V4783

MAKINSON, John

| Service Numbers: | 2184, 2184A |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | 4 June 1915, Brisbane, Qld. |

| Last Rank: | Private |

| Last Unit: | 9th Infantry Battalion |

| Born: | Dubbo, New South Wales, Australia, 3 December 1891 |

| Home Town: | Dungog, Dungog, New South Wales |

| Schooling: | Not yet discovered |

| Occupation: | Sawyer / Labourer |

| Died: | Killed in Action, Pozieres, France, 23 July 1916, aged 24 years |

| Cemetery: |

No known grave - "Known Unto God" Australian National Memorial - Villers Bretonneux |

| Memorials: | Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour, Villers-Bretonneux Memorial, Woodford Honour Roll |

World War 1 Service

| 4 Jun 1915: | Enlisted AIF WW1, Private, 2184, 25th Infantry Battalion, Brisbane, Qld. | |

|---|---|---|

| 18 Sep 1915: | Involvement Private, 2184, 25th Infantry Battalion, Battle for Pozières , --- :embarkation_roll: roll_number: '15' embarkation_place: Brisbane embarkation_ship: HMAT Armadale embarkation_ship_number: A26 public_note: '' | |

| 18 Sep 1915: | Embarked Private, 2184, 25th Infantry Battalion, HMAT Armadale, Brisbane | |

| 23 Jul 1916: | Involvement Private, 2184A, 9th Infantry Battalion, Battle for Pozières , --- :awm_ww1_roll_of_honour_import: awm_service_number: 2184A awm_unit: 9th Australian Infantry Battalion awm_rank: Private awm_died_date: 1916-07-23 |

Help us honour John Makinson's service by contributing information, stories, and images so that they can be preserved for future generations.

Add my storyBiography contributed by Faithe Jones

Son of John Richard MAKINSON and Catherine nee GIESSELL

Biography contributed by Ian Lang

# 2184 MAKINSON John (Jack) 25th / 9th Battalion

Jack Makinson, a Wiradjuri man, was born in Dubbo in 1891 to John and Catherine Makinson. Jack was the youngest of the six surviving children from a family of ten. When Jack was five years old, his father and eldest brother left Dubbo in search of work. Jack’s mother, Catherine, then died in childbirth and Jack’s father could not be traced. The children still at home were then virtually orphaned. A police officer in Dubbo took the children in until the authorities could find suitable foster placements.

Jack was placed with the family of Mr Dixie Chapman of Dungog, a well-known pioneer of the district north of Maitland NSW. The Chapmans, who had no children of their own, fostered a number of children over the years. Mr Chapman arranged for Jack to be apprenticed to a Mr Fuller. When he was old enough, Jack left Dungog and probably picked up casual labouring work as he travelled up to Queensland. He became a skilled timber worker, working as a sawyer at both Beerwah and Woodford. At some time in his travels, Jack met Miss Violet Mahaffey of Ipswich.

A local story about Jack from the Woodford Historical Society was that he was an itinerant worker who pulled up on his horse outside the Hotel and asked about all the men at the Police Station. When told they were enlisting. He joined them, enlisted, and went back to the Hotel and told them they could have his horse if they wanted it-if not put it out in a paddock. The story may have a grain of truth to it but some of the facts are probably embellishments. Nevertheless, the story perhaps gives a glimpse into Jack’s character.

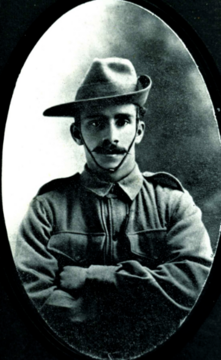

Jack travelled from Woodford to Brisbane by train and attended the recruiting depot in Adelaide Street in the city on 4th June 1915. The regulations regarding enlistment in His Majesty’s Forces at the time explicitly excluded any person who was not of predominantly European heritage which would on the face of it have excluded Jack who had distinct aboriginal features. Nevertheless, he was accepted and the only hint of Jack’s aboriginality was the notation that his complexion was dark. Jack stated his age as 25 and occupation as sawyer. Not having any details of the whereabouts of his siblings, and his father then being deceased, Jack named Mr Dixie Chapman of Dungog as his next of kin. He also stated his home town was Dungog. Once Jack was passed fit, he made his way to the Fraser’s Paddock Camp at Enoggera where reinforcements destined for the 25th Battalion were being outfitted and trained. A photograph of Jack taken at the time shows him to be clean shaven, but once overseas he grew a magnificent black moustache which was commented on.

Jack was placed into the 4th reinforcements of the 25th Battalion and embarked on the “Armadale” in Brisbane on 18th September. Jack allocated 3/- of his daily pay of 5/- to Violet Mahaffey (the Mahaffey family were well known in the Ipswich district), perhaps in the hope that upon his return they would have a tidy sum with which to begin a life together. A witness providing details to the Red Cross noted that at embarkation, Jack wore a ring engraved with his name; possibly a gift from Violet. There were at least two other indigenous men, Towney Kelly and Fred Malthouse, in the 4th reinforcements. Like Jack, their enlistment documents show no mention of them being indigenous, a part from noting that their complexion was “dark.”

