ROWLAND, Frederick Llewellyn

| Service Number: | 7343 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | 15 September 1916, Melbourne, Victoria |

| Last Rank: | Private |

| Last Unit: | 8th Infantry Battalion |

| Born: | Lawrence, Victoria, Australia, 17 March 1885 |

| Home Town: | Clunes, Hepburn, Victoria |

| Schooling: | Central State School Ballarat |

| Occupation: | Drover/Grazier |

| Memorials: |

World War 1 Service

| 15 Sep 1916: | Enlisted AIF WW1, Melbourne, Victoria | |

|---|---|---|

| 19 Feb 1917: |

Involvement

AIF WW1, Private, 7343, 8th Infantry Battalion, Enlistment/Embarkation WW1, --- :embarkation_roll: roll_number: '9' embarkation_place: Melbourne embarkation_ship: HMAT Ballarat embarkation_ship_number: A70 public_note: '' |

|

| 19 Feb 1917: | Embarked AIF WW1, Private, 7343, 8th Infantry Battalion, HMAT Ballarat, Melbourne | |

| 8 Dec 1920: | Discharged AIF WW1 |

1919 - 1920

Letter to his Mother Jane Rowland nee Huston

29th November 1919

Mrs. J Rowland, Canterbury Street, Clunes, Vic

Dear Madam, Information has been received from A.I.F Headquarters, London, to the effect that your son, No 7343, Private F. L. Rowland, 8th Battalion, proceeded to America per s.s. "Celtic" from Liverpool on 25th August for the purpose of instruction in agriculture and pig-raising methods. Upon receipt of advice that he has re-embarked for Australia you will be promptly notified.

Yours faithfully, Major Officer i/c Base Records.

25 August 1919

First name(s) F L

Last name ROWLAND

Title PTE

Occupation H M FORCES, Age 31 y 5 months, place of birth Clunes

Departure year 1919

Departure day 25

Departure month 8

Departure port LIVERPOOL

Destination port NEW YORK

Destination NEW YORK

Country United States

Destination country United States

Ship name S S CELTIC

Ship official number 113476

Ship master's first name F B

Ship master's last name HOWARTH, Shipping line WHITE STAR LINE

City LIVERPOOL, Ship destination port NEW YORK

Ship destination country USA

Ship registered tonnage 20904, Number of passengers 123

Returned to Sydney New South Wales, Australia by ship on 12/10/1920

Departed Port of San Francisco United States

on the S S Sonoma

passenger list Frederick Rowland, 76 males, 38 females, 21 children, 37 crew members.

Submitted 31 March 2022 by Gail Stapleton

Missing Person

If anyone can tell me his death date and location of burial I would really like to know. Thanks.

Submitted 31 March 2022 by Gail Stapleton

Death Date & Burial

If anyone can tell me his death date and location of burial I would really like to know. Thanks.

Submitted 7 October 2015 by Gail Stapleton

Biography contributed by Evan Evans

From Ballarat & District in the Great War

Genealogy is a fascinating subject. It can be immensely satisfying to see where our family fits into an historical timeline. But it can also be just as frustrating, with missing information causing gaps that only interpretation can fill. In tracking our servicemen and women of the Great War, I often rely on genealogies compiled by their families, although I frequently have to start a new tree to confirm the information. When it came to Fred Rowland from Clunes, a significant amount of research had already been done. But Fred was elusive and he even stumped his family…

The son of Welsh and Irish immigrants, Frederick Llewellyn Rowland was born on 17 March 1885 at the small gold-mining settlement of Lawrence, which was then situated between Clunes and Smeaton. He was the youngest of six children born (after a gap of some seven years) to David Rowland and Jane Huston.

Born at Trefforest in the Welsh Rhondda Valley, David Rowland was 20-years-old when he arrived in Melbourne on 7 December 1861. Coming from a mining background, he had initially found ample work in the thriving gold mines around Clunes. His wife, who he married at Ballarat on 28 April 1869, came from Garvagh, a rural village in the foothills of the Sperrins and Lower Bann Valley, in the Irish county of Londonderry. It was certainly a vibrant mix of Celtic cultures.

At the time of Fred’s birth, his father was employed as the weir keeper at Lawrence, a position that was overseen by the Clunes Waterworks.

It was not to be an easy year for the David and Jane Rowland, with the death of their 14-year-old son, David Davies, on 1 September. Just two weeks later, on 16 September, six-month-old baby Fred was baptised – it was an important step with the ever-present fear of infant mortality. As a result, there was a significant gap in the family that Fred grew into. There was only the one girl, Sarah, (who was known as Sissie) and, no doubt, she would have doted on her little brother.

