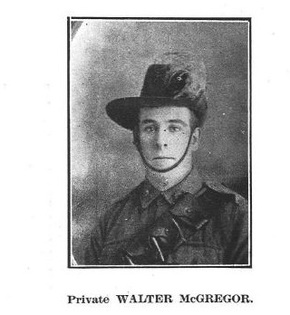

MCGREGOR, Walter

| Service Number: | 3708 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | 27 April 1917 |

| Last Rank: | Private |

| Last Unit: | 47th Infantry Battalion |

| Born: | Yalangur, Queensland, Australia , date not yet discovered |

| Home Town: | Meringandan, Toowoomba, Queensland |

| Schooling: | Gowrie Little Plains, Queensland, Australia |

| Occupation: | Farmer |

| Died: | Killed in Action, Dernacourt, France, 5 April 1918, age not yet discovered |

| Cemetery: |

No known grave - "Known Unto God" Villers-Bretonneux Memorial, Villers-Bretonneux, Picardie, France |

| Memorials: | Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour, Goombungee War Memorial, Toowoomba Roll of Honour WW1, Toowoomba War Memorial (Mothers' Memorial), Villers-Bretonneux Memorial |

World War 1 Service

| 27 Apr 1917: | Enlisted AIF WW1, Private, 3708, 47th Infantry Battalion | |

|---|---|---|

| 2 Aug 1917: | Involvement Private, 3708, 47th Infantry Battalion, --- :embarkation_roll: roll_number: '19' embarkation_place: Sydney embarkation_ship: HMAT Miltiades embarkation_ship_number: A28 public_note: '' | |

| 2 Aug 1917: | Embarked Private, 3708, 47th Infantry Battalion, HMAT Miltiades, Sydney |

Help us honour Walter McGregor's service by contributing information, stories, and images so that they can be preserved for future generations.

Add my storyBiography contributed by Ian Lang

# 3708 McGREGOR Walter (Mac) 47th Battalion

Walter McGregor was born at Gowrie Little Plains near Meringandan outside Toowoomba to John and Agnes McGregor. He attended Gowrie Little Plains School and then worked on the family farm. Walter attended the Darling Downs Recruiting Depot on 27th April 1917. He stated his age as 25 and occupation as farmer. Walter’s brother George had enlisted in the Light Horse in January 1915 and it is likely that Walter remained at home to assist on the farm while his brother was away. The serious state of enlistments in late 1916 and early 1917; exacerbated by the failure of the conscription plebiscite, may have placed pressure on families such as Walter’s to step up and meet the desperate need for reinforcements in the AIF.

Walter, travelled to Enoggera and was placed in a depot battalion for initial training. He was granted a period of home leave the first week in July and upon his return to camp was allocated to the 10th draft of reinforcements for the 47th Battalion where he appears to have acquired the nickname of Mac. On 2ndAugust 1917, the reinforcements, having travelled by train to Sydney, embarked on the “Miltiades.” The embarkation roll shows that Mac had allocated 3/- of his overseas pay of 5/- to his father. The “Miltiades” followed the usual route for troop ships during this stage of the war, sailing west from southern Australian ports to South Africa, continuing westward into the Atlantic before heading north towards England to avoid encounters with enemy submarines. In the latter half of 1917, the German government had commenced unrestricted submarine warfare on British and American shipping, causing the route followed by the Miltiades to stretch further into the Atlantic sailing around the northern coast of Ireland before entering the Clyde and ultimately Glasgow. The 10th reinforcements landed in Glasgow on 2nd October 1917.

Mac and the rest of his mates took trains south to the 12th Brigade Training Battalion at Codford near Stonehenge in Southern England. Mac spent some time in the group hospital with a case of pneumonia before resuming training. While the reinforcements were in camp at Codford, the five divisions of the AIF were involved in the Flanders campaign in Belgium which would ultimately be bogged down in the mud at Passchendaele. The Flanders campaign would cost the AIF 38,000 casualties and when the surviving brigades were withdrawn from the front, they were in desperate need of a rest. Reinforcements would not be sent until the state of individual battalions had been established.

