MALIN, Leslie John

| Service Number: | 2109 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | 19 June 1916 |

| Last Rank: | Corporal |

| Last Unit: | 39th Infantry Battalion |

| Born: | Ballarat, Victoria, Australia, June 1881 |

| Home Town: | Ballarat, Central Highlands, Victoria |

| Schooling: | Dubbo Public School, NSW, Cambrian Hill State School, Victoria, Australia |

| Occupation: | Manufacturer (Malin's sauce) |

| Died: | Wounds, 61st (2/1st South Midland) Casualty Clearing Station, Veqcuemont, France, 1 September 1918 |

| Cemetery: |

Daours Communal Cemetery Extension, France Plot VIII, Row B, Grave No. 37 |

| Memorials: | Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour, Ballarat Old Colonists' Club, Magpie State School Honor Roll Book, Magpie State School No. 2271 Honour Roll |

World War 1 Service

| 19 Jun 1916: | Enlisted AIF WW1, Private, 2109, 39th Infantry Battalion | |

|---|---|---|

| 25 Sep 1916: | Involvement Private, 2109, 39th Infantry Battalion, --- :embarkation_roll: roll_number: '18' embarkation_place: Melbourne embarkation_ship: HMAT Shropshire embarkation_ship_number: A9 public_note: '' | |

| 25 Sep 1916: | Embarked Private, 2109, 39th Infantry Battalion, HMAT Shropshire, Melbourne | |

| 1 Sep 1918: | Involvement Corporal, 2109, 39th Infantry Battalion, --- :awm_ww1_roll_of_honour_import: awm_service_number: 2109 awm_unit: 39th Australian Infantry Battalion awm_rank: Corporal awm_died_date: 1918-09-01 |

Help us honour Leslie John Malin's service by contributing information, stories, and images so that they can be preserved for future generations.

Add my storyBiography contributed by Evan Evans

From Ballarat & District in the Great War

Cpl Leslie John Malin, 39th Infantry Battalion AIF

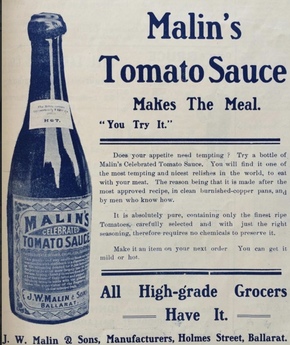

At the turn of the Century Ballarat could claim one of the finest tomato sauce brands in Victoria. The sauce produced by J. W. Malin and Sons was so highly sought after, the factory struggled to keep up with demand. However, a series of tragic events was to effectively wipe the business from existence.

Leslie John Malin’s birth in June 1881 was a happy arrival. His parents, John William Malin and Mary Jane Adams, had been married just three years and Les was their second son. He was descended from a long line of doers – men who ran successful businesses incorporating very specific talents. There were butchers and bakers, and publicans, but a decided lack of candle-stick makers. The Malin family came from Bermondsey, which was, appropriately, a centre for manufacturing in London.

William Francis Malin was the first of the Malin family to arrive on the goldfields. His future wife, Christina White, was originally from the port city of Hull in Yorkshire, where her father had been a publican. They were married at St Peter’s Church of England, Melbourne, on 4 April 1854. Although he had trained as a bricklayer, William Malin quickly recognised a greater opportunity; the miners required two things: alcohol and food. In establishing a butcher’s shop in Long Gully at Magpie, south of the main diggings at Ballarat, William was able to corner the market and they did a bustling trade.

An advertisement in the Ballarat Star on 26 February 1863 certainly painted an interesting picture.

“WANTED a Boy for a Butcher’s Shop and Store;

One accustomed to killing. Enquire at William

Malin’s, Storekeeper, Long Gully, Magpie.”

At the same time there was a Londoner by the name of Edward Green Adams operating a butcher shop in nearby Sebastopol. His marriage to Lavinia Ada Mead at Buninyong on 24 June 1856, resulted in a delightful anecdote.

‘…Owing to the heavy rains Mr. and Mrs. Adams had difficulty in reaching their home after the marriage ceremony, the surrounding country being very boggy, and he had perforce to adopt the expedient of carrying his bride on his back until the more boggy part of the journey was accomplished…’

Lavinia Mead came from the prosperous manufacturing town of Tiverton in Devon, where her father, Samuel, had been a tailor. The Mead family had been in Tiverton for several generations.

The butcher shop in Sebastopol was just one aspect of Edward Adams’ business ventures. They dabbled briefly in the hotel trade, before building successful butcher shops at Geelong and Ondit near Colac.

Mary Jane was Edward and Lavinia’s first-born daughter.

In 1875, the Adams family moved to New South Wales and settled at Gundagai where they farmed 640 acres at Burra Creek. After seven years on the land, they moved to Dubbo.

The connection between the two families, established during those early years at Magpie, was maintained even after Edward Adams moved his family to New South Wales. On Thursday 10 October 1878, at the Wesleyan Church in Gundagai, John William Malin (William and Christina’s eldest son) and Mary Jane Adams were married.

Initially, John and Mary made their home in Ballarat, where their first son, Francis William, was born on 16 September 1879. Les followed two years later. Soon after his birth, the family moved to Dubbo to be closer to Mary’s parents.

The Malin family grew during their time at Dubbo, with the subsequent births of six more children. Two little girls died in infancy, leaving Frank, Les, Lavinia, Florence, Herbert and Dorothy. When John Malin wasn’t working as a commission agent he was busy helping to build the Methodist Church as a junior circuit steward in the region.

