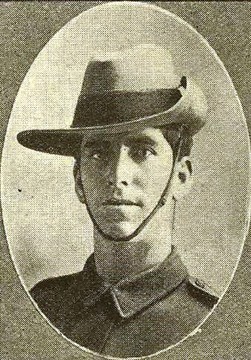

CONNELL, Leslie Peter

| Service Number: | 774 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | 14 September 1914 |

| Last Rank: | Private |

| Last Unit: | 9th Infantry Battalion |

| Born: | St. Lawrence, Queensland, Australia, 28 January 1893 |

| Home Town: | Brisbane, Brisbane, Queensland |

| Schooling: | Not yet discovered |

| Occupation: | Miner |

| Died: | Queensland, Australia, 23 July 1970, aged 77 years, cause of death not yet discovered |

| Cemetery: |

Mount Gravatt Cemetery & Crematorium, Brisbane PLOT - 4F 451 |

| Memorials: | Mount Morgan Gold Mining Company Honour Roll |

World War 1 Service

| 14 Sep 1914: | Enlisted AIF WW1, Private, 774, 9th Infantry Battalion | |

|---|---|---|

| 24 Sep 1914: | Involvement Private, 774, 9th Infantry Battalion, --- :embarkation_roll: roll_number: '9' embarkation_place: Brisbane embarkation_ship: HMAT Omrah embarkation_ship_number: A5 public_note: '' | |

| 24 Sep 1914: | Embarked Private, 774, 9th Infantry Battalion, HMAT Omrah, Brisbane |

Mountain Man Gallipoli Veteran

WORLD WAR ONE SERVICE

ENLISTMENT & TRAINING

At the time of Les’s enlistment, he was working as a miner at the Mt Morgan Gold Mine, and was a strapping 22 year + 8 months young man, 5’11” (180cm) tall, with a dark complexion, blue eyes, brown hair, and weighed 12 stone (76kg).

The date recorded on Les’ AIF enlistment document is 14th September 1914, however his service actually dates from 20th August 1914, when he enlisted in the Army Engineers Corps in Mt. Morgan, and was formally sworn-in the next day – 21/8/14.

Les was one of just six Mt Morgan miners selected to join the Army Engineer Corps, and common sense dictates that these six men must have been considered experienced above average skilled miners to have been selected.

Apparently, men who had worked at the Mount Morgan Mine, enjoyed referring to themselves, and be called by others, “Mountain Men”

The following are notations from Les’s personal diary, that he started when he first enlisted, and which has been invaluable, together with other odd bits and pieces that Les hung onto, in the putting together of this story.

22nd August - Send off at Grand Hotel 22nd August 1914, Going to War.

23rd August - Photos taken. Mt Morgan public send-off.

24th August - Left Mt Morgan en-route for Enoggera

Author’s Note

Indications are that Les travelled from Mt Morgan by train to Mackay, and then by the steamship SS Bombala to Brisbane, and hence onto Enoggera. There was an undated and unattributed small newspaper article, which after Les’s death in 1970, was found amongst his possessions.

This article was presumably cut from a local Mt Morgan publication, which appeared shortly after Les and three others left for Brisbane. Note that the article refers to Private Connell, thus supporting that Les had indeed enlisted on 20th August into the Engineers at Mt Morgan. The article reads:

Private Leslie P. Connell was residing in St Elmo Boarding House, and went away with Tom Shepard and J. Beckett, also of St Elmo. Another boarder of Mr. Thiel’s, Sid Broom, left for Brisbane on Tuesday to enlist.

Clearly Les and the other two from St Elmo’s were pals, because they stayed so close to each other that they all ended up going to the 9th Infantry Battalion, with their army service numbers being sequential.

• John Raymond Beckett, Serial Number - 773

• Leslie Peter Connell, Serial Number - 774

• Thomas John Shepard, Serial Number - 775

For reasons unknown, Sidney Broom ended up in the 31st Infantry Battalion.

Of the four chaps who left Mt Morgan on the same day to “go to war”, Les was the only one to survive.

• 773 Pte John Raymond Beckett (9th Bn) - Killed-in-Action 31st Oct. 1917

• 775 Pte Thomas John Shepard (9th Bn) - Killed-in-Action 20th Sep. 1917

• 1522 Pte Sidney Broom (31st Bn) - Killed-in-Action 19th Jul. 1916

Back to Les’s diary entries………………….

LPC Diary - 25th August, 1914 Arrived Brisbane. Had a few Hours. Arrived Enoggera Camp 4pm. Transferred from Engineers to Foot Infantry. Cup of tea in camp - nothing to eat.

Author’s Note

Apparently for the remainder of August and the bulk of September, Les was kept too busy to make entries into his diary for there are no further entries until Les wrote the following , which appears to have been made on or around 24th-25th September, 1914.

LPC Diary: At Enoggera. Had plenty of drill. Had to be vaccinated and twice inoculated. Also had seven teeth drawn and two stopped. Got influenza and sore throat. Had a week’s spell. Left Enoggera 3 o’clock Sept. 24th to go on-board troop ship “Omrah”. Left Pinkenba 12 noon 24th. Fair crowd on wharf. Have had a good voyage so far, have not been sick

For the reader to gain an understanding of the training the 9th Bn men went through at Enoggera, below are extracts from the book “FROM ANZAC TO THE HINDENBURG LINE – The History of the 9th Battalion A.I.F.” by the 9th Battalion AIF Association.

This book was published in 1936 and written by WW veterans of the 9th Bn when their memories would still have been relatively fresh. The book is well worth the read as it is very detailed, and greatly expands upon a number of incidents at Gallipoli in which Les was involved, but about which only abbreviated mention is made in his personal diary.

“During the third week of August 1914 a few military officers in uniform and a number of men in ordinary civilian attire could be seen pitching tents in Bell’s Paddock, Enoggera, a pretty spot on the outskirts of Brisbane.”

On August 22nd a contingent of 123 men from North Queensland left Townsville by the S.S. Bombala….ten more men joined the ship at Mackay, and they reached Brisbane on the 25th.”

For the first week or two little drill was done, the troops being engaged mainly in preparing the camp site, unloading stores, pitching tents, building cook houses, and in other necessary work.”

At first many men had to go on parade in their civilian clothing; suits of dungarees, and white cloth caps were issued to them as soon as possible, and uniforms and equipment given out when they came to hand.”

“By August 28th, three weeks and a half after the declaration of war, 52 officers and 1237 other ranks were in the camp at Enoggera. This number had by September 3rd, increased to 65 officers and 1784 other ranks”

Author’s Note

Not all these men were posted to the 9th, as a unit of the Light Horse were also being assembled at Enoggera.

9th Bn Book: “As the camp settled down, squad and company drill was begun, and then battalion drill. Rapid progress was made in both numbers and in training, and on September 12th it was announced that the Queensland quota for the Expeditionary Force was complete.

Leave was given very sparingly, but on Sunday afternoons the camp was thrown open to visitors and relatives, and friends of the troops formed many a merry little picnic party, some of these lasting till 10pm.”.

“On Saturday September 19th, the troops who were to leave for overseas marched from Enoggera to the city, in full marching order, and, after traversing the main streets with fixed bayonets, to an accompaniment of tremendous cheering, they returned to camp apparently as fresh as when they had started, which was very credible to men with just a month’s training.”