Jack and the other 97 men who made up the 4th reinforcements landed in Egypt at Suez and made their way to the infantry depot at Moascar. The original 25th Battalion had been deployed to Gallipoli about the same time as Jack boarded the “Armadale” in Brisbane and the reinforcements continued to train in the Egyptian desert. When the Gallipoli campaign was closed down at the end of 1915, the Gallipoli veterans returned to the camps in Egypt to join the large number of reinforcements accumulating there. At the urging of the British Government, the AIF was doubled in size from two to four divisions. Gallipoli veterans formed an experienced core for new battalions with numbers being made up from the reinforcements who had been cooling their heels in Egypt. On 28th February 1915, Jack was taken on strength by the 25th Battalion but only a few days later was transferred to the 9th Battalion where he kept his regimental number but an “A” was added to differentiate between another soldier in the 9th with the number 2184.

On 27th March 1916, the newly reorganised 9th Battalion boarded a transport in the Egyptian port of Alexandria and sailed to the French port of Marseilles. Upon disembarkation, the battalion was loaded onto railway carriages marked “horses 8 men 20.” The battalion detrained and marched to billets around Strazeele in the Armentieres sector of the Western Front. While practicing brigade and divisional manoeuvres in April, Jack was detached from the 9th Battalion to the ANZAC HQ as part of an escort. The time coincides with much activity by visiting generals, including the overall British commander in France, Douglas Haig, who all came to inspect the new colonial troops. It is most likely that Jack was part of a mounted group that accompanied the top brass as they toured the AIF camps. In selecting Jack for such a high-profile task, the authorities were inadvertently thumbing their noses at the Australian enlistment regulations which were based on race. Once the parades and inspections were over, Jack returned to his battalion where he took his place in the 13th Platoon of “D” company on 26th June.

General Haig planned a big push in the south of the British sector through the Somme River valley for the summer of 1916. It was to be the largest battle of the war so far, and was timed to commence on the 1st of July. The attack was a disaster, with the British suffering 60,000 casualties on the first day, and with little gain in respect of territory. In spite of this, Haig was determined to push on and by the middle of the month his forces were in a position to attack Pozieres. The village of Pozieres half way between Albert and Bapaume, sat on the highest point of that part of the battlefield and as such was great strategic importance. Haig ordered the 1st, 2nd and 4th Australian Divisions south from the Armentieres sector to Albert to take part in the Somme offensive. The 1st Division, which included the 9th Battalion was to be the first into the battle.

The Division moved up into position on 19th July but local commanders argued for a two-day delay to ensure that all preparations were complete. The troops were in position by 10:00pm on 22nd July when the British bombardment of Pozieres village intensified. Just after midnight, the first wave rose up and moved toward the first objective designated OG1. Jack Makinson was part of a bombing party in the first wave. Jack and another man named Snow were right up to the German wire when they were both seriously wounded by a German artillery shell. Another man by the name of Smith dragged both wounded men into a shell crater. Smith stated he was with Jack for some time who had a serious wound to his head. Jack took out a notebook in an attempt to write a note but he was unable to do so. His last words were “I’m done.” Subsequent artillery friendly fire threw up soil and chalk lumps which covered the bodies of Makinson and Snow. When the troops involved in that first charge at Pozieres retired to count the cost, many men where missing. Among those missing was Jack Makinson.

Dixie Chapman back at Dungog would have received the news via telegram that Jack was missing. When Jack’s name appeared in the casualty lists printed in newspapers, Violet Maffey and Jack’s sister, Maude, wrote to the Red Cross Wounded and Missing Enquiry Service seeking information. In due course, the Red Cross were able to contact Private Clarry Smith who could provide the information that was sought. Jack Makinson was finally declared Killed in Action by a court of inquiry in November 1916. Once a death certificate could be provided, Jack’s estate was divided as per his wishes with a one sixth share to each of his siblings.

Jack’s meagre personal belongings, a testament, camera and coat hanger, were parcelled up to be sent to Dixie Chapman. The ship carrying a large number of parcels containing the effects of men who had died was torpedoed of the Scilly Isles and all cargo was lost. Jack Makinson’s remains were never located. In 1938, some 20 years after the end of the First World War, the Australian Government constructed the Australian National Memorial at Villers Bretonneux in France. The memorial was dedicated by the newly crowned King George VI. The memorial records the names of over 10,000 Australian soldiers who lost their lives in France and have no known grave; Jack Makinson among them.

In a more recent tribute, Jack Makinson was commemorated at the Australian War Memorial Last Post ceremony on 3rd June 2025 to signify the end of National Reconciliation Week.