It was at the Dubbo Public School that Les Malin began his education.

While his son was building a life in Dubbo, William Malin was earning a degree of celebrity over his sauces and jams. The sauce was in great demand all over the colony and he was struggling to meet demand. In 1885, after four years of using primitive appliances in his small factory, William upgraded to steam power and installed large tin-lined coppers. The changes enabled him to produce 3000 bottles of sauce a day – ‘even this large number is not more than equal to the demand.’

In July 1894, Les was enrolled at the Cambrian Hill State School midway through Grade V. His father was named as his enrolling parent or guardian, and it was stated that he was a manufacturer of Magpie. It appears that Les had been sent to stay with his grandparents during this time as his father was still residing in Dubbo. It wasn’t until early February 1896, that it was announced with great regret that John Malin was leaving the Dubbo district.

That same year, Les completed his education at Cambrian Hill and joined his father and elder brother in the expanding sauce business then known as J. W. Malin and Sons. John Malin immediately set about establishing the sauce manufacturing plant in Holmes Street in the magnificent building that had once housed Grenville College. The two-storey brick and stone building that backed onto the Gnarr Creek, had previously been used by cordial manufacturer, John MacDonald.

In spite of the building once housing one of the finest schools in the colony, the area around the site was quite rough. There were several factories and even a ‘house of ill-fame.’ The residence, which fronted directly onto Holmes Street, did, however, exhibit all the charm and grandeur expected from a Henry Caselli design. And the tomato sauces produced at the adjacent factory soon stood proudly alongside the iconic brands Rosella and (later) White Crow.

The business was dealt a devastating blow when fire ripped through the factory on 25 February 1899. When the signalman in the box at the Macarthur Street crossing noticed smoke issuing from a wooden cottage at the rear of the factory, he immediately alerted the City Fire Brigade. By the time crews from the City and Ballarat East brigades reached Holmes Street, the fire was almost out of control. The engine house, bottling room and stables were alight and a high wind fanned the flames into the factory roof. Water played onto the iron roof heated to boiling point and the firemen were forced to retreat to avoid being scalded. There was a real concern that the factory’s boiler would explode. It was only when part of the roof collapsed that they were able to get the upper hand.

Although the main building had been insured for £400, there was no insurance on the stock.

It was noted at the time that next to the burned-out cottage ‘stands uninjured a relic of old Ballarat of the early fifties. This is the stone-faced building mentioned in Withers’ "Chronicles of Ballarat,” published some years since in the columns of The Star. The building once occupied the site of the present Bank of Victoria, in Lydiard street, and was the bank of that time, faced the old police and military barracks, and at the date of the Eureka Stockade trouble was fortified and occupied by police or military to intercept the expected approach of an Armed contingent of diggers from Creswick. When the present bank was erected the materials of the old one were removed to Holmes street and re-erected there…’

The admission of William Malin to the Kew Lunatic Asylum on 16 March 1901 proved to be a difficult time for the family. He was diagnosed as suffering from senile dementia, but it is not known if the factory fire contributed to his sudden mental demise. The admitting doctor was concerned that ‘his bodily health on admission was in an unsatisfactory state.’ It seems that either the 74-year-old was already suffering from pneumonia or developed it within days of arriving at Kew. His death on 9 April 1901 went virtually unmarked in Ballarat.

Sadly, the family was to undergo further upheaval.

John Malin had a poor history around horses. On 28 November 1889, he had been driving his buggy about a mile out of Dubbo, when his young horse became spooked. It lashed out kicking the dashboard that splintered and John was hit in the face by splinters of timber. He suffered several nasty injuries and was found ‘insensible’ on the road.

Then, in January 1890, he went out for a drive in his wagonette. When he took a corner too sharply, John was thrown out onto the road. On this occasion he escaped with a cut to his leg and a severe shaking.

Working with horses, however, was a necessary part of operating the Malin factory and John Malin could often be seen driving around Ballarat. Moving along Armstrong Street in the centre of the town on 12 February 1906, he once again found himself struggling with an unmanageable horse. At the best of times, horses can be unpredictable and, on this occasion, the horse had only been recently purchased, meaning that John Malin had little knowledge of what could initiate a reaction. As they neared the tramway, the horse began to canter. In attempting to jump off the shaft board and grab the horses head, John became entangled in the reins and fell. The wheels of the heavy vehicle ran directly over his body, causing catastrophic crush injuries. He was transported to hospital in a cab and was unconscious when admitted. From the outset ‘there was no hope of his recovery,’ but he was able to revive enough to recognise Mary and their children before his death.

In order to tie up the estate, the legal paperwork included a list of ‘good debts’ owing that showed the Malin business had outlets all over Victoria.

The task of maintaining the factory and business now fell to Les, who largely took over its day-to-day running. Productivity and distribution continued to grown and Les added to the reputation of J. W. Malin and Sons.

At 25, Les had developed into a thoughtful, intelligent man, who was a lover of books and of fine horseflesh. He was both strong and self-reliant, with an aptitude for business. To the wider world, more importantly, Les was also that most prized of Australian individuals being described as ‘an all-round sportsman,’ running with the Ballarat Harriers and rowing with the Wendouree Rowing Club. Although he was only of average height (5-feet 6-inches), Les had a muscular build and a way of standing that commanded attention. His noticeably grey eyes were only partially obscured by the spectacles he needed to correct his poor sight. As was the fashion, he had his brown hair cut in a neat “short back and sides.”