EMBARKATION & VOYAGE

9th Bn Book: “On September 22nd “H” Company, with the battalion band and drummers at its head, marched to the railway station, about a mile from the camp, and entrained for the short trip to Pinkenba, at the mouth of the Brisbane River, where it boarded the 8,130 ton Orient liner, Omrah (then known as ‘A5’). Its task was to prepare the ship for the embarkation of the rest of the battalion. The remainder of the 9th left camp at 4:15am September 24th, and were on board by 8 o’clock.”

Author’s Note

It seems incredible that the men of the 9th battalion received only two-three weeks training before being deployed overseas, although additional training was conducted during the voyage and while the battalion was in Egypt. In present times, the minimum training before Australian Infantry troops would be considered ready for overseas deployment, is at least 9 months.

Apart from the incident involving the Australian light cruiser HMAS SYDNEY (which was escorting the convoy) and the German ship SMS EMDEN, which will be mentioned in more detail below, the remainder of the diary and book entries about the voyage are mostly unremarkable, and deals with the various ports of call, on-board training, routine duties and sports events conducted on the Omrah.

9th Bn Book: 8th November 1914 - “Shortly before dawn next morning the convoy was passing fifty miles to the east of the Cocos Islands. About 7am the SYDNEY was seen to swing round and to steam away westward at full speed………Some of the men on the Omrah heard a faint sound like the beating of a big drum, but did not pay any particular attention to it………Then at 11.10am a wireless message was received from SYDNEY: EMDEN beached and done for……The news was announced to the troops on the Omrah at 11:10am during a Beer-Parade, there was great rejoicing on-board, and the victory was celebrated by the issue of an extra ration of beer.”

Author’s Note

The SMS Emden was an Imperial German navy light cruiser. Shortly after the outbreak of WW1 (4th August 1914) the Emden began independent raiding actions in the Indian Ocean. The EMDEN spent nearly two months operating in the region, during which time the EMDEN captured nearly two dozen ships, sank the Russian cruiser ZHEMCHU and the French destroyer MOUSQUET.

On 9th November the EMDEN sailed to attack British facilities on the Cocos Islands. Seeing the EMDEN approach a Cocos Island wireless operator sent out an SOS, that was heard by HMAS SYDNEY. The SYDNEY immediately steamed towards the Cocos Island, engaged and caused serious damage to the EMDEN, forcing its Captain to run the EMDEN aground. Out of the EMDEN’s crew of 376, 133 were killed, and most of the survivors were taken prisoner. The German party, that had been landed to destroy the Cocos Island wireless station managed to commandeer an old schooner and eventually returned to Germany.

9th Bn Book: “Thirteen of the transports, including the ‘A5’ went ahead to coal an water at COLOMBO, which was reached at midday on the 15th. Next day there were transferred to the ‘A5’ 44 of the survivors from the EMDEN, for whom the 9th battalion had to provide a guard of 60. Commanded by Captain Melbourne, the guard was drawn up on the deck in two ranks to receive the prisoners – the Chief Engineer, the Torpedo Lieutenant, two petty officers, and 40 seamen……The prisoners boasted that none of those on the ship would ever reach ADEN or ENGLAND alive. They exchanged with members of the 9th a number of Mexican dollars brought from the EMDEN: some of those showed signs of fire which had broken out in the ship”

LPC Diary: 16th November - “…..during the day 40 of EMDEN’s came aboard, we making no show they were put for’ard, the officers being given cabins.

Author’s Note

Following Emden’s stranding, later in 1914 salvage operations were commenced. Numerous items of her equipage and structure were salved and taken to Australia and Great Britain as War Trophies.

During these salvage operations, 6,429 Mexican silver coins were recovered from two safes aboard Emden. There were, in addition, a number of US $20 gold coins recovered.

The vast majority of these silver coins were Mexican 8 Reale pieces, sometimes referred to as Dollars. The obverse of the coin bore the Mexican National emblem of a spread-wing eagle with a snake in its beak surrounded by a wreath, with ‘REPUBLICA MEXICANA’ at top.

These Mexican coins were the most popular international trade currency of the time throughout the East Indies and along the China Coast. Emden’s hoard was possibly taken as plunder and was probably also utilised to pay local levies and as wages for the ship’s company whilst in Asian waters.

Of the 6,429 salvaged silver coins from the Emden hoard, 1,000 were mounted as commemorative medallions in 1918 by the Sydney jeweller and silversmith, W. Kerr.

These mounted pieces were intended to be presented to all officers and ratings aboard Sydney at the time of the Cocos battle, or to the next of kin. Some were also presented to the staff on Cocos Island as well as to the Admiralty, Australian War Memorial and other ‘approved’ institutions. Some were also sold off to the public.

EGYPT & MORE TRAINING

Author’s Note

On December 4th the OMRAH reached Alexandria in EGYPT, and over 6th & 7th December, the 9th battalion men disembarked and headed for MENA Camp, outside of Cairo. To say that to start with, the camp was basic, is an understatement, as demonstrated by the following.

LPC Diary: 7th December - Left ALEXANDRIA for MENA via CAIRO. Arrived CAIRO 5pm. Reached camp 9pm. No tents – all sand.

9th Bn Book: The last stage of the journey to MENA Camp was made in open electric tram-cars. Some parties on their arrival were formed up into lines of companies in the dark and issued with two blankets each, and they slept in the open on the sand. Other parties were met by a guide who, after leading them over the desert for about half-an-hour, stopped, pointed to some more sand, and said: ‘There’s your camp’. As they settled down for the night, they were thrilled to see the Pyramids showing up clearly in the glorious light, and apparently quite close.”

Author’s Note

The next day it began raining, which carried on at intervals, for two days. After being at MENA for some days, tents began arriving and by 14th December there were tents for all. Eventually mess huts were also built, so that the men could eat in comfort.

The 9th, 10th & 11th battalions then settled into a steady routine of training, fatigue or guard duty.

During the their approximately 11 weeks at Mena, the men received extensive training in company & battalion manoeuvres & skirmishing, Brigade attacks, trench digging/defence, shooting etc.

The training was hard and intense, but it served to toughen the men for what lay ahead.

It was not all work however, as the men were often granted short leave passes to go into CAIRO for a day or at night, or to experience the local sights such as the Pyramids, Sphinx, donkey & camel rides.

Despite the leave passes, as demonstrated by the following, the men were not sorry to leave MENA.

LPC Diary: 28th February 1915 - Left MENA at 5pm after 11 weeks work on the sand. Everybody pleased. 10th, 11th, 12th also leave tonight. Entrained at CAIRO at 5pm.”

9th Bn Book: “On the 27th February the 3rd Brigade was detailed to move from EGYPT to the island of LEMNOS, in the AGEAN SEA – the battalions were unaware of their destination at the time – and that night, the Brigade’s last at MENA, was marked by constant outbursts of cheering, which would spread through the battalion, and be taken up by unit after unit till the sound was lost in the distance in the artillery lines.”

LEMNOS & EVEN MORE TRAINING

Author’s Note

After leaving MENA Camp 9th battalion travelled by train from CAIRO to ALEXANDRIA, where together with the 10th battalion, they boarded the S.S. IONIAN for a relatively short, but extremely uncomfortable voyage to LEMNOS.

LPC Diary: 1st March 1915 - Arrived ALEXANDRIA 11am and went aboard ‘IONIAN’ which is very dirty and room very close to stables.

