MERSON, David

| Service Number: | 4660 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | 30 September 1915 |

| Last Rank: | Private |

| Last Unit: | 26th Infantry Battalion |

| Born: | Stamfordham, Northumberland, England, 1889 |

| Home Town: | Palmwoods, Sunshine Coast, Queensland |

| Schooling: | Royal Grammar School, Newcastle-on-Tyne, England. |

| Occupation: | Fruit Farmer |

| Died: | Died of wounds, France, 18 April 1918 |

| Cemetery: |

Vignacourt British Cemetery, Picardie Plot I, Row B, Grave No. 9. |

| Memorials: | Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour, Nambour Heroes Walk, Nambour Maroochy Shire War Dead Memorial, Palmwoods WW1 Roll of Honour |

World War 1 Service

| 30 Sep 1915: | Enlisted AIF WW1, Corporal, 4660, 26th Infantry Battalion | |

|---|---|---|

| 12 Apr 1916: | Involvement Corporal, 4660, 26th Infantry Battalion, --- :embarkation_roll: roll_number: '15' embarkation_place: Sydney embarkation_ship: RMS Mooltan embarkation_ship_number: '' public_note: '' | |

| 12 Apr 1916: | Embarked Corporal, 4660, 26th Infantry Battalion, RMS Mooltan, Sydney | |

| 18 Apr 1918: | Involvement Private, 4660, 26th Infantry Battalion, --- :awm_ww1_roll_of_honour_import: awm_service_number: 4660 awm_unit: 26th Australian Infantry Battalion awm_rank: Private awm_died_date: 1918-04-18 |

Help us honour David Merson's service by contributing information, stories, and images so that they can be preserved for future generations.

Add my storyBiography contributed by Stephen Brooks

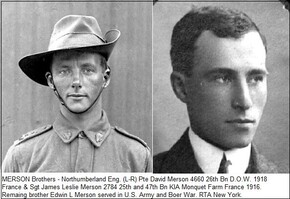

David Merson was born England during 1890. He was the son of Rev. David Merson, D.D. and Jessie Margaret Merson (nee Leslie) from Huntly in Aberdeenshire. David was educated at Royal Grammar School, Newcastle, and trained in Life Insurance. He emigrated from England in about 1908 aged 18 to farm pineapples at Palmwoods in Queensland. His older brother James later joined him.

His brother, 2784 Sergeant James Leslie Merson 47th Battalion AIF, was killed in action on 31 August 1916, near Mouquet Farm, aged 32.

David enlisted in Brisbane with the 26th Battalion and left for the Middle East in April 1916.

On 5 November 1916 was witness to the death of his cousin Lieut. Douglas Leslie at Flers, which he recorded in a moving letter to his aunt.

David was wounded in action 22 March 1917, and was admitted and transferred to 45th C.C.S. 23 March 1917 – with gunshot wounds to the left arm, and shrapnel wound to left wrist. He was evacuated to England and admitted to Kitchener war Hospital, Brighton. He returned to France during October 1917.

David was wounded in action, the second occasion, on the 16 April 1918 in the vicinity of Dernancourt. He died of wounds two days later at the 20th C.C.S. - shrapnel wound, penetrating chest. He had named his aunt, Martha Elizabeth Leslie, as next of kin in place of his brother James. Both his parents were deceased. David left an English fiancée Mary Gillies.

While recuperating at hospital in 1917, David Merson wrote some quite descriptive letters home. One written to his brother-in-law Athole Murray on 19 April 1917 is a wonderful soldier’s description of the fighting in France.

"I had enough experience of war crowded into the six months I was at the front to satisfy the biggest glutton under the sun. I was on the Somme all the time, except for a short time at Ypres in October. Any man who has been in France will always associate the Somme with mud-mud everywhere, cold, sticky & deep. Besides the mud, the heaviest part of the fighting always took place on the Somme. In November I took part in a charge on the German trenches, & we failed because the artillery failed to cut the barbed wire entanglements between our lines & Fritz's. The result was that the battalion I belong to got wiped almost out of existence. I was one of the lucky ones & came through it without a scratch. When you read in the newspapers about our men charging the German trenches & capturing them do you ever realise what the men have to go through who take part in it. The loss of 25% of the strength of a unit in a charge is considered very low while 50% is common & up to 70 & 80% often happens. A charge is preceded by a few minutes intense bombardment in 'No Mans Land' to wipe out any snipers or working parties that might be knocking about & also to prevent the enemy from leaving their trenches to meet us. No one could possibly realise what an intense bombardment is like without seeing one. All the big guns for miles around play onto the spot to be taken & probably 1000 guns are throwing shells into a space of 100 yards as fast as they can fire. High explosive shells bursting, throw up clouds of mud & dirt, shrapnel bursting in the air & pieces flying about everywhere & the whole air is grey with smoke & full of the smell of powder. You cannot distinguish the individual firing of the guns as it is just one loud rumbling noise like thunder, but louder. Then the barrage lifts from No Mans Land on to the enemy's front trenches, so as to prevent the men in the trenches from raising their heads above the parapets. Then the attackers leap out of their trenches with fixed bayonets & carrying their machine guns. Then hell opens up. The enemy guns start to shell No Mans Land for all they are worth, & machine guns rattle out from the enemy's positions. Perhaps the first wave of men only get a few yards & are mown down with machine gun fire, like a scythe going across a field of corn. All go across at a slow trot or walk - the ground is heavy, being all churned up & it is one mass of shell holes which of course have to be avoided. Your mate alongside of you falls forward without a groan - he is dead. Just in front of you a few yards a high explosive shell bursts & you await the end calmly, but not this time & you notice that one man perhaps half a dozen, have disappeared & you know that they are buried & will never be seen again, unless the next shell uncovers their bodies! Then you get within 25 yards of the enemy's trench & the barrage lifts from his front trench on to his support trenches & you rush forward with a wild shout of joy. What living men are left in the enemy's trench are as much demoralised by that shout - the shout of victory - as by the awful bombardment they have just been through. They throw up their hands & cry "Mercy, Kamerad" & you see that awful look of despair & misery on their faces & no matter what oaths you had previously sworn against these men, or what revenge you had promised yourself when you came face to face with them, you feel that now to satisfy those desires would be cowardly, unfair, & unsportsmanlike. You search them for souvenirs then send them back under escort & make them carry wounded back with them. Then the trench is searched for dug-outs which are usually packed with men. You call for them to come out & most of them obey, but if all persuasion fails, you throw one or two bombs down the stairs, for in war unnecessary risks cannot be taken when it is your life or theirs. You hear groans at the bottom of the dug-out & later go down to clear the place of its human debris. All hands set to work to build up the trench, knocked about by their own guns, - to face it about so as to suit their own needs. Then you prepare for the counter attack."

David’s next of kin, his aunt, Martha Leslie, also lost three sons during WW1.