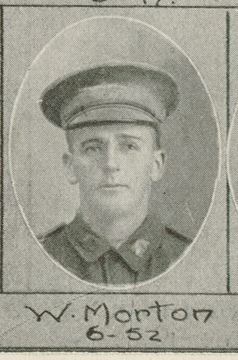

MORTON, William

| Service Number: | 2700 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | 6 May 1916 |

| Last Rank: | Private |

| Last Unit: | 52nd Infantry Battalion |

| Born: | Leicester, England, date not yet discovered |

| Home Town: | Wamuran, Moreton Bay, Queensland |

| Schooling: | Not yet discovered |

| Occupation: | Farmer |

| Died: | Killed in Action, Dernacourt, France, 5 April 1918, age not yet discovered |

| Cemetery: |

No known grave - "Known Unto God" Villers-Bretonneux Memorial, Villers-Bretonneux, Picardie, France |

| Memorials: | Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour, Caboolture District WW1 Roll of Honour, Caboolture War Memorial, Villers-Bretonneux Memorial |

World War 1 Service

| 6 May 1916: | Enlisted AIF WW1, Private, 2700, 52nd Infantry Battalion | |

|---|---|---|

| 7 Oct 1916: | Involvement Private, 2700, 52nd Infantry Battalion, --- :embarkation_roll: roll_number: '19' embarkation_place: Sydney embarkation_ship: HMAT Ceramic embarkation_ship_number: A40 public_note: '' | |

| 7 Oct 1916: | Embarked Private, 2700, 52nd Infantry Battalion, HMAT Ceramic, Sydney |

Help us honour William Morton's service by contributing information, stories, and images so that they can be preserved for future generations.

Add my storyBiography contributed by Ian Lang

MORTON William #2700 52nd Battalion

Will Morton was born in Leicester and emigrated to Australia at the age of seven. By the time he enlisted on 6th May 1916, Will stated he was 29 years old, a single farmer from Wamuran on the Kilcoy line.

After a period of training at Enoggera Will was allocated as part of the 6th reinforcements for the 52ndBattalion. He embarked on the “Ceramic” in Sydney on 7th October and arrived in Plymouth on 21stNovember 1916.

Less than a month after arriving in England, Will was posted to his battalion which he joined on 2nd January 1917. The winter of 1916/17 was the harshest experienced in France in almost 40 years. Many of the Australians manning the trenches suffered terribly from frostbite, trench foot, lice and scabies. In addition, exposure to below freezing conditions brought on serious chest complaints and influenza.

Will spent most of 1917 in and out of various hospitals and field ambulance stations with a number of complaints. In the beginning of 1918, Will was granted three weeks leave in England. He may have used this time to meet up with members of his family he had not seen for over 20 years.

Will’s return from leave coincided with the start of Operation Michael, the German spring offensive that Ludendorff hoped would win him the war. In response, Haig ordered the 3rd and 4th Australian Divisions to be rushed south. The first units to be mobilized were battalions of the 12th and 13th Brigades; which included the 52nd Battalion. The battalion boarded buses and trucks for the journey south on 25th March but only got about half way to their destination before orders were changed and they spent 24 hours awaiting new orders.

The 12th and 13th brigades were ordered to make their way to Dernacourt, a small village on the railway line between Amiens and Albert. This deployment required a forced march of almost 30 kilometres through the night with the entire German army somewhere out on the left. There were reports that German armoured cars were on the roads but the cars proved to be French farm machinery.

Upon arrival at the assigned position, the two brigades were ordered to take up positions on a ridge facing the gathering Germans on the other side of the railway line. There were no trenches and the men had to dig shallow pits while under enemy artillery fire. Over the next four days, the men of the 12th and 13th Brigades established a forward defensive line on the railway embankment. The enemy were only a few hundred metres away, massing in large numbers for an attack. Almost opposite the village of Dernacourt was a railway underpass which had been chosen as the boundary between the two brigades with the 12th on the left of the underpass and the 13th on the right.

A massive attack by up to three German divisions began at dawn on 5th April. The underpass proved to be the weak link in the defensive line and the German storm troops were able to pour through and quickly outflank the troops on either side. Witnesses stated that it was then that Will received a burst of machine gun fire to the head, killing him instantly. The survivors of his section were practically surrounded and had to withdraw under fire, leaving their dead and wounded behind.

As it happened, there was another Caboolture man in the 52nd there on the embankment that day; Lieutenant Leonard Boase. Boase would be nominated for a VC for his actions that day. Boase was severely wounded and taken prisoner. He was ultimately awarded a DSO probably on the basis that you could not award a VC to a man who was a POW!

Counter attacks later in the day by other battalions of the two brigades finally thwarted the attack but it had been a close run thing. Large numbers of men were taken prisoner, killed or missing. It would not be until the German advance was finally turned in August of 1918 that investigations could be held into what had happened at Dernacourt.

No trace of Will’s remains were located when the Australians could finally search the battlefield. The circumstances of his death also meant that there were no personal possessions to return to his mother. William Morton was one of the almost 11,000 Australians who gave their lives in France and have no known grave. Memorials to the missing were constructed by the British at Ypres and Tyne Cot in Belgium; and at Theipval in France. The Australian Government were slow to dedicate the Australian National Memorial at Villers Brettonneux; which was finally dedicated by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in 1938 (just in time for WWII). Will Morton is listed on the limestone tablets that make up the three walls of the memorial.