LPC Diary: 4th March 1915 - Everybody waiting to get ashore. Boat very dirty.

9th Bn Book: “The 10th battalion was also detailed to the ship, in which the troops were packed like sardine: at night it was difficult for those retiring late to find a place to lie. One section commander wrote: ‘My section, 15 men, allotted between decks 6ft x 12ft (sic: 2 metres x 4 metres), could not stand upright.’

The ship belonged to the ALLAN LINE. Which was sardonically referred to as the ‘Hungry Allan Line’ by many of those on board.

The IONIAN was called by the troops ‘One-Onion’ but her smell was much stronger than that of the onion, as she had carried horses on her previous voyage, and had afterwards not been properly cleaned. ……..At one point the butter was very rancid. One of the 9th’s officers, when talking to the Scotch master of the ship asked him how long the IONIAN had been carrying troops, and was proudly informed that the ship had taken troops to and from SOUTH AFRICA fifteen years before, ‘My word, skipper’ said the Australian ‘you must have taken on a hell of a supply of butter at the time’, and he decamped before that worthy could grasp his meaning.

A remark often passed about this ship was ‘Iron boat, iron decks, iron rations, and iron men’. The men had to sleep on the hard iron decks, and during the voyage to live on so-called ‘iron rations’ – hard biscuits and tinned corned beef.

The vessel was not fitted with any mess tables, there was no more than one light for each troop-deck, very little ventilation, and the only means of access to or from the troop-deck was a narrow upright iron ladder”

Author’s Note

Records show that for the first month the 9th battalion were on the Island, much of this time was spent performing manual labour duties, such as unloading ships, quarrying stone to build jetties, building wharfs, building roads, and re-floating supply barges that had been blown ashore during gales, etc.

Also, during this time, increasing numbers of warships, and troop transport ships (with troops) came and anchored in MOUDROS Harbour, in the build-up to the GALLIPOLI Campaign.

Often a warship would return from the DARDENEL STRAIGHTS with battle damage, after having been shelled by Turkish shore batteries, which the ships were attempting to destroy.

For much of the time the weather was poor, with very high winds, rain or a combination of both.

One incident that went to break the monotony during this period, occurred when the 9th battalion received a request to assist a torpedo-boat crew, whose boat had been driven onto rocks by gale-force winds. Below is a description of the incident:

LPC Diary: 21st March 1915 - Wind still blowing. Was again orderly. Tobacco very scarce. Just go in bed when they called for volunteers to go and assist a wrecked torpedo-boat on the other side of the island. Rain and wind blowing terrific. Very cold. Got there about midnight and found them all safe. Started back and the guide lost us. Started off on our own and arrived home at 5:15am. The rest of the party getting home at 7:15am.”

9th Bn Book: “On March 21st, a party of about 150 strong, under Captain Milne. Went across the island to assist in the rescue of a crew of a British torpedo-boat, the ‘063’, en-route from Port Said, which had been wrecked during the gale, which had begun on March 19th. When the party arrived, after a difficult and uncomfortable march, with sleet driving in their faces, it found that the crew had all reached the shore. Later, however, some of the men decided that the day had not been wasted, as they discovered a couple of kegs of rum which had been washed ashore: unfortunately for them, an officer arrived on the scene and ordered the rum to be poured out and let run to waste. A quantity of navy chocolate, in good thick slabs, was also discovered, and greatly appreciated by the party.”

Author’s Note

The 9th battalion book, contains the following explanation of why the 9th Bn men (and others) spent such a long time on the island.

9th Bn Book: “About this time (sic: early April) the first official intimation was received by 3rd Brigade HQ that the brigade was to land at the Dardanelles, and would be the covering force (sic; be first to be landed, to provide covering fire for subsequent troop landings) for the operation.

M. Venizelos, the Greek Prime Minister, was enthusiastically in favour of the Allies, and especially wished Greece to gain possession of CONSTANTINOPLE. During their early days at LEMNOS it had been announced to the officers of the 9th that a force of 40,000 Greeks was to assist in the landing at the DARDANELLES. However, a political crisis occurred, in which the Venizelos Government fell; it was then discovered that the other Allies had promised CONSTANTINOPLE to Russia as one of the spoils of war. Greece thereupon then became a neutral nation and the proposed Greek force was cancelled.”

Author’s Note

At the beginning of April 1915, the 9th battalion recommenced training in earnest, by conducting battalion attack manoeuvrers, then on 8th April the battalion struck camp, and boarded the British India Company Liner MALDA.

While on the MALDA, and still in MUDOS Harbour, the 9th conducted ship disembarkation drills, combined with land attack manoeuvres. Following is a description of this training:

9th Bn Book: “At this time disembarkation practice began, at first in the daytime and later at night. This was very strenuous work, as after landing, the troops had to charge up one hill and then another until they were exhausted. However, these exercises made all ranks quite fit for the work ahead of them.”

Author’s Note

While on the MALDA men were issued for the first time with their battalion specific shoulder colour patches.

Prior to this, battalions had been distinguished from other units by a brass numeral on the shoulder strap, which were taken away when the colour patches were issued.

In the infantry, the brigade was denoted by the lower colour, and the battalion by the upper.

These colour patches soon came to have great sentimental value to Australian troops, as it symbolized their unit.

There we no Regiments in the AIF infantry, and the ‘digger’ came to have the same affection for his colour patch, as the ‘Tommy’ had for his metal badge.

As an aside, given that Les’s occupation before enlistment was a ‘Miner’ he soon became a ‘digger’ in every sense of the word.

It was also while on the MALDA, that Les received advice that he had been appointed a Company Scout. Here are the relevant entries in Les’s diary, and mentioned in the 9th Bn Book, a most prophetic message that was read-out to the troops.:

LPC Diary: 12th to 15th April 1915 - Have been appointed Company Scout, and have to land with ‘B’ Company.

LPC Diary: 20th April 1915 - Had lecture of Lieutenant in charge of scouts in regards to landing place.

9th Bn Book: “On April 21st a letter from the Brigadier was read to all ranks, urging them to do their best in carrying out “a most difficult operation, landing on an enemy’s coast in the face of opposition. It ended with the words: ‘You now have a chance of making history for Australia’.”

Author’s Note

For the purpose of the landing, scouts were assigned to fight their way as far inland as possible before the Turks could counter-attack, this therefore means that Les was right at the ‘pointy end’ of the assault up the cliffs at Gallipoli. At 11am on 24th April, Les together with the men of 9th battalion ‘A’ + ‘B’ Companies, who were to be in the very first-wave of boats to land at Anzac Cove (Gallipoli) were transferred from the MALDA, to the battleship HMS QUEEN, in preparation for the landing, the next day.

GALLIPOLI LANDING

The Ottoman Turkish Empire entered WW1 on the side of the Central Power (German & her allies) on 31 October 1914. The stalemate of trench warfare on the Western Front convinced the British Imperial War Cabinet that an attack on the Central Powers elsewhere, particularly Turkey, could be the best way of winning the war.

From February 1915 this took the form of naval operations aimed at forcing a passage through the Dardanelles, but after several setbacks it was decided that a land campaign was also necessary.

To that end, the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force was formed under the command of General Ian Hamilton. Three amphibious landings (English, French & Anzac Forces) were planned to secure the Gallipoli Peninsular, which would allow the navy to attack the Turkish capital Constantinople, in the hope it would convince the Turks to ask for an armistice.