Health and safety in the workplace was never high on the list of priorities during these early years. Certainly, it was not unusual for children to have access to the buildings around the Malin factory. On 6 July 1907, several local kids, including Les’ youngest sister, Dorothy, were skylarking in the factory yard. Mary Malin had attached a rope to a beam in the shed for straining jelly. One boy, John Clark (who lived in Holmes Street) was walking on stilts in the when he decided to show off, declaring, “Watch me hang myself.” After tying a hitch knot in the rope, he placed the loop over his head, but didn’t allow for the stilts giving way. With the knot jammed, the boy hung suspended in the air, ‘his tongue lolled out of his mouth.’ The other children thought this was part of the joke, but became terrified ‘as his eyes began to protrude from his head and his face turned black’ and all ran away. Except for Dorothy, who ran for her mother, who cut the poor boy down. It took several hours for young Clark to regain consciousness. By the following day he was pronounced out of danger, ‘though still suffering from the effects of his foolhardiness.’

When it was announced on 3 April 1909, that Les was engaged to Eva Josephine Rogerson, it seemed that the Malin family was set to enjoy happier times. Eva was the eldest daughter of local police detective, Joseph Rogerson. The family was well-known and liked – Joseph Rogerson had been a talented cricketer in his youth, twice playing agains visiting English teams. At a time when reciting was considered a huge accomplishment, Eva was a popular performer at local concerts and competed successfully at Royal South Street and other eisteddfods. She was charming and confident and Les adored her.

Their marriage took place at the Neil Street Methodist Church (where both families worhipped) on 9 June. It was a ‘very pretty wedding’ with Eva dressed in a directoire gown of ivory chiffon glacé – seemingly the height of fashion and the scandal of puritans worldwide. It was trimmed with applique and tassels and she carried a shower bouquet that was a gift from Les.

The service was performed by Reverend Samuel Cuthbert, who was the incumbent minister at Neil Street. His church had been decorated by Eva’s friends with arches of ferns and white chrysanthemums.

Eva had three bridesmaids – Misses L. Matthews, and Miss L. Harrison, and Les’ sister, Lavinia. They were dressed in gowns of crème serge silk or cashmere, with silk and edelweis lace trimmings, appliques and tassels. Miss Harrison wore a hat of magenta panne velvet and this colour was also picked out in the streamers attached to their bouquets. The all wore gold and pearl crescents that were gifts from Les.

To complete the bridal party, Les chose his eldest brother, Frank, as his best man; George Clark and James Laughlin were his groomsmen.

The wedding breakfast was held in the Sunday School hall.

Les and Eva also exchanged gifts – the bride was given a set of black fox furs, the groom received a travelling bag and a gold tie-pin. Their guests showered them with a delightful array of gifts, with an inordinate amount of silverware.

The list was long and gives a wonderful insight into the era…some may even recognise a family name.

‘…Mr J. Rogersen piano, and figured clock and vases; Mrs J. Rogerson, house linen; Mrs J. W. Malin, cheque, hymn book and Bible; Mrs J. W. Malin and family, eiderdown quilt; Mrs R. Hamilton, silver jardiniere, pot and fern; Mr and Mrs T. Robinson, silver and blue cake-basket; Air and Mrs Barnard, Beeac, silver serviette rings; Mr and Mrs Morrish, Bullarook, silver and green jam-dish and spoon; Mr and Mrs Kinred, N.S.W. silver toast rack; Mr and Mrs J. Matthews, silver and cut-glass biscuit barrel; Mr and Mrs Von Mylius, Melbourne, cheque; Mr and Mrs Cantilon, Melbourne, silver bread board and knife; Miss V. Gates, porcelaine jardiniere; Miss E. Harrison, silver jam spoon, butter knife, and bread fork; Miss G. Wilson, set silver tea spoons; Mr and Mrs McGibbbon, Melbourne, porcelaine salad bowl; Miss M. Rogerson, fruit dish; Mr D. Cameron, Melbourne, afternoon tea spoons; Mr W. Rogerson, sideboard; Mr A. Wallace, Melbourne, set carvers; Miss Kennerwell, Echuca, silver-bread fork; Miss N. Smith, silver sugar scoop; Miss M. Hill, Melbourne, copper hot-water kettle; Mr H. Berryman, Melbourne, handsome dinner set in dark blue and gold; Mr A. Rogerson, cheque and marble clock; Mr F. Vanderslings, Melbourne, silver pickle jar; Miss A. Cameron, Melbourne, point lace d'oyley; Miss D. Malin, fancy work; Mr F. Woodward, pair hall curtains; Miss K. Roberts, gold horse-shoe (ornament); Mrs Malin, sen., silver cruet; Masters H. and B. Rogerson, kitchen utensils; Miss G. Leckie, antimony card tray; Mr Gunst (Melbourne) and Miss Matthews, silver teapot; Mr and Miss Meldrum, silver salt dishes; Mr T. Bevan, cheque; Messrs A. Laurence and Co, Melbourne, perfume; Miss E. Dean, New Zealand, Maltese lace; Miss P. Grainger, silver butter knife and jam spoon; Miss L. Harrison and, Mr J. Laughlin, pair bronze vases; Miss J. Leckie, antimony photo frame; Mrs Middleton, hand painted table cover; Miss. V. Malin, N.S.W.; fancy work; Mr and Mrs Uren, fruit dish; Mr G. Clark, silver jam dish; Miss E. Grainger, silver candlestick; Mr and Mrs R. Berryman, silver pickle jar; Mr and Mrs E. G. Adams, N.S.W. silver serviette rings; Mr and Mrs G. Bevan, Beeac, silver egg cruet; Mr and Mrs E. Adams, N.S.W., silver toilette tray; Mr and Mrs . J. Hill. Echuca, ruby vases…’

That evening the couple left by train to begin their honeymoon. Eva was dressed in a navy blue tailor-made outfit with a hat of Wedgewood blue glacé. The guests spent the remainder of the evening being entertained by Mary Malin at the family home in Holmes Street.

