to need evacuating. On 17 Jun, 17 men were removed to hospital with the illness. Similar numbers were evacuated each day. The fine weather held though and for men who had endured the snow, mud and rain of the European winter, this was a blessing indeed. It was not until 23 Jun that the influenza epidemic eased. On 26 Jun, the battalion was relieved by the 56th Battalion and by midnight, the 31st had left the line and trekked back without casualties. They occupied positions around the La Houssoye Switch but they were still exposed to German artillery and so normal training could not be conducted. Initially, the men were able to rest but some training was carried out on the Lewis Gun. As the battalion establishment for that weapon was now 36, rather a far cry from the initial two which certain military authorities thought was still too much for an overrated weapon, having all the men trained in its use was an obvious benefit. One of the difficulties which this new found abundance lead to was not immediately obvious; Someone had to carry a lot more ammunition for these extra guns. The average loads for the forward troops went up considerable as did the effort needed to keep up the ammunition supply.

As well as this training, the battalion supplied large numbers of men for general working parties in the area, especially ones for burying cables. Thus June 1918 ended. There had been fewer casualties for the month though, one man killed, another died of his wounds while a further nine were wounded badly enough to require evacuation to hospital. Only 15 reinforcements had arrived and so the battalion had a strength of 21 officers and 508 ORs with the battalion but another 23 officers and 406 ORs were on other duties, with the nucleus, at training courses of in hospital.

July found them still resting, notionally, near La Houssoye Switch but actually working hard on labouring jobs in the surrounding area. They laid cable near St Gratien, provided carrying parties and even built a tennis court for the brigade HQ in Frechencourt. Work went on for the first week of July. On Sunday, 7 Jul, they found time for a cricket match after Church Parade. The next day, the weather broke and the long fine and warm days ended. Rain fell and the days were unsettled, windy and showery. On 12 Jul, a welcome load of comforts arrived for the men from the New South Wales Comforts Fund. It included cigarettes, tobacco, sweets, cards etc and was very much appreciated, especially the cigarettes which were hard to find in their area. On 17 Jul 1918, the battalion was again on its way back to the front. At 0915, they marched out, through Heilly and along the Heilly – Buire road and into the Dernancourt Sector. They relieved the 57th Battalion by 0100 the next morning without casualties in the trenches in front of Buire. The ground here was quite marshy and so the trenches were fairly shallow and were open to the observation of the enemy from the high ground behind his lines. Their positions were situated on both sides of the Ancre which made communications difficult sometimes.