The 25th April 1915 at Gaba Tepe (later known as Anzac Cove), was the part of the amphibious invasion assigned to the Anzac (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) Forces, the total ANZAC strength was 30,638 men.

At 01:00 on 25 April the British ships stopped at sea, and thirty-six rowing boats towed by twelve steamer launches embarked the first six companies, two each from the 9th, 10th and 11th Battalions. Les has been assigned as a Scout with the 9th battalions’ first-wave ‘B’ company, and so, he would have been one of these thirty-six rowing boats.

First wave landings. The dotted lines from the red ships indicate the first six companies of the first wave. Those from the orange ships are the second six companies. The solid red lines show the routes taken once ashore.

With 90 yards (88m) to go, the steamers cast-off the rowing boats, which then used their oars to get to the shore.

The Anzacs had inadvertently landed one mile (1.6 km) further north than intended, and instead of an open beach they were faced with steep cliffs and ridges up to around three hundred feet (91 m) in height.

However, the mistake had put them ashore at a relatively undefended area. At Gaba Tepe further south, where they had planned to land, there was a strong-point, with an artillery battery close by equipped with two 15 cm and two 12 cm guns, and the 5th Company, 27th Infantry Regiment was positioned to counter-attack any landing at that more southern point.

On their way in, the rowing boats had become mixed up. The 11th Battalion grounded to the north of Ari Burnu point, while the 9th Battalion hit the point just south of it, together with most of the 10th Battalion.

The question of who was first ashore became a contentious issue soon after the landing.

The Sydney Mail newspaper proposed Lance Sergeant Joseph Stratford, a New South Wales man who had enlisted in Queensland's 9th Battalion and died on the first day, was the first to step ashore.

However, Lieutenant Duncan Chapman, another 9th Battalion man, claimed priority in a letter dated 24 June 1915: “My boat was the first to land and, being in the bow, I was the first man to leap ashore.”

In a letter to a newspaper in 1934, 364 Private James Roy Speirs of A Company 9th Battalion states he was in the boat and saw Duncan hop out first.

The official Australian WW1 historian Charles Bean, supported Chapman and mentioned Frank Kemp, a sergeant scout, who also corroborated the story.

Because Les was attached to ‘B’ company, it is unlikely he would have been in the same boat as Lt. Duncan Chapman, which appears to have been predominantly carrying ‘A’ company men.

Although he may not have been in the very first boat to touch shore, as Les had been appointed as a Scout, it stands to reason he would have been in one of the boats intended to land before most of the others. Thus, it is probable Les was in one of the very first couple of boats to make land on that historic day.

The hills surrounding the cove where the ANZAC’s landed made the beach initially safe from direct Turkish artillery fire.

Fifteen minutes after the landing, the Royal Navy began firing at targets in the hills.

The plan was for them to cross the open ground and assault the first ridge line, but they were faced with a hill that came down almost to the water line. There was confusion while the officers tried to work out their location, while under small arms fire from the Turkish infantry, who had a platoon of between eighty and ninety men at Anzac Cove and a second platoon in the north around the Fisherman's Hut.

A third Turkish platoon was in a reserve position on the second ridge. They also manned the Gaba Tepe strong-point, equipped with two obsolete multi-barreled Nordenfelt machine-guns, and several smaller posts in the south.

Men from the 9th and 10th Battalions started up the Ari Burnu slope, grabbing the gorse branches or digging their bayonets into the soil to provide leverage.

At the peak they found an abandoned trench, the Turks having withdrawn inland. Soon the Australians reached Plugge's Plateau, the edge of which was defended by a trench, but the Turks had withdrawn to the next summit two hundred yards (180 m) inland, from where they fired at the Australians coming onto the plateau.

As they arrived, Major Edmund Brockman of the 11th Battalion started sorting out the mess, sending the 9th Battalion's men to the right flank, the 11th Battalion's to the left, and keeping the 10th Battalion in the centre.

The entry in Les’s personal diary for that day, reads:

LPC Diary: 12th - “Landed at Gallipoli at 4:30am. Had eleven hours fighting and was wounded in the arm. Went aboard ‘Gascon’ and was taken to Cairo, where we land on the 28th. Went to Heliopolis to Mena, by the 30th.”

Les’s note that he had 11 hours fighting, puts him being wounded at around 3.30 in the afternoon.

The position of Anzac front-line at that time was “Baby 700”.

Baby 700 is a hill between Russell's Top and Battleship Hill, on the third ridge from the Aegean coast.

It was named after its supposed height above sea level, but its actual height was only 590 feet (180 m).

Author’s Note

This is an account of an action in which, possibly/probably, Les received his wound:

……………..At 15:15 Captain Joseph Peter Lalor (grandson of the Eureka Stockade Peter Lalor) left the defence of The Nek to a platoon that had arrived as reinforcements, and moved his company to Baby 700. There he joined a group from the 2nd Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Leslie Morshead. Lalor was killed soon afterwards.

The left flank of Baby 700 was now held by sixty men, the remnants of several units, commanded by a corporal. They had survived five charges by the Turks between 07:30 and 15:00; after the last charge the Australians were ordered to withdraw through The Nek.

As mentioned in Les’s diary, supported by his official service record, after being wounded (gunshot wound to right arm/shoulder, involving a fracture of the Humerus bone) he was evacuated from Anzac Cove, to the hospital ship, HMHS Gascon.

Author’s Note

One of the most interesting ‘souvenirs’ that Les brought home from the war is a MEDTAG, meaning a tag that is placed on a wounded soldier when first treated by stretcher bearers, identifying the wounded soldier, and giving a brief description of their wound and the treatment so far given.

Beside identifying Les with his name, rank, service number and unit, the tag also states that his wound was a “Broken Right Humerus”……..Les’s official medical record states the injury was due to a GSW – a gunshot wound. It is not possible to read on the tag, what treatment was initially provided.

The tag is attached to the soldier by a length of string (usually around the neck) and stays with them until they get admitted to a hospital, where the tag is no longer needed, and thus removed.

It is likely that this tag was removed from Les soon after boarding the Gascon Hospital ship.

Upon arrival in Cairo Les was admitted to the 1st Australian General Hospital (1AGH), at Heliopolis.

At the 1AGH Les underwent surgery on his wound, and three days later, was sent to the Mena Camp for a spell of recovery. This is Les’s diary entries for that period:

LPC Diary: 2nd May - Went under ether to get bullet taken out, but was false alarm. (Author’s

Note: Medical records show that a bullet was there, but could not be removed, and as it was causing Les ‘no pain or inconvenience’, Doctors decided leave it there). Got splints off after four weeks. Had a week in hospital after, and a week at base details.

RETURN TO GALLIPOLI

Following Les’s full recovery at Mena Camp, on 7th June he began his journey back to Gallipoli. This is his diary entries regarding his return to the 9th battalion:

LPC Diary entries……….Left for the front on June 7th. Was in the cook house on the ‘Saign Chrow’. Was transferred to the ‘Osmanick’ on the 16th. Got to Gallipoli and did not land. But anchored at Inbros after daylight.

LPC Diary: 17th June 1915 - Landed at daylight and found things very quiet. Went and joined our battalion. Had a few shells over our ‘posy’.