On returning to Ballarat, Les and Eva moved into their first home together, at 421 Drummond Street north. They filled with their home with all their lovely wedding gifts and began adding their own happy memories. Within just a few weeks, Eva realised that she was pregnant.

Life was perfect.

On the 10 April 1910, Eva gave birth to a fine baby boy, who they named Lloyd Vivian. Before the day was over, despite the attendance of two doctors, Eva was dead.

The community read of the joy and tragedy in the saddest dual announcements in the local newspaper.

BIRTHS

MALIN – To Mr and Mrs L. J. Malin,

421 Drummond Street north, on 10th

April – a son.

DEATHS.

MALIN – On 10th April, at 421 Drummond

Street north. Eva Josephine (nee

Rogerson), dearly-beloved wife of Leslie

John Malin.

The funeral took place two days later. Four policemen carried Eva’s coffin from the house before the large cortege made its way to the New Cemetery. Reverend George Netherway had the sad task of burying the young wife and mother.

Heartbroken, Les immediately sold their home in Drummond Street. He sold everything, including the piano that had been a wedding gift from his father-in-law and their Edison phonograph with its extensive collection of records that he and Eva had so enjoyed listening to. He moved back to Holmes Street, where he threw himself into the business alongside his mother. Lavinia, who was still living at home, took over the full care of baby Lloyd.

In 1912, Les became briefly involved with a younger woman, Edith May Thomas. The girl fell pregnant, but it was clear that Les did not intend their relationship to go beyond a dalliance. When the baby boy, named Leslie William Thomas, was born on 7 December 1912, Les ‘did the best he could for mother & boy by making provision in a lump sum.’ Although ex-nuptial children were common, the father taking responsibility was quite rare. Clearly, he believed the issue was settled.

By 1914, Malin’s sauce was amongst the top products of its kind in Victoria – shops stocked the three most popular brands with Malins able to undercut their rivals. White Crow and Rosella were selling the tomato sauce for 6-shillings a bottle, whilst Malins could be purchased for 4½-shillings or a large bottle for 8½-shillings.

Despite the ongoing success, by July of that year a decision had been made to sell the residence and factory in Holmes Street. Mary Malin was approaching 60 and it was seen as a good time to divest themselves of the business. Initially offered at auction in July, before a second sale in August, it was promoted as prime real estate within close proximity to the railway workshops being constructed off Lydiard Street, with the suggestion that it could be ‘purchased for an up-to-date boarding house for working men’ or ‘most splendidly adapted for extensive factory, residential, or club purposes.’

However, the outbreak of war changed everything, and when the auction failed to attract a suitable buyer, the Malin family continued to operate their factory.

At key points throughout the war enlistment drives were used to influence would-be volunteers. In the months immediately following the Landing at Gallipoli numbers surged. There was a subsequent ‘enlisting boom’ after the dramatic evacuation of the Peninsula.

On 14 February, Les Malin presented himself at the Ballarat Ranger Barracks to begin the process of enlisting in the AIF. Doctor Archibald Brown Campbell (then acting as a major with the Army Medical Corps) dealt with Les’ physical examination and found him to be in excellent shape. At 34, Les easily met the requirements in height and chest measurement. Dr Campbell noted that Les had been vaccinated, but that he was considerably myopic in his right eye.

Although he had no previous military training, Les was an excellent recruit in all other aspects. It was announced in the newspaper the next day that he was one of the latest volunteers and that he would enter camp ‘as soon as he can free himself from business responsibilities.’ This proved more time consuming than Les had hoped and it wasn’t until 7 June that he took his oath of service.

After being in camp at Ballarat for just over two weeks, Les received his unit posting and joined E Company of the 3rd reinforcements of the 39th Infantry Battalion with the regimental number of 2109.

As a parent, Les also needed to make special arrangements for Lloyd’s ongoing care: to cover all bases, he named his mother as legal next-of-kin and his sister, Lavinia, as Lloyd’s guardian.

When he left for the Front, Les was confident that he had put everything in place. He embarked from Melbourne on 25 September onboard HMAT Shropshire. On 28 September, as the Shropshire sailed through the Great Australian Bight, Les slipped a detailed message into a bottle and threw it into the water.

'Should this reach you, it will be of interest to learn that the 3/39th are, up to date, doing particularly well. We are on board the ________, and make a total of 1700 troops in all, besides officers and crew.

You would look aghast if you were to see F. Vaughan, G. McHarg, P. Sevior, J. McLennon, F. Phelan, E. Morrison, Les Malin, F. Packham, L. Hill, G. Flockhart, H. Walker, R. Trengove, A. Shaw, J. Hastie, and many other old Ballarat boys I could recall scrambling for their food at messtime. Really you would never dream that they had had other than a backyard education. However, that is all in the game, and none of our friends in the Golden City will blush at the picture presented.