As a boy, Fred attended the State School at Allendale. It seems he was set to follow his older brother, John Francis, into the teaching profession when, in January 1902, after a competitive examination, it was announced that he had won a position as a monitor at the Dana Street (Central) State School in Ballarat.

The death of David Rowland on 10 November 1903 potentially forced a change in his youngest son’s career aspirations. For many years the family had lived in the caretaker’s residence, a large weatherboard home at Lawrence, but David’s death and the loss of the family’s breadwinner necessitated a move to Canterbury Street in Clunes and Fred was soon working as a general labourer.

As time passed, Fred turned to farming, although he would elevate his status by using the more salubrious term, grazier – and worked predominantly as a drover.

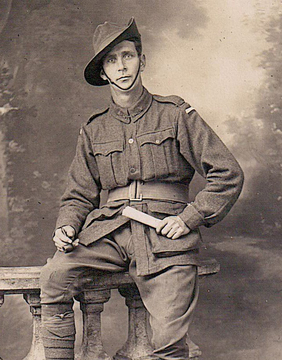

War was to offer Fred a new and stable occupation. On 2 September 1916, he presented himself to local doctor, Arthur Blackett-Forster, who was the medical officer designated to oversee examinations of potential recruits at Clunes. Fred cut an impressive figure: he was a quarter inch over 6-foot tall, weighed 164-pounds and could expand his chest to 39-inches. It was also important to record other physical attributes, and so it is that we know that Fred had blue eyes and brown hair, with a distinctly fair complexion. He had a vaccination mark from childhood, a number of scars – including one on his left knee – and asked that his religious affiliation be entered as Church of England. Blackett-Forster passed Fred as fit subject to his teeth being attended to and he was sent to Melbourne to be re-examined. On 13 September, Fred was passed fit and signed his name to the oath drawn up for all members of the AIF.

Fred joined the 23rd Depot Battalion at Royal Park on 29 September and was posted to A Company. His previous military experience was said to have been ’64 days in Commonwealth Forces,’ a negligible term compared to his intended undertaking. However, he was to spend five-months training in Victoria before he was ready to embark for Europe. During that period he was attached to several units including the 4th reinforcements to the 38th Infantry Battalion and the 18th reinforcements to the 24th Infantry Battalion.

During leave home, the people of Lawrence gathered at Berry Vale, the property of grazier, Mr Robert Wilson, on 21 November to farewell Fred Rowland. He was the recipient of a wristlet watch and several personal compliments from the audience. Everyone then enjoyed of a delicious supper provided by Alice Wilson, and rounds of games and an entertainment that included songs and recitations. The singing of Auld Lang Syne was an emotional end to what had been a memorable evening.

Finally, on 10 January 1917, Fred joined the 24th reinforcements for the 8th Infantry Battalion with the rank of lance-corporal. He embarked from Melbourne on 19 February onboard HMAT Ballarat – it was to prove an eventful trip to England.

Early in the voyage the Ballarat stopped at Cape Town to take on food, water and coal. The soldiers onboard were left with an indelible impression of Table Mountain and spoke at length of their later stopover in Sierra Leone. However, due to the poor quality South African coal the Ballarat could not maintain her usual speed and the convoy was forced to slow in order to stay with the troopship. It was a dangerous time, with the German government announcing a return to the previously unrestricted submarine warfare that had resulted in the sinking of the Lusitania on 7 May 1915.

On ANZAC Day 1917, German submarine UB32, was lying in wait for Allied shipping off the Cornish coast. Spotting the Ballarat, her commander fired a torpedo at the troopship, just as the Australians were preparing for commemorative services. Thanks mainly to the actions of the quick-thinking captain there was no loss of life and tributes later flowed for the remarkable discipline of the troops. As strains of ‘Australia Will Be There’ rang out over the water HMS Lookout and HMS Drifter came to the rescue and, after taking onboard some survivors, attempted to take the stricken vessel in tow, but the Ballarat sank the following day at 4.30am.

It was noted in an English newspaper that ‘every pet was rescued, with the exception of some of the ship’s cats…over the side went Bill Anzac (an Australian parrot in a cage), a grey squirrel had the run of the raft, and a fox terrier and her puppies are now guests of the officers on a destroyer.’ The homeward bound mails were also saved; as was the Bandmaster’s cornet.