Author’s Note

On the 16th November, the 9th Battalion left Gallipoli for a period of ‘rest & recuperation’ on the Island of Lemnos. The men of the 9th did not know this at the time, but 16/11 was the last time they would set foot on Gallipoli, because before they could return, all allied forces were evacuated from the Gallipoli Peninsular, in an operation that took place between 15th and 20th December 1915.

As Les re-joined the 9th battalion on 17th of June, this means he had five months at Anzac before the battalion’s relocation to Lemnos.

During this five month period, Les was involved in several actions & was shelled & machine gunned multiple times. Also during this period, he experienced all the hardships that were characteristic of the Gallipoli campaign……Heat, Flies, Disease, Water Shortage, Poor Diet…..the list goes on.

Unfortunately Les’s diary entries stop after 28th August. Presumably because this entry (28th) was made on the last available page of Les’s diary, and at Gallipoli, he was unable to purchase a fresh diary book.

Highlight entries from Les’s diary and the Battalion Book, for that period, are:

LPC Diary: 28th June 1915 - Was given order to have dinner over and be prepared to move by 12:15pm. Moved from our ‘poseys’ up to where the 12th were entrenched and out through a sap in front of firing line. Advanced up hill and was waiting there when a shell exploded in front of me, covering me and some mates in dirt. Found that no-one was hit so started to retreat when another shell exploded alongside of me, too close for my liking. Returned behind the hill and went up again. A chap near me got hit in the leg, so carried him back. A good few casualties in our company, also ‘B’ company, the only ones out. 4 wounded and 1 killed in our section.

9th Bn Book: “At 8:30am on June 28th General Birdwood received a message suggesting that he should make a minor attack at Anzac to prevent the Turks from sending reinforcements to Helles, where the VIII British Corps was attacking at 11:30am on that day. It was decided that the operation should be carried out on the right flank by the 2nd Light Horse Brigade and the 3rd Infantry Brigade. Orders for the attack were drawn-up and sent at 10:30am to the two Brigadiers concerned, and consequentially the local arrangement had to be made very hurriedly.

In the 3rd Brigade, at 1pm two companies of the 9th were to go out from Holly Ridge and Silt Spur towards Sniper’s Ridge and its continuation, the Knife Edge, and two of the 11th were toile out on Silt Spur and Turkey Knoll to cover them. At the same time the Light Horse were to advance to the right. ‘B’ + ‘C’ companies, under Major R. H. Walsh and Captain Young respectively, were chosen for the 9th battalions’ task, both being fully up to strength. At 1:15pm they left their trenches at point a quarter of a mile apart. The southern company (‘C’) on its way to the starting point had to pass round the shoulder of a hill under enemy observation from Gabe Tepe. This was equivalent to sending the Turks a message that an attack was about to be made, and as soon as the men reached Oratunga Sap, a communications trench leading to the front line, shrapnel and machinegun fire fell on them, and continued all the time they were in the sap…….Although the attack on the Knife’s Edge failed, that against Sniper Ridge met with some success……the object of the whole movement – the holding down of the enemy’s local reserve to this area – had been attained.

The two companies lost 37 killed and 62 wounded…….This operation was, with the exception of the Landing, the most trying the battalion had yet experienced”

LPC Diary: 29th June 1915 - Terrible hot touch of influenza, and a bit weak after yesterday.

LPC Diary: 17th July 1915 - Been sick all day, like influenza.

9th Bn Book: “Sickness among the troop was now putting in an appearance, and, as it increased, it became one of the great difficulties with which the men had to contend until they left the Peninsular”. -ooOoo-

LPC Diary: 6th August 1915 - ‘Abdul’ opened fire at daylight this morning and took trench we captured a few nights ago. One chap in our trench got wounded in neck. The trench was recaptured by us again. Got orders to pack up. 1st and 2nd Brigades going to attack today. A lot of shrapnel came over today. After bombing at 5:30pm 1st Battalion attacked and were successful in getting three lines of trenches. Our Battalion firing on position in front. 2nd Brigade also successful in their attack. Tommies landed at Salt Lake and were also successful.

9th Bn Book: “…….a large scale attack was to be delivered against Turkish defences at Lone Pine in the afternoon of August 6th, a few hours before the main operation began (e.g.: British landing at Suvla Bay) and this, it was hoped, would pin down the local reserves which otherwise would be sent to Hill 971 and Suvla. The role of the 9th Battalion was to open heavy rifle fire on the opposing trenches while Lone Pine was being assaulted by the 1st Infantry Brigade. This attack, supported by a bombardment from warships and field guns, occurred at 5:30pm. After supporting the charge, the men of the 9th, as also the Turks opposite them, sat on the parapet and watched the attack. They could do nothing to help, on account of the danger of hitting their own comrades.”

LPC Diary: 11th August 1915 - Had a close shave today part of a shell missing me by inches.

LPC Diary: 14th August 1915 - Was on duty till 3pm when I had to be relieved as I felt very crook like Dengue. Saw Doctor who put me off duty.

LPC Diary: 15th August 1915 - Had restless night. Still have aches. Had nothing to eat for 2 days.

9th Bn Book: “Aug. 14. Considerable sickness in battalion.

LPC Diary: 16th August 1915 - Feel a bit better today but cannot eat yet. A good few shells burst close today, one sending pieces of dirt into my posy which gave me a bit of a start. On cornflour which was very good. A good few leaving here sick.

9th Bn Book: “By the middle of August sickness had increased to such an extent that the 3rd Brigade could do little more than hold its line. In the three weeks following August 6th, 1,146 out of a total personnel of 3,622, that is, more than 30%, had been sent away from the Peninsular. The men evacuated were described by a Medical Officer as…………just skin and bone, arms and legs covered with septic sores; ill with dysentery; had to work in the trenches on bully-beef, bacon and biscuits.”

9th Bn Book: “Aug. 19. Rapid increase in Sick Parade during last fortnight”.

LPC Diary: 21st August 1915 - Had a good feed of bacon and eggs for breakfast.

LPC Diary: 28th August 1915 - Rifle fire heavy all night on left where I believe our boys had a success. Things a little quieter today. A few big six inch shells came over this PM one not exploding, landing a few yards away. Next one was better. It exploded and filled in a few ‘poseys’ and gave us a bit of a shock. Their planes came over for a look but did not do anything. Often a lot of boats outside, including as many as 8 Red Cross boats. When gunboats came, the torpedo boats kept guard outside.

- END OF LCP DIARY ENTRIES -

Author’s Note

From the beginning of September through to when the battalion left Gallipoli for Lemnos, the 9th was mainly engaged in static trench warfare with the Turk, and did not engage in any major attacks.

The main reason for this was the battalion was not in a fit state to conduct offensive operations, due to the high attrition rate of troops from illness. It was not only the men that were effected, and many of the battalion, and indeed 3rd brigade officers were stuck down, as demonstrated by the following excerpts from the 9th Battalion book.

RETURN TO LEMNO & EGYPT

On November 17th the 9th arrived back on Lemnos where, due cold weather, a shortage of blankets and appropriate clothing, the first few weeks were somewhat uncomfortable.

Shortly after arrival, due to an outbreak of Diphtheria, the whole of the 9th were placed in quarantine.

As a number of the men had lost their razors during the move from Gallipoli, and the battalion Medical Officer advised that beard growth might help protect the men’s throats during the cold spell, the Commanding Officer gave the order that all officers & men of the 9th were to cease shaving until further orders.