We are absolutely lost for any news of the outside world, and it rather damps our spirits to think of going another 30 days before seeing civilisation.

Both Mr [George] Hay (q.v.) and Mr Christensen are well…'

(The letter was found on the 29th April 1917 by Mr Hugh Marr of Hopetoun, Western Australia and forwarded to The Courier office).

The Shropshire continued its voyage via South Africa and were at sea nearly seven weeks, before reaching Plymouth on 11 November.

Les was soon settled in camp at Hurdcott on the Salisbury Plain. For this initial period, he was stationed at the No11 Camp and posted to the 10th Training Battalion. In his first letter home he was able to detail some of their activities.

‘…Hurdcott Camp, England, November 23rd, 1916.

We have got to our business camp at last. I can't tell you exactly where it is, but it is a connection of the Salisbury group of camps. We arrived here on Tuesday afternoon, and all the rest of that day was taken up with the apportioning of huts, issuing of blankets, and getting tea.

The next morning we were up at 6.30, and had a real gruelling at physical jerks, squad drill in the morning, and squad drill and practice with the gas helmet in the early afternoon, and at 3:15 pm we were lined up for our fourth inoculation for anti-typhoid, which consisted of the injection into the left arm of 1000 milligrams of germs. This inoculation plays up generally with the fellows to such an extent that they always give them 48 hours leave, in which time we are supposed to take it quietly. However, this morning I am feeling very little effects in the arm itself, but the whole system seems to be affected, with the result that none of us feel like work.

The gas helmets above referred to consist of a cloth bag, which goes right over the head and neck, leaving enough cloth hanging to allow the open part to be tucked inside the neck of the tunic. Two glasses are fitted in front in a position bringing them level with the eyes, and a mouth tube also is attached at a point opposite the mouth. The mouthpieces we take in our mouths, and at the end on the outside is a rubber valve, which allows the air to be emitted, but not to be admitted. The whole cloth is soaked in some

chemical combination, and as the gas-laden air filters through the cloth covering, these chemicals so act on the gas as to destroy the poisonous effects of the gas. This style of helmet is now no longer in active use, as an improvement has been effected, the chemicals in these new ones being contained in a cylinder which is attached to your belt, and at the bottom of this cylinder are perforations through which the air passes, and thus coming in contact with the chemicals as it passes to the nose becomes purified.

You would have laughed to see our squad covered with there old helmets and doubling about the parade ground. They looked like so many divers, with headgear only on.

The first day we came here I saw Sonner Lyons (q.v.). He is looking real fit, and has just completed a six months' furlough after his wound in the hip, and is going back to France the end of this week. The next day I ran into Ted Reid, of the Victoria Bank. He has not been to the front, being prohibited by a bad knee, which he still has bandaged. He is now fatiguing in the butcher's shop, and it looked funny to see him wheeling away a barrow load of shin bones.

His brother Len is in France, four miles behind the firing line in the Q.M.'s office, so he is pretty safe. Ted

asked after you, and desires to be remembered to all.

They all tell us it is no fun at the front, but, of course, we didn't enlist for a holiday.

How are you all getting on? I had my first letter from home yesterday, and I assure you it put great heart into me. I am, however, living in hopes that the next mail will be kinder to me. Christmas and New Year will have come and gone er this reaches you, and I trust you will all have spent a happy time.

The 39th Battalion are not yet at the front, but are due to go any time. They have absorbed most of the 1st and 2nd reinforcements, and our officer told us last night that they wanted about 100 from our company. I have not heard enough particulars yet to say whether I'll volunteer or not, but it is possible I may…’

Les’ posting to the 10th Training Battalion was made permanent in early 1917, and on 25 January he was promoted to the rank of corporal with the added benefits of “extra duty pay.” His work with the training battalion involved him developing an extended knowledge of chemical warfare, some of which he conveyed in a letter to his mother. Understandably, the presence of poison gas could cause panic amongst the troops and it became necessary to educate the men and attempt to instil confidence in the updated gasmasks. However, for many of the soldiers “gassed” on the Western Front death was a slow process, often coming years after statistics for the Great War had ceased to be collated.

'…It is unnecessary to tell you that the use of gas is against the constitution of The Hague Convention; but that, like the piece of paper, has been waived by the Germans, who have and will continue to use poisonous gases as a means to the destruction of their enemies. Not only are the British depending on their protective devices, but they are treating the enemy to a little of his own in return when opportunity presents itself.

There are three kinds of gas generally used by the Germans, viz, chlorine, phosgene, and tear-producing. Chlorine is a poisonous gas, and is mostly used. It attacks the mucous membranes of the throat and lungs, quickens the pulse, and produces a choking sensation, rendering the victim unable to take in fresh air, thus choking him to death.

Phosgene is even a worse gas than chlorine, because it is not easily detected, and it is possible for a soldier to be affected unknown to himself at the time. It affects the nerves, and is slow in its working, so that days after a soldier has been attacked by the phosgene gas his nerves break down, and only in this way does he know that he has been the victim of phosgene gas.

The tear producing gas causes copious weeping of the victim, rendering him temporarily useless, as he cannot see, and therefore falls an easy victim to the enemy's bayonet.