Possibly the only casualty of the incident was Private William D’Angri from Ballarat. Lifeboat drill required that the men remove their boots before sliding down the ropes in order to avoid painful contact with the fingers of the men below. The soldier who followed young D’Angri had failed to obey orders making a bruising impact on the boy’s fingers. It was only luck that D’Angri’s timing was right and his cobbers were able to grab him and pull him onboard the lifeboat. This also explains a newspaper report that ‘[the troops] were landed with promptness and despatch, and soon set foot in England for the first time without their boots.

King George V later congratulated the captain of HMAT Ballarat Commander G. W. Cockman DSO for his fine seamanship in avoiding a potential disaster. Mr Andrew Fisher the High Commissioner for Australia forwarded a message to the men, ‘Allow me to express our admiration of your soldierly bearing and cool courage in the face of death as demonstrated on Anzac Day. Australia rejoices that you are all alive today, awaiting the hour and the opportunity to pay back your score.’ (She was salvaged in 1957 in an attempt to recover her valuable cargo of copper ingots, antimony ore and bullion).

For Fred Rowland – and everyone on the Ballarat – this was an unforgettable moment of the war. HMAT Ballarat was one of just five Australian transports sunk during the course of the war, but was the only one that had been carrying troops at the time. ’ His welcome to the Old Dart was certainly a memorable one!

The men were all landed safely at Devonport later the same day. They travelled straight through to Durrington on the edge of the Salisbury Plain, a trip of nearly 140-miles. Fred was then posted to the 2nd Training Battalion. He was still at Durrington when, on 8 June, he was found to have misled the Dental Officer by saying he didn’t have a set of false teeth. Apparently, he had given his set to another soldier… Lieutenant-Colonel John Walstab took a poor view of this indiscretion and awarded Fred 168-hours of Field Punishment No2 (which often involved being placed in fetters and handcuffs) and fined him £1/15.

After attending a course of instruction at the School of Farriery at Romsey from 13 August until 16 November, Fred qualified as a shoeing-smith. He then returned to the 2nd Training Battalion, which was then stationed at Sutton Veny.

When he was granted leave from 28 November, Fred took the opportunity to visit his extended family in Wales and Ireland. However, when he became ill during the journey not only was his leave ruined, but it was to eventually lead to him being court-martialled. According to Fred, he had reached Port Talbot in Wales and was preparing to leave for Castlereagh in Ireland when he fell ill with acute tonsillitis that led to severe bronchial catarrh. A Doctor Hellyer was called in and, as the town did not have a hospital, he ordered Fred to stay in bed. He provided him with a certificate which was duly forwarded to Fred’s company commander. Fred also wrote to the company clerk, explaining the situation, that he was unable to travel and would return to his unit as soon as he was able.

On 28 February 1918, Fred was finally fit enough to return to duty and the doctor gave him a second certificate to cover him for his time absent from his unit. After returning to camp on 1 March, Fred presented the certificate and was then placed on light duties for four days.

Unfortunately, the authorities had already declared Fred to be an illegal absentee during a Court of Enquiry, which was held at No5 Camp Sutton Veny on 28 January. As a result, a District Court Martial was convened on 26 March. Fred Rowland plead Not Guilty to a charge of being Absent Without Leave from 6 December 1917 to 1 March 1918. Although the original letter from Dr Hellyer had been lost, they were able to secure testimony that confirmed Fred had been under his care during the time he was absent. His defence concluded that Fred had also done everything in his power to let the authorities know he was ill and unable to return to camp. With the formalities attended to, Fred was quickly found not guilty of the charge and returned to duty.

On 7 April 1918, Fred left Sutton Veny for Southampton, where a ship was waiting to take reinforcements to France. He arrived at the Australian Intermediate Base Depot at Le Havre the following day. When he reached the 8th Battalion in the Strazeele Sector on 21 April, the race to save Hazebrouck and the Channel Ports from the advancing Germans was over. The men of Ballarat’s famous “blood and bandages” battalion had been instrumental in steadying the line and thwarting the potential success of the enemy’s Operation Georgette. However, when Fred arrived there was a small contretemps in progress – a group of men, ‘using their notorious initiative,’ had raided a nearby brewery in Hazebrouck. For two days much of the battalion was reportedly incapacitated. It must have been an interesting initiation for Fred Rowland.

The 8th Battalion spent the next climactic months in the Strazeele Sector. On 23 June, Fred was forced to report sick – he was admitted to the 2nd Australian Field Ambulance before being transferred to the 64th Casualty Clearing Station (1/1st East Lancashire) at Watten. He was out of action for over a week, but there was no indication as to the diagnosis of his illness.