The result of this was that the battalion earned the nickname “The Hairy Ninth”, or “The Bearded Ninth”, which later became corrupted to “The Beery Ninth”.

A highlight of the 9th’s stay on Lemnos was recorded in the 9th battalion book, as:

9th Bn Book: December 25th - “Christmas ‘Billies’ were issued to all. These had been sent from Australia, where arrangements had been made by the various Soldiers’ Welfare Organizations that every man at the front should receive one. The billy-cans were filled with various ‘comforts’, usually chocolate, biscuits, and other food, or wearing apparel, such as socks and scarves.”

On December 26th again boarding a ship (the Grampian), and relocating to the Tel-el-Kebir camp, which is located in the Egyptian desert, 35 miles west of Suez, and 70 miles from Cairo.

Just like when the first arrived at Mena Camp and Lemnos, it was raining at Tel-el-Kebir when the 9th arrived on January 4th, and so the men once more had a soggy first night exposed to the elements, and commenced building the camp the next morning.

Shortly after the 9th arrived at Tel-el-Kebir, and presumably after they had finished building the camp, it was announced to the men that beside normal (battle) training, they would be undergoing what official battalion records state was “elementary work in ceremony”. What this meant, was being put through training in how to salute by numbers.

The men of the 9th felt humiliated that as battled hardened troops who had just completed a long and arduous stint a Gallipoli, that they were being required to re-train in basic drill that they had already been taught, when at Enoggera camp.

This training was thoroughly despised by all ranks, but it had to be done as the order had come from a higher-up authority.

One can only speculate that some incident might have occurred wherein some British “brass” felt that they had not have received the proper respect to which they believed they were entitled, and thus the order came down in an attempt to bring the free-spirited diggers back in line?

On January 25th 1916, the battalion left Tel-el-Karbit and were transported by train to Serapeum, on the west bank of the Suez Canal, approx. 8 miles south of Ismailia, arriving at about 11pm.

The next morning the battalion crossed the Suez Canal by ferry, and marched through the desert to a camp about a mile east of the canal.

On the 27th, ‘A’ + ‘B’ companies were marched 9 miles through soft sand to set-up a defensive position at a place called Gebel Habeita, and next day were joined by the rest of the battalion.

The purpose of the 9th being moved to this position was to defend the strategically important canal against potential attack by the Turks, which the Turks had earlier attempted to capture in early 1915.

Their time defending the Suez Canal was a terrible time of hardship for the men of the 9th. To defend against Turkish attack, the men needed to dig trenches, but the soft sand simply kept collapsing and filling in what had just been dug-out. Sandbags were used to line the walls of trenches, but time and again, strong winds would blow enormous amounts of sand into the trenches, which then had to be once more dug-out.

At first the food and water was bad, with an initial allocation of just one half a gallon (2.25 litres) of water per man, per day. After a week however, the rations and water improved.

On February 5th the Brigadier visited the 9th, and afterwards gave instruction that the men were to receive half an hour of “ceremonial drill” training each day. A few days later, there was an outbreak of mumps in the 9th, resulting in a number of the men having to be hospitalized.

Some thought it was divine retribution for the Brigadiers orders for the saluting drill!

In the part of the 9th Battalion Book that mentions the mumps incident, is the following interesting description of how the sick men were transported to hospital: -

”…..the sick men were evacuated to hospital, some in ‘cacolets’ (a kind of skeleton invalid-chair) on camels, and some on light sand-carts, which had very-broad tyre wheels."

Les’s medical records show that on 20th February 1916, he was admitted to the 1st Australian Casualty Clearing Station (CCS) at Serapeum, only returning to the battalion of 26th February.

Records do not state the reason why Les was admitted to the CCS, but given the timing, it was likely due to mumps.

On February 15th a highly significant event happened…….advice was received that the A.I.F had decided to create two new divisions. As there were only two ‘spare’ brigades, Birdwood ordered that the original 16 battalions be split in half, to create 32 battalions, which would then be brought-up to full strength with reinforcements. The ‘daughter’ battalion of the 9th, would be the 49th.

On February 26th lots were drawn-up and with great sadness, half the officers and men of the 9th marched-out of the 9th to form the 49th battalion.

On 8th March 1916, after having been at Gebel Habeita for five weeks, the battalion was relieved by the light horse, and marched back to Serapeum.

The 9th was to spend just a little over two weeks at Serapeum, where it undertook further tactical training. The new Mk IV Lee-Enfield rifles were issued and Lewis Gun sections were formed. Lewis Gun Sections are discussed in detail later, in the next section that describes Fred Connell’s WW1 service.

At 6pm on March 26th 1916, the battalion left Serapeum and went via train to Alexandria. Together with the 10th battalion, they boarded the ‘Saxonia’ (a Cunard liner) and the following morning they were on their way to France.

As the rations on the ‘Saxonia’ were not considered particularly generous, the troops quickly nicknamed the ship, the ‘Starvonia’.

FRANCE & WOUNDED AGAIN

On April 2nd, the ‘Saxonia’ reached Marseilles and the 9th battalion disembarked at 5:45pm. The men were all issued with rations for 58 hours, and then marched to a train station, where they boarded a train, and began a most pleasant three-day journey through the scenic French countryside, heading north-west towards Belgium.

At 11am on April 5th, the train arrived at Godewaersvelde, near Ypres. After disembarking from the train, the battalion marched for approx. 5 miles, to where the men were billeted in farm houses & barns, around the villages of Strazeele, Merris, and Meteren.

From this location, the men could clearly hear the firing of artillery at the front.

The 9th battalion remained in this area for about a fortnight, during which time, they undertook further training, route-marches, were issued gas-helmets, and a scout section formed.

18th April 1916 – The battalion moved to Sailly-sur-la-Lys, which is approximately 5 miles west of Armentieres, and early next morning (19th April) moved to Rouge de Bout (two miles to the south-east of Sailly), relieving the 17th Lancashire Fusiliers.

‘A’ company was put into close-support of the firing-line at Ruedu Bois. The other companies were in support and reserve further back.

It was while in ‘C’’ company reserve area billet, that Les was wounded for the second time, on this occasion however, Les’s wounds were so serious and disabling, that after recovery he would be medically discharged from the AIF. Herein follows a description of that incident.

9th Bn Book: April 20th 1916 - “20th April, at approx. 1:15pm, ‘C’ company’s billets at Rouge de Bout were heavily bombarded by 5.9-inch howitzers, 50 or 60 high explosive shells bursting in their vicinity. Early in the bombardment a shell exploded in one of the huts, wounding four men, and others who ran to their assistance were caught by another shell. Later 47 casualties were caused by a shell which struck the wall of a large brick billet, behind which a considerable number of men were sheltering. At the time the Medical Officer (Captain A. McKillop) was inside the building attending to some of the earlier casualties. Lieutenant A. E. Fothergill, C.S.M G. T. Phipps, and 23 others were killed, and Captain McKillop and 47 others wounded. All the dead were buried the same evening. Chaplain Fahy (R.C.) and Lundie (Presbyterian) officiating.”