Chlorine gas is most to be feared, as its effects may be instantly fatal, whereas with the other two gases the victim may in the case of phosgene soon recover, and in that of tear-producing gas he will soon recover, the effects lasting only for a few minutes.

I had the pleasure (in the course of my instruction) of passing over 400 men through gas today ten times stronger than what they will ever meet at the Front, and not in any instance were the men inconvenienced. These 400 men are full-trained soldiers from all the companies in the 10th Training Battalion, and tomorrow they are being sent to France to take their places in the trenches, and I am proud I had the honour of assisting to teach them.

There are four of us gas specialists, and the work is of a deeply interesting character, including an occasional lecture on 'Anti-Gas,' which I had the honour of delivering before 100 men yesterday.

The plain on which we are camped is the biggest run of plain country in England. It is 25 miles in width, mainly moor land, and being comparatively flat and unprotected by hills and trees, it is very bleak. The frosts are very severe at night…'

Like many of his compatriots, Les had the opportunity of spending time in London. He, however, chose to record images that the ordinary digger might have overlooked. In letters to his mother, Les displayed an individualistic writing style. Mary obviously enjoyed his vivid and colourful way with words, but Les was aware that these letters would be of particular interest to his young son Lloyd, who was soon to celebrate his seventh birthday.

'…I was looking for that famous institution, the Bank of England, and was leaning against its wall, when I stopped a policeman and asked him where the Bank of England was. The policeman looked at me, and when he saw I was serious he smiled and said, 'Why, you're leaning up against it.' I said, 'What, this old forlorn building?' And it looked outwardly for all the world what you would imagine a foundry premises to look like, after years of smoke and grime pelting on it. It was different from the other buildings we saw because of the plainness and simpleness of its outward appearance. But this applies solely to the exterior, for when you come to get inside, the solid, plain, richness of the place is very unmistakable.

The first thing to strike one at St Paul's Cathedral is the number of pigeons on the front steps and on the footpaths around the Cathedral. These birds live in the cornices of the buildings around, and it is a custom for the people to feed them daily, and apparently this has been going on for so long that the birds look upon it as their right, and they get quite accustomed to the procedure. The birds are very quiet, and if you have food they will get on your hat, shoulders, arms, or anywhere at all. The most striking sight I saw of their domesticity was two on a boy's chest, picking grains of wheat from his open mouth.

The Tower of London, St Paul's Cathedral, and Westminster Abbey represent three distinct styles of architecture, viz, Norman, Italian and Gothic. As soon as you enter the building you are reduced at once to a sense of solemnity by the fact that you are treading on the stones covering the graves of most eminent men and women…

[Describing his first aeroplane flight]…It was a nice sensation of sliding through space. First above fences and then to see tall trees pass under us; then up and up till trees looked like grass and men like fly-specks. It was a beautiful sight to see the little creeks running into the river like different sizes in silver ribbons, all set off by the glorious richness of the grass around.

On Monday we had a 17-mile march, with full pack and rifle. It was a hard march, at the conclusion of which Jim Darling and I made straight for the YMCA, where we had a good warm up and a couple of cups of hot tea. The weather here is terribly cold. Today we were out on the range from 11am. It snowed pretty well all the time, so much so that at 1 o'clock we had to give up and come home…'

'What a gruesome sight and feeling it gave me to see this wonderful City of London in semi-darkness! All the street lamps were shaded, and had the lights directed to the ground immediately underneath the lamps; all the buses, motors, and, in fact, all lights were correspondingly subdued; even in the trains orders were posted up to the effect that all window-blinds must be drawn when out of stations. Of course, the reason is obvious.

My first day in London I stayed at a place called the War Chest. It is right opposite the Australian Headquarters. I think it derives its name from the fact that it is run by the AIF, and the profits, if any, go to the war chest. As a matter of fact so cheap is the fare they give you, and so good in quality, that they do not clear expenses, but on account of it being such a boon to the soldiers they keep it going. Previous to being taken up by the AIF it was run by the YMCA, and they lost £560 in the last half-year, so they turned it up. You can get bacon and egg, sausage and egg, or bacon and sausage, followed by a choice of three puddings, bread and butter ad lib, and two cups of tea or coffee for 1/. The same meal would cost 2/6 at a restaurant. Hot shower baths are free, and there is every convenience.

After a comfortable night's rest four drag-loads started out sight-seeing in the morning. For the tour we paid 4/, which covered all expenses for the day: each drag having a guide, who explained all the interesting features on our tour of sight-seeing.

During the drive we saw the biggest dwelling house in London, the tallest dwelling house, and the smallest dwelling house. The tallest is Queen Ann's Chambers, 14 storeys high; the biggest, Buckingham Palace, the King's residence; and the smallest place is opposite Hyde Park, being a two-storey house built in between the walls of two terraces, whose walls are 4½ feet apart, and this small house is therefore 4 feet wide, but extends a good way back, and would be a suitable residence for the proverbial Tom Thumb and family.

Hyde Park is a sight to remember. The ladies mostly adopt the straddle style, though some used the side-saddle. The liveried coaches looked well, and nearly every lady would wave her handkerchief to us, especially the elderly ladies…'

Finally, on 1 October, Les was released from his duty with the 10th Training Battalion and the next day he sailed from Folkestone for France.

After being processed through the 3rd Australian Divisional Base Depot at Rouelles, Les marched out to join his unit on 6 October. When he reached the 39th Battalion four days later, the men were detailed on work parties preparing tracks at Hussar Farm, south of the village of Potijze. They had just come out of the line having taken part in the successful advances at Broodseinde on 4 October.

