APPELKAMP, Jack

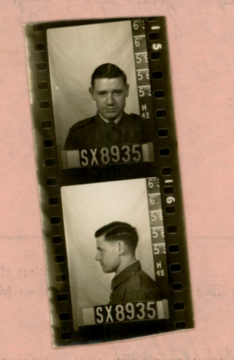

| Service Number: | SX8935 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | 15 July 1940 |

| Last Rank: | Lance Corporal |

| Last Unit: | Not yet discovered |

| Born: | Adelaide, SA, 20 April 1917 |

| Home Town: | Victor Harbor, Fleurieu Peninsula, South Australia |

| Schooling: | Not yet discovered |

| Occupation: | Not yet discovered |

| Memorials: | Ballarat Australian Ex-Prisoners of War Memorial |

World War 2 Service

| 15 Jul 1940: | Involvement Lance Corporal, SX8935 | |

|---|---|---|

| 15 Jul 1940: | Enlisted Adelaide, SA | |

| 15 Jul 1940: | Enlisted Australian Military Forces (WW2) , Lance Corporal, SX8935 | |

| 8 Jan 1946: | Discharged | |

| 8 Jan 1946: | Discharged Australian Military Forces (WW2) , Lance Corporal, SX8935 |

Help us honour Jack Appelkamp's service by contributing information, stories, and images so that they can be preserved for future generations.

Add my storyBiography contributed

Completed by St Ignatius College, Adelaide

Jack Appelkamp was born on the 20th of April 1917 to parents Alfred John Appelkamp and Alice Myrtle Appelkamp (nee. Yon) in Thebarton, South Australia. [1] He was their second son, having an older brother Cleveland, a younger brother named Reginald, and two sisters named Dulcie and Gertie[2].

On the Commonwealth Division of Barker listing from 1943, it records Jack as living in Hindmarsh Road, Victor Harbour, and working as a bootmaker.

Since the document is from 1943 it shows what his address was before he went to war as he would have been unable to change it while in service. As well as this it is able to provide a glimpse into what the workforce at that time consisted of. Namely, men’s jobs leaned more on the laborious side of work including farming, gardening, and carpenters showing the emphasis on men as a working class, an emphasis that would have passed into the pressure to go to war for one’s country, that their ability to work was of better use on the front lines[3]

Jack enlisted on the 15th of July 1940 in South Australia at the age of 23[4]. The extract above of his enlistment form also describes him as having black hair, hazel eyes, and scars on both knees. Additionally, it lists Jack’s next of kin as his father, Alfred John Appelkamp, who resided at 96 Pulsford Road, Prospect.

On the 2nd of February 1941 Jack, along with the other members of the 2/2 MT Reserve Company arrived at Sydney, awaiting a ferry that would carry them to the "HT QX", also known as the Queen Mary. The ship arrived in the Singapore naval dockyards on the 18th of February[5]. The following day on the 19th of February the plans to disembark proceeded and the unit, now in an entirely new country, began their service overseas[6].

Jack began the war as a private and as a member of a motor transport company thus his work mainly revolved around the vehicles in use during the war. The unit diary shows what this work entailed for Jack and his fellow unit members, spending the day inspecting the trucks and preparing them for travel to Malacca and Port Dickson.

Despite the war that constantly surrounded them and the jobs that the unit undertook day after day to assist the soldiers out on the front lines, there were still moments of joy and happiness despite the conflict that surrounded them. The unit diary often mentions the games of football or cricket[7] that the unit was involved in, the use of these games to boost morale during the war and distract from the fear that came with wartime became quite common amongst units.

On October 3rd, 1941, Jack is listed for the first time as a Lance Corporal (L/CL)[8] signifying his promotion from previously being a private. This meant that he would undertake more responsibility than before, and though this may come with its own anxieties the promotion would also come with a great deal of pride, proving both to the recipient, Jack, and those around him that he is both hardworking and a valued serviceman.

On the 16th of February 1942 Jack had been reported missing for direction[9], a month later, however, he was evacuated to hospital after catching dysentery, a common disease seen throughout WW2[10] that could easily be passed on to others, and as such Jack was to recover in hospital rather than potentially spreading the disease to fellow soldiers.

An article in the Pinaroo and Border Times published on the 8th of October 1942 displays the extracts from Jack's last letter to his parents before disappearing. The letter details parts of his life as a driver in Malaya including two incidents in which, though faced with the possibility of death, showed immense courage. The first displayed this and the trust the troops had in each other as he had to repair his vehicle in the dark while artillery and shells were fired around him.

The second incident details a bombing and the terror Jack experienced, hiding as Japanese planes flew overhead; “well it was either the tree or myself that shook”.

But amongst this clear notion of fear in the face of danger a theme of resilience persists through Jack’s humour.

However, along with the newspaper only showing extracts, this letter may not be a fully reliable recount of Jack's experiences as the Australian government implemented censored many soldiers' letters. This, though defended by the want to ensure that information did not fall into the wrong hands in tandem with keeping high morale amongst citizens, meant that Jack potentially lost the ability to reach out to his loved ones at a time of need and as such was isolated even more from those back home.

A year later on the 5th of October 1943, it was reported that Jack had become a prisoner of war[11]. As the entry states him as being "previously reported missing" it can be assumed that he had no contact with his unit between being reported missing and being reported a prisoner of war.

The news of Jack becoming a prisoner of war was like a double-edged sword. While the news was good regarding its confirmation that he was alive, the conditions he was facing would have been largely unknown to his family and though the newspaper lists the report as "[breaking] a long spell of anxiety" it does not mean that all worry would have been eliminated.