The Australian Official War Historian, Charles Bean, wrote the following account about this incident:

“The surroundings appeared perfectly peaceful, when shortly after midday on 20th April, the men of one company (‘C’ Company) billeted in a farm-house, a barn, a large loft, and three canvas huts in the adjoining field, were surprised by the burst of a shell in the road nearby. Other shells quickly followed, the fourth bursting in the entrance of a hut, and wounding several men. Others ran to help them, and the next shell burst amongst these. Lieutenant Fothergill was calling the men to shelter, and many were clustering beneath the wall of the house, when the wall was struck and brought down by another shell, killing or injuring nearly 50. The fire, which was that of a battery of 5.9 inch howitzers, continued for an hour and then ceased. Fothergill and 24 men had been killed, and the medical Officer (Captain McKillop) and 48 others wounded. Only once or twice afterwards during the war did the A.I.F. suffer, through shelling of billets, casualties approaching those of the 9th Battalion at Rouge de Bout”

Author’s Note

It is unknown at what stage of the bombardment that Les was wounded, however, it would be totally in keeping with his character that he was amongst the group that rushed to the aid of those who were wounded when the first shells exploded.

Ironically, Rouge de Bout translated to English means “The Red End”….it certainly was a red-end for many ‘C’ Company men that day.

A further irony is that just 3½ months later, Les’s older brother Fred was also severely injured by German heavy artillery, while he was in a reserve position area.

TREATMENT, RECOVERY & REPATRIATION

For Les to have been severely wounded while in a reserve area may well have been a blessing in disguise, for it undoubtedly meant that he would have received quicker transport and thus better medical treatment, than if he had received his grievous wounds in the front-line.

The reason for this being that rather than have the delay in having to be carried out of a battle zone on a stretcher, Les would have been quickly transported to doctors at a Casualty Clearing Station either by horse-drawn or motor ambulance using the undamaged rear area road networks.

Records show that Les had his wounds “dressed in the field” and then taken to the British Army’s 7th Casualty Clearing Station (which had doctors) at Merville, only about 5 kilometers from Rouge de Bout.

Given the nature of Les’s wounds, shrapnel in both arms & legs, the right-leg wound being of such severity it was later amputated, this may well have saved Les’s life.

The staff at the 7CCS moved quickly to send Les on to an even greater level of care, for the records show that later on the same day, he was admitted to the British Army 13th General Hospital at Bolouge, which is located on the French coast, 85 kilometres west of Merville.

On the 1st May 1916, Les’s family were officially advised that les was ‘Dangerously Ill’, as this was now 10 days after being hit by the shrapnel, and bearing in-mind that at the time of WW1 effective antibiotics had not yet been discovered, it seems a pretty safe bet that the seriousness of Les’s condition was due to the wounds having become infected.

Four days later, on 5th May, Les had his right leg amputated just above the knee, at the 13GH.

Unquestionably, it would have been at the 13GH where Les souvenired his second Medtag. The reader may recall that Les Souvenired his first Medtag, that had been attached to him by stretcher bearers and removed when admitted to the hospital ship Gascon, when he was wounded in the arm at Gallipoli.

Given the severity of Les’s April 20th 1916 wounds, and that it is clearly written on the tag that he been administered ‘Morphia’, the author is astounded at Les’s presence of mind to retrieve such an item, which is a very rare ‘souvenir’ indeed.

The 13GH was a very busy hospital, right from the very start of WW1, as can be demonstrated by the following account given by a Nurse Walker who served at the 13GH 1914-1915.

“We arrived at Boulogne on October 30, 1914. The place gave us the impression of being a seething mass of ambulances, wounded men, doctors and nurses: there seemed to be an unending stream of each of them … The sugar sheds on the Gare Maritime were to be converted into a hospital, No.13 Stationary hospital. What an indescribable scene! In the first huge shed there were hundreds of wounded walking cases (as long as a man could crawl he had to be a walking case). All were caked with mud, in torn clothes, hardly any caps, and with blood-stained bandaged arms, hands, and legs; many were lying asleep on the straw that had been left in the hastily cleaned sheds, looking weary to death …. The beds were for stretcher cases, and were soon filled with terribly wounded men, who had just to be put into the beds as they were, clothes and all. As fast as one could get to them the clothes were cut off, the patient washed and his wounds dressed. Some had both legs off, some their side blown away – all were wounded in several places. Doctors and nurses were hopelessly outnumbered, distractedly endeavouring to meet the demands made upon them.”

For some time after the initial amputation, Les remained in a precarious state of health. Official records show that his family were advised on 28th May, and again on 5th June, that Les was “Not Doing Well”.

The day after the second ‘Not Doing Well’ notification, Les was transferred to the 3rd Northern General Hospital, located near Sheffield. Les crossed the English Channel on the Hospital Ship HMHS Cambria.

It is unlikely that the 3NGH provided any ‘special’ treatment that Les had not received at the 3GH-Bolouge, so it must be that Les’s body simply fought-off the infection and he sufficiently rallied that three days later (10th June), Les was formally pronounced as being ‘Out of Danger’. A further three days after that (13th June), Les was discharged from the 3NGH to a Convalescence Home – Longshaw Lodge.

During the First World War, the Duke of Rutland gave-over his shooting lodge (Longshaw Lodge) to be used as a convalescence home for wounded soldiers, and the first patients began arriving there around February 1915.

A local newspaper reported: “Longshaw is ideally situated for such a home, as not only is it within convenient distance of Sheffield, but is placed in the midst of the health-giving moors, and surrounded by beautiful scenery, which will prove a mental tonic to the soldiers who are sent there to recuperate.”

The local paper also went on to give the following description of what it was like for soldiers staying at Longshaw: “The journey from being injured on the front-line, to treatment in a field hospital and eventually a convalescence home was a long one, and the difference in living conditions were a world away from being stationed in the trenches.……………After a midday meal the thirty-five men, who with Sergeant Nixon RAMC occupy the home at present, scatter in various directions, some to take a brisk walk, others to smoke or play cards in the smoking room, where a piano was in constant action. Several of the soldiers possess marked musical gifts, and the strains of dream waltzes were heard, as well as lively ragtime tunes and popular songs. A tournament was in progress in the billiard room, the table having kindly been left there for use by the men.

In the wards, which hold a varying number of beds according to their size, and most which face south, looking out upon beautiful views, a number of the most recently arrived soldiers were resting. One and all seemed full of quiet content and very happy in their new home. This feeling was voiced by an Irishman, who looking up and seeing several snowflakes fall, said he wished they might be snowed in, then they would not have to go.”

It is uncertain what went wrong, probably another infection, but on 6th October, Les had to undergo a re-amputation of his leg at the 3NGH, this time high-up, 6-8 inches below the hip joint.

This was to be the final amputation, and following his recovery from this procedure, on 4th December 1916 Les was transferred to the 2nd Australian Hospital (2AAH) that specialized in the fitting of artificial limbs.

2AAH had only recently been established (August 1916) with, the St Marylebone School in South Road, Southall, Middlesex being taken over by the Australian Imperial Forces as a military hospital.

The Hospital originally been intended as a clearing station, accepting excess patients from the No. 1 Australian Auxiliary Hospital at Harefield Park, but in November 1916 it began to specialize in caring for amputees and the fitting of artificial limbs.

Workshops were set up by the Red Cross to help rehabilitate the amputees, but were too few - only 10% of the patients could be accommodated, making the remainder restless and bored.