On the night of 11-12 October, Les had his first experience of action on the Western Front – this included the enemy shelling the 39th Battalion with gas and high explosives as they approached Beecham Farm in the Passchendaele sector. Due to a strong wind and soft ground, ‘the gas had no effect,’ and they reached their assembly point with few casualties.

As they moved forward the enemy maintained a heavy artillery fire. The loss of officers caused confusion, with the men bunching up, unsure how to proceed. The forward troops were also held up by machine-gunners and snipers.

This was a harsh initiation for Les Malin. Although relief began at 7pm on 13 October, the return journey was incredibly difficult. The track was badly damaged by shellfire and heavily water-logged. ‘Through the Operations the weather was very cold and wet and severely taxed the strength of the men.’ It took three and a half hours to reach safety.

Les was still in the front line on 26 November when he began to suffer severe stomach pains. After reporting sick, he was admitted to the 9th Australian Field Ambulance before being transferred to the 53rd (1/1st North Midlands) Casualty Clearing Station, which was then housed in the asylum at Bailleul. There it was confirmed that Les was suffering from appendicitis. He was then transferred by the 36th Ambulance Train to Calais, where he was admitted to the 35th General Hospital on 2 December. A further delay of five days before he was evacuated to England appears to indicate that the attack was not acute. He left Calais onboard the Hospital Ship Brighton on 7 December and was admitted to the Southall Auxiliary Military Hospital (affiliated to the Edmonton Military Hospital) in London, later the same day.

Surgery for appendicitis was not undertaken lightly, as this was still deemed a dangerous procedure. However, it was considered necessary in Les’ case and the operation was performed on Christmas Eve. During his time at Southall, Les was largely cared for by members of the Voluntary Aid Detachment who staffed the hospital.

On 5 February 1918, Les was transferred across to the 2nd Australian Auxiliary Hospital in nearby South Road. A week later, he was fit enough to be discharged to furlough. This allowed him two full weeks to relax before he was to report for duty at the No1 Command Depot at Sutton Veny.

Les was still only fit for light duties (classified B1a3), but the authorities made good use of this continued recovery period. His eyes were examined and new glasses were ordered. The dentist also supplied him with partial upper and lower dentures.

By 16 April, Les was ready to resume full duty and he left for the Overseas Training Brigade at Longbridge-Deverill. On 8 May, he arrived at the Canadian Intermediate Base Depot on the outskirts of Étaples. He rejoined his unit two days later.

This had been a prolonged period of action for the men – they had just come out of the line at Mericourt-l’Abbe, after having been rushed to the Somme during April to take part in halting the German advance on Amiens.

The 39th spent June in the sectors of Blangy-Tronville and Mont du Boix de l’Abbe – a wood at the rear of Villers-Bretonneux, which had been the furthest limit of the German Offensive on the town.

All Australian units were elated by the success of General John Monash’s plan for the Battle of Hamel on 4 July. In just 93-minutes the Australians (assisted by American troops, ‘who acquitted themselves well’), proved the benefits of careful planning, psychology, and the proper use of advance weaponry, including tanks and aircraft. It was a textbook example of modern warfare.

The remainder of the month saw an increase in activity on both sides of the line, with the 39th spending much of their time in the vicinity of Vaire Wood.

On 8 August, the Allies launched a mass attack aimed at pushing through the German frontlines. When the attack opened at 4:20am, the 39th Battalion was held in a support position. The Battle of Amiens had begun.

‘Everything in the attack went to time table, the misty morning assisted by artificial fog helped the infantry altho. hampered the tanks to a certain extent.’

Around 10am they received orders to move to the enemy trench system. They were able rest and ‘remained tactically disposed.’ Two platoons from the 39th moved forward with the 42nd Battalion and were able to capture 40 of the enemy without suffering any casualties. The men then settled into billets at Hazel Wood.

Two days later the 39th was deployed in what proved to be a poorly planned attempt to capture the village of Proyart. The troops became blocked near the hospital, and before they could move, they were attacked by enemy aircraft, suffering multiple casualties.

On 30 August, the battalion moved from Curlu to the vicinity of the Hem-Monacu Railway Station. Their attack plan led them along a big gully east of Bray.

Shelling caused a number of casualties late in the day. In one explosion, Les Malin was hit by multiple pieces of shrapnel. He was evacuated to the 9th Australian Field Ambulance for immediate care before being transferred to the 61st (2/1st South Midland) Casualty Clearing Station at Veqcuemont. There he was found to be suffering from wounds to his head, face, left shoulder, right arm, left leg and both feet. Despite the damage, Les held on through the following day. However, it was clear that he was too ill to be moved. Although the information was not recorded, it is possible that he developed gas-gangrene, which could spread rapidly leading to death. On 1 September 1918, Les Malin succumbed to his wounds. Chaplain H. Jones, who was attached to the 61st CCS, buried Les’ body in the extension to the Daours Communal Cemetery, 2¾-miles west of Corbie.

The Reverend Joseph Snell, superintendent of the Ballarat West Methodist Circuit, and one of the most highly regarded ministers in Ballarat, was given the sad task of informing Les Malin’s mother of her son’s death. The news was conveyed on Friday night, 13 September.