Fred rejoined his unit on 4 July, a pivotal day for the AIF on the Western Front. The Battle of Hamel drew on all the aspects of modern warfare and proved to be a masterclass of leadership on the part of General John Monash. Word of the success spread quickly up and down the line. It provided the impetus for the coming Battle of Amiens and the launch of the Allies own offensive and the advance on 8 August 1918 was to be the most successful single day of the war for the Allies and was to become known as “the black day of the German Army.” The 8th Battalion played a significant role in this action and was to earn two Victoria Crosses in the process.

Fred Rowland fought through these monumental weeks with the 8th Battalion continuing in operations late into September. When the guns fell silent on the Western Front on 11 November, the men were at Bazuel in Northern France.

Arriving later in the course of the war meant that Fred was going to be kept waiting for a return voyage home – it was very much a case of first in, first out. However, this then afforded him the prospect of vocational study as a part of the AIF Education Scheme. During May and June 1919, Fred was granted leave (with full pay and subsidies) to attend a course in Veterinary Science held at Edinburgh University. His leave was extended for a further month to enable him to continue at the university studying husbandry.

At the completion of this phase of his study, Fred was given an even greater opportunity. On 31 July, he was granted six months leave to travel to America to study modern agricultural methods in irrigation and pig-raising. He sailed for the USA on 25 August onboard the SS Celtic.

As it eventuated, Fred was to spend a full year in America, with much of his time spent around Sacramento in California. He finally sailed home to Australian on 21 September 1920. After returning to Clunes and his mother’s home in Canterbury Street, Fred settled into a new job as a dealer. As part of returning to a normal life, Fred played for the Ullina team during the 1920-21 cricket season and proved to be a very capable bowler.

Life, however, was about to take a quite dramatic turn for Fred Rowland and it was all for the love of a woman.

One of the pubs in Clunes, the All Nations Hotel on the Talbot Road, was run by Mary and William Mooney. The couple lived in a rather dilapidated house adjacent to the hotel and it was known that Mary ‘had trouble with her husband.’ Ongoing problems reached a climax on 31 December 1921. With her two small children in hospital suffering from diphtheria, her own health declining due in part to their living conditions (she had complained about the state of the roof and floors) she declared to the local constable, John Featherston, that her husband ‘could have the hotel and the children, too.’

Around the same time, Fred Rowland was involved in a very serious accident when he was travelling between Clunes and Tourello. He was driving a jinker (a small, two-wheeled cart) when he was overtaken by a motorcar – the car struck the jinker with such force it was completely smashed. Fred was thrown to the ground, suffering ‘very severe injuries.’ Although he eventually recovered, there was no mention of the person responsible for the collision ever being charged for the accident.

Soon after this incident, Fred left Clunes. It appears that he and Mary Mooney (who was born Marie Gertrude West) had decided to throw their lot in together and start afresh. Their relationship was confirmed by the birth of their daughter, Lesley, at Footscray in 1922. They then travelled to New South Wales and settled in Crows Nest where Fred worked as a driver.

A second daughter, Bobbie, was born in November 1926. Sadly, she died at Annandale on 29 April 1927 when she was just five-months old.

In the mid-1930’s, Fred and Mary were living at Naremburn on the lower North Shore of Sydney. They lived there quietly for some time before a move to Chatswood in the latter years of the decade. In November 1937, he was appointed as an impounding officer and ranger for the Municipality of Willoughby. Intriguingly, when this appointment was announced, his name was given as Llewellyn Rowland, which indicates perhaps that he had modified his name to seek some form of anonymity.

Following Mary’s early death on 29 February 1940 (she was just 57), Fred continued to live in Chatswood and maintained his position with the council as a ranger for many years.

The last time Fred appears in the records was in 1963, when he was retired and living at Strickland House in Vaucluse Road, Warringah. At the time, Strickland House was being used for respite and long-term care for the elderly.

Unfortunately, from this point, Frederick Llewellyn Rowland disappears. There is no record of his death or burial and no further entry in electoral rolls. It is safe to assume that he died soon after this last entry at Warringah. But why was there no death recorded? With genealogy, as with all record keeping, all it takes is one human error to create an unfillable blank space. It is possible that Fred Rowland died at Strickland House and the death certificate was filed with his medical records and not registered. But why does his name not appear in any of the nearby Sydney cemeteries? Were his remains cremated and taken by his family? I have noted that not all searchable databases contain these records. So, where is Fred? We would all love to know!

Biography

Son of Jane Huston and David Rowland of Lawrence Weir, Victoria, Australia

Discharged from Service on 08 Dec 1920