On 16th January, Mac began his journey to the 47th Battalion. He was marched in on 23rd January where he was placed in “A” Company. The battalion at that time was enjoying a period of rest and recreation in the area around Poperinghe in Belgium. The latter part of 1917 produced a change in the strategic situation as far as the German command was concerned. The Bolshevik Revolution in Russia brought about the end to fighting on the Eastern Front. A peace treaty between Germany and Russia released up to sixty German divisions which, once re-equipped and re-trained, could be used to press home a distinct advantage on the Western Front. The window for exploiting this advantage was however rather small as the entry of the United States into the war and an expected surge in troop numbers from July 1918 onwards would swing the advantage back to the Entente. The German commander, Ludendorff had only a short time to press home his advantage.

The British Commander, General Haig, was fully expecting a German assault in the Spring of 1918 but he guessed incorrectly that the main thrust would be aimed at the Ypres salient in Belgium. When Operation Michael began on 21st March, the main assault was aimed along the line of the Somme River in Northern France, the scene of so much fighting and hard-won victories in 1916.

The British 5th Army, which was holding the line astride the Somme was unable to hold the German onslaught which in some places amounted to a five-times numerical advantage. As the British retreated, often in disarray, the German Stormtroopers retook all of the gains made by the British in the Somme campaign of 1916 and were within a few days of capturing the vital communication city of Amiens. If Amiens fell, Haig might well have lost the war; the situation was deadly serious.

Haig’s response was to order the 3rd and 4th Australian Divisions south to defend Amiens. The first units to be mobilized were battalions of the 12th and 13th Brigades; which included the 47th Battalion. The battalion boarded buses and trucks for the journey south on 25th March but only got about half way to their destination before orders were changed and they spent 24 hours awaiting new orders.

The two brigades were ordered to make their way to Dernacourt, a small village on the railway line between Amiens and Albert. This deployment required a forced march of almost 30 kilometres through the night with the entire German army somewhere out on the left. There were reports that German armoured cars were on the roads but the cars proved to be French farm machinery fleeing the oncoming Boche.

Upon arrival at the assigned position, the two brigades were ordered to take up positions on the exposed forward slope of a ridge facing the gathering Germans on the other side of the railway line in the village of Dernacourt. The coming battle was Mac’s first exposure to extensive enemy attack. There were no trenches and the men had to dig shallow pits while under enemy artillery fire. Over the next four days, the men of the 12th and 13th Brigades established a forward defensive line on the railway embankment. The enemy were only a few hundred metres away, massing in large numbers for an attack. Almost opposite the village of Dernacourt was a railway underpass which had been chosen as the boundary between the two brigades. The four companies of the 47th Battalion occupied the forward positions on the railway line embankment on the left of the underpass with “A” Company and Mac closest to the underpass. On the right of the underpass were three companies of the 52nd Battalion from the 13th Brigade.

A massive attack by more than two full German divisions began at dawn on 5th April. The situation became desperate as German storm troopers poured across the embankment and through the railway underpass. Several machine gun positions which were supposed to be supporting the 47th men on the embankment were eliminated without firing a shot. As the 52nd Battalion on the right began to withdraw to safer positions, the 47th battalion came under heavy fire from three directions, including from the captured machine gun positions in their rear. The 47th Battalion outposts on the embankment and the support lines were shattered. “A” Company had been almost wiped out. The Official History records that the dead and wounded of the 47thlay everywhere underfoot. One of those bodies may have been Mac. There were very few survivors of “A” Company who could accurately describe what had occurred on 5th April and most of those had been taken as prisoners of war. It would not be until POWs were released at the end of the war that the full picture became clear. What was clear that Mac McGregor was amongst those who failed to answer the first battalion roll call.

Mac’s mother received a cable message informing her that her son was listed as wounded and missing, a rather deceptive statement which gave rise to unfounded angst. Agnes wrote to the authorities asking which hospital her son was in and the state of his condition. The reply she received was completely misleading. “The seriousness of the wound is not stated in the cable traffic. In the absence of information to the contrary, favourable progress may be assumed.” This was a standard response to requests of this nature which was clearly false. A court of inquiry conducted into the “Missing” from Dernacourt on 1st November 1918 established that after enquiries with the German POW authorities proved fruitless, Walter McGregor was listed as Killed in Action on 5th April 1918. His body was never recovered.

In 1938, some 20 years after the end of the First World War, the Australian Government constructed the Australian National Memorial at Villers Bretonneux. The memorial was dedicated by the newly crowned King George VI. The memorial records the names of over 10,000 Australian soldiers who lost their lives in France and have no known grave; Walter ‘Mac’ McGregor among them.