Those who could attend, received training in various skills - telegraphy, electrical mechanics, weaving, boot repair, carpentry, etc. - so they would be employable when they returned home. As occupational therapy patients also made rehabilitation embroideries, the Rising Sun being a key image.

Before a soldier was ready to wear and use their artificial multiple fittings a degree of training was required.

As a consequent, between December 1917and December 1918, Les had multiple admissions and discharges from 2AAH, with two periods of furlough-leave being granted to Les.

The first period being from 2nd January 1917 to 17th January 1917. The second being from 21st August 1917 to 10th September 1917.

From personal correspondence it is known that on one of these periods of furlough-leave, Les and some mates went to Wales, probably January 1917.

Another notable outing that Les had while on his second period of furlo-leave from 2AAH, was a visit to Windsor Castle, on 9th October 1917.

In acknowledgement of their sacrifice, during WW1, the King often allowed formally organized groups of wounded soldiers to visit the grounds of Windsor Castle.

On 31st October, Les was admitted for the final time to 2AAH where he received the final fitting and issue of his artificial leg, which would have been a somewhat heavy and hard timber affair.

16th December saw Les’s final discharge from 2AAH, whereupon he immediately was put aboard a Hospital Ship which reached Australia in February/March 1918.

An AIF medical report on Les’s injuries, that apparently was compiled in preparation for his medical discharge, listed his injuries as:

• High amputation Right Thigh (6-8 inches below hip joint).

• Wounds in Right Wrist, Left Elbow, Left Leg.

• The wound in Left elbow joint has caused some paralysis & stiffening with involvement of Ulna Nerve.

• There is considerable wasting of muscles in forearm and hand. Outer two interosseous both show R.D. The outer interosseous shows diminished excitability.

Les was officially medically discharged from the Australian army on 7th May 1918, and so began the post-war era of his life.

POST WW1 LIFE

In December 1917, Les departed England by ship for return to Australia, and arrived back in Brisbane on 17th February 1918.

Due to his right-leg having been amputated in England because of battle wounds, on 7th May 1918 Les was medically discharged from the Australian army.

By all accounts Les was a very quiet, unassuming, kind & generous man, who remained proud of his WW1 service, and would routinely attend reunions with his old battalion pals.

Les’s post-WW1 life essentially comprised of three major focuses, these being, his volunteer work with veteran associations, employment with the Golden Casket, and last but not least, his marriage to Edna, and his children Clare & Peter.

INVOLVEMENT WITH VETERAN'S ORGANIZATIONS

Very soon after his return to Brisbane, Les threw himself into volunteer work with a range of Veterans organizations, such as, The Queensland Central Peace Loan Committee, where he worked as a District Organizer, The Returned Soldiers Labour League, as an Executive Committee Member, and The Limbless Soldiers Association, with whom he was President of the Queensland Branch Committee.

Les was a noted speaker for the QLD Branch of the Limbless Soldiers Association, and was selected on a number of occasions to represent the QLD Branch at inter-state conferences.

There is a newspaper article that appeared in 17th September 1922 edition of the Daily Mail – Brisbane, giving a brief report of a Limbless Soldiers Association conference recently held in Melbourne, at which Les represented the Queensland Branch. The heading of this article was: “Six men, and five legs”.

An article that appeared a day earlier in the Adelaide Observer provides an explanation for the Daily Mail heading. It states that of the six Limbless Soldiers Association members who appear in the photograph, they only had five real legs between them!

All the organizations that Les did volunteer work for, shared a similar objective, this being to advocate on behalf of returned servicemen, in the areas of employment opportunities, pensions entitlements, and travel concessions etc.

There was a particular issue, which going by the number of newspaper articles that appear in which Les is reported making comment on the subject, was for limbless & blind veterans to receive concession fares for tram transport.

One would have thought that the authorities would have had no hesitation in granting such a small thing to those that had sacrificed so much, but this was not the case.

In one newspaper article, Les argues that because of their incapacities, limbless & blind veterans were unable to walk very far, and were thus heavily reliant upon using public transport to get about …..and, because of this, the authorities refusal to grant concessional fares was akin to the authorities “taxing” these veterans because of their war-wounds.

Les appealed and argued for years, before the authorities (in the instance, the Brisbane City Council), finally agreed to allow limbless & blind veterans concession fares for transport on Brisbane trams.

Eventually in 1928, Les was successful, and concession fares were granted to Limbless/Blind, and later TB invalid veterans.

GOLDEN CASKET

While continuing with volunteer activities, in 1921 Les received an appointment to full-time employment as a clerk with the then recently established Golden Gasket Lottery organization.

The Golden Casket started in 1916, when the Queensland Patriotic Fund asked if they could run an Art Union for the Repatriation Fund of the Queensland War Council. The first Casket tickets went on sale in December 1916.

As cash prizes were at that time prohibited by law, it was decided that the jackpot prize would be £5,000 in solid gold. Back then, £5,000 was the equivalent to 30 years of a full-time salary.

So as to promote the lottery, the jackpot prize was daily placed on display in a jeweler’s window, with the gold being in a small wooden casket, hence the name of the lottery.

It was successful in raising funds and a second Casket was also run for the Patriotic Fund, then three Caskets were run to fund the building of homes for War Widows by the Anzac Cottage Committee.

The sixth Casket run gave the profits to the Hospital for Sick Children (now known as the Royal Childrens’ Hospital), which was in urgent need of funds for repairs and further development at a time when donations from the public were more difficult to obtain.

From 1920 the Government took over the running of the Casket with the profits being used for funding Public Hospitals, Maternity Hospitals and Baby Clinics.

The Royal Women’s Hospital was funded by the Casket at a cost of 200 thousand pounds.

By 1938, 93 maternity hospitals and 122 baby clinics had been provided by the profits of the Casket.

The money was used to provide free hospitals in Queensland and this was important as previously hospital care was not free. Previously, the richer persons provided charitable entry or you paid for the services provided. The hospitals were always trying to gather donations.

With the Casket there were many small donations from many people rather than larger donations from the few. The general public embraced the concept of the Casket, as not only was there a possibility of winning the first prize, which was a number of years of wages for a tradesman for a small investment, it didn’t matter if you didn’t win, as after all “you still got the hospital!”.

100,000 tickets were sold in each Casket. You could buy a half, quarter or one-fifth share in a ticket and originally a barrel containing 100,000 marbles was used to draw the prizes.

In the first fifty years of the Casket’s operation, it contributed significantly to the sick and needy with $73 million dollars being used for the hospital and health system and $200 million being returned as prizes.

Les clearly enjoyed being part of this significant community orientated organization, for he stayed working with the Golden Casket for the remainder of his working life, and it was at the Golden Casket that Les met his wife-to-be, Edna Coren.

MARRIAGE TO EDNA MARIE COREN (1903-1977)

Perhaps it was due to a combination of throwing so much energy into work (paid & volunteer), that together with possible self-consciousness of being a limbless man, it was not until the early 1930’s that Les met the woman who he would eventually ask to be his wife, and was the love of his life.

On 23rd June 1934 Les (age 41) and Edna Marie Coren (age 31) were married at the Holy Family Church in Indooroopilly.

The union between Les & Edna proved to be a tremendously loving and long lasting relationship, and they remained at their home in Holland Park all their married life, where they both aged gracefully into their “Autumn Years”.

Les died in 1970 aged 77, and Edna following in 1977 aged 74.

Submitted 13 June 2023 by Tony Young