Sundays in Ballarat had become a sad mirror on the war, one that reflected the communal suffering as young local men were honoured for their sacrifice. Such long lists of names killed in battle would no longer be tolerated, but even war weariness of 1918 did not prevent the ongoing ceremony. So, on 22 September, the flags on the Town and City Halls were lowered once again to half-mast.

Those whose names added to the roll that week were Percy Towl, John Bryan Cuthbert, Victor Jolly, Arch Peady, Bill Kisler, Charlie Goddard, Sep Fishwick, George Welsh, George Frampton and Les Malin.

Bill Kisler and George Frampton were also members of Ballarat’s 39th Battalion.

This was a particular difficult time for Mary Malin. Edith Thomas had seemingly reinserted herself into the situation after Les had left for England. Although Edith was now married and had three further children, Mary had been informed that, after hearing of Les’ death, she intended to claim his belongings ‘on behalf of her child.’ On hearing this, Mary had become understandably distressed. She sought help from a Mr F. Harris, from Ballarat, a member of the Sailors’ and Soldiers’ Fathers Association who communicated with Base Records on her behalf. Harris was at pains to point out ‘…the deceased’s mother is a splendid type of woman, for whom I can personally speak in confident terms and I feel sorry for her in her trouble…’

It seems there was never any intention by the Defence Department of giving precedence to a claim from outside the immediate family. They did, however, acknowledge Edith’s claim by providing her young son with a pension; he was awarded seven shillings and sixpence a week. Mary Malin was also recognised as being dependent on her son and received a partial pension, whilst Lloyd initially received 12 shillings and sixpence for his support. Concern over medals owed to Les were alleviated when the British War Medal and Victory Medal were given to young Lloyd.

It was Les’ intention that his mother manage his affairs and indicated this by making her his sole beneficiary in his paybook Will, dated 17 March 1917. Mary also received a letter from a Mrs Elliott (believed to be Jane Elliott), of Rotherstone, Devizes in Wiltshire, that Les had left ‘a small tin trunk’ with her prior to embarking for France. The trunk supposedly contained a lot of ‘civilian clothes laid by’ for his use after the war. This matter was dealt with by AIF Headquarters in London, but Mary was disappointed by the returned items, which appeared to be ‘of limited value.’ The parcel from Mrs Elliot contained a book, cards, a pouch, an aluminium cup, a Jack knife, two pairs of socks and a pair of mittens.

When Les’ effects were returned from the field, the two packages held the most personal items that he had carried with him daily – a cigarette case, his shaving brush, a rule (which had been broken), metal mirror, wallet, photos, letters, cards, three coins, his identity disc, a note book, purse, a writing pad, dictionary, and his hair brush. A sum of 40 Francs had been passed to the Chief Paymaster to be exchanged and added into monies owed to Les on account of his service. There was also Les’ diary which he had kept during his time on the Western Front. It captured the ready intellect of its writer, and was filled with his own personal observations, often coloured by his particular sense of humour. His pragmatic nature appeared to shine through, 'never allowing him to look back' on what might have been.

For the inscription on Les’ grave, Mary Malin chose from the heart.

“In Memory of a Good Son. Loved By All.”

In early 1920, Mary, Lavinia and Lloyd moved to 312 Eyre Street, on the corner of Raglan Street, which is still one of Ballarat’s most notable homes. Although Mary appeared to be ‘in the best of health,’ she suddenly fell severely ill and died on 6 June 1922.

After her mother’s death, Lavinia and Lloyd left Ballarat, living for a brief time in Point Nepean Road, Cheltenham.

In the 1920’s, Lloyd joined the Education Department. Early placements for young teachers took them all over the State, and this was no different for Lloyd. This meant long periods of separation from his doting aunt, Lavinia. Having devoted her life to his care, it was not surprising that she would now look to her own future. In 1929, Lavinia, who was then 46, married George Herbert Harris and settled into married life.

Lloyd was transferred to Lake Bolac in the early 1930’s. There he met Christina Wills, daughter of local grazier, Lewis Whiteway Wills. They were married in 1935, and began their married life at the Lower Delegate River School in Gippsland.

During the Second World War, the Malin family suffered another tragic loss. Les’ nephew, Corporal Ian William Lyell Malin, (NX1103 Headquarters Base Area Middle East) died in Egypt on 11 August 1941 from an intestinal obstruction following a bout of appendicitis. He was the only son of Les’ brother, Frank. There was an eery similarity to his uncle’s illness over twenty years earlier…

In September 1941, Lloyd resigned his position as a teacher at the Wagga Wagga High School and he and Ena returned to Lake Bolac.

The subdivision of the Lake Boloke Station in 1903 allowed the Wills family to purchase the northern section of the property. They named the new farm “Fintry” after the Scottish birthplace of Ena’s maternal grandmother. Lloyd and Ina took up land on the south-eastern shore of Lake Bolac, calling their property “Brolga.” They devoted themselves to building the farm and to raising their two children, Lesley and John.

When Latvian refugee, Augusts Gaspuitis arrived in Lake Bolac in 1947, it brought home the realities of war in Europe. The young man had lived through German occupation and survived forced deportation to Germany in September 1944. Augie soon found a new home at Brolga, where he became such an important member of the family he was sometimes referred to as “Augie Malin.” He remained at Brolga until his death on 18 May 1983.

John Malin continued running of the property after his mother’s death on 23 July 1980. Lloyd later returned to Ballarat, where he died at the St John of God Hospital on 12 September 1988.

The circle was now complete.