Eighteen months after being reported as a prisoner of war it is recorded that Jack had died of dysentery “about May 1944”[12], despite having been reported to be “working healthily” a few months prior[13] This suggests that he would have died of dysentery while in the Japanese camps.

As previously reported being in a camp in Siam[14], Appelkamp most likely would have "died" while working on the Thai-Burma Railway. The conditions of these camps and for the 13000 Australians there working on the railways were horrific. With high mortality rates prisoners were not only on the brink of death themselves but surrounded by thousands of others dying around them[15].

Additionally, illnesses, such as dysentery, ran rampant in these camps. Although it is unclear if Jack recovered from when he was initially hospitalised for the illness the conditions on the railways certainly would not have helped.

On the 16th of September 1945 after it being almost 5 months since he was originally reported dead information had been received that Appelkamp had not died of dysentery and was in fact still alive in Siam as a prisoner of war.[16]

Having contracted dysentery Jack was sent to Nakom Paton[17], was a major hospital camp built in 1944 through the use of native and POW labour along the Thai-Burma railway. The camp was made to impress outside nations, an assurance that prisoners of war were taken care of housing chronically ill and injured soldiers who were unable to work on the railways.

In Reports on Conditions, Life and Work of Prisoners of War in Burma and Siam by Brig C A McEachern the former prisoner of war discusses camp hospitals such as Nakom Paton was. They write:

“These camp hospitals were squalid hovels full of emaciated men suffering from gross malnutrition, dysentery and diarrhoea, pellagra and beri beri and tropical ulcers.”[18]

This extract is telling of the nature of injuries that were commonplace among these men. Soldiers such as Appelkamp suffered indefinitely due to injuries and illnesses that could have been prevented. Appelkamp, who was most likely hospitalised due to his dysentery required what McEachern described as ‘Specific Anti-Disease Measures’, which included vaccines that “were provided in most cases though they did not seem to be particularly effective”. 3

After five years of being in the army, Jack[19], among other members of his unit returned home on the Highland Brigade after being “recovered” from Siam[20], arriving in Fremantle, Melbourne on October 15th, 1945.[21] A year after returning from the war on September 16th,[22] 1946, Jack Appelkamp and Joan Wells, a former member of the Women’s Auxillary Australian Airforce, got engaged. The couple later married on the 23rd of November 1946, at St Cuthbert’s Prospect. he two carried on after the war, raising a family together until Jack’s death on November 28th, 1993, at 76 years old.

References:

[1] FamilySearch.org 2015, Familysearch.org, viewed 13 April 2023, <https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/G3JL-WND>.

[2] Trove 2014, Family Notices - The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA : 1931 - 1954) - 21 Sep 1943, Trove, Trove, viewed 21 May 2023, <https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/48767889>.

[3] National Archives of Australia 2023, Item details, Naa.gov.au, viewed 31 May 2023, <https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/DetailsReports/ItemDetail.aspx?Barcode=7530096&isAv=N>.

[4] National Archives of Australia 2020, Item details, Naa.gov.au, <https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=6402023&S=9&R=0>.

[5] Australian War Memorial 2022, AWM52 10/11/2/1 - [Unit War Diaries, 1939-45 War] 2/2 Australian Reserve Motor Transport Company AIF [Australian Imperial Force] February - May 1941, Awm.gov.au, <https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C2874039>.

[6] National Archives of Australia 2020, Item details, Naa.gov.au<https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=6402023&S=9&R=0>.

[7] Australian War Memorial 2022, AWM52 10/11/2/1 - [Unit War Diaries, 1939-45 War] 2/2 Australian Reserve Motor Transport Company AIF [Australian Imperial Force] February - May 1941, Awm.gov.au <https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C2874039>.

[8] Australian War Memorial 2022, AWM52 10/11/2/3 - [Unit War Diaries, 1939-45 War] 2/2 Australian Reserve Motor Transport Company AIF [Australian Imperial Force] October - December 1941, Awm.gov.au, viewed 13 April 2023, <https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C2874041?>.

[9] National Archives of Australia 2020, Item details, Naa.gov.au, <https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=6402023&S=9&R=0>.

[10] Genge 2020, Malaria and dysentery, Anzac Portal, viewed 18 May 2023, <https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/wars-and-missions/kokoda-track-1942-1943/events/jungle-warfare/malaria-and-dysentery>.

[11] National Archives of Australia 2020, Item details, Naa.gov.au, https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=6402023&S=9&R=0

[12] National Archives of Australia 2020, Item details, Naa.gov.au <https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/DetailsReports/ItemDetail.aspx?Barcode=6402023&isAv=N>.

[13] Trove 2014, Private Casualty Advices - The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA: 1931 - 1954) - 12 Jan 1945, Trove, Trove, <https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/43236570>.

[14] Trove 2014, Private Casualty Advices - The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA: 1931 - 1954) - 12 Jan 1945, Trove, Trove, <https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/43236570>.

[15] Acton, C & National Museum Australia 2015, ‘Burma–Thailand Railway’, Nma.gov.au, <https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/burma-thailand-railway>.

[16] National Archives of Australia 2020, Item details, Naa.gov.au <https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/DetailsReports/ItemDetail.aspx?Barcode=6402023&isAv=N>.

[17] The National Archives 2023, ‘Prisoners of war, Far East: Allied POW camps in Thailand; nominal rolls | The National Archives’, Nationalarchives.gov.uk, viewed 21 May 2023, <https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C11604456>.

[18] Australian War Memorial 2017, AWM54 554/2/1A - [8th Division in Captivity - ‘A’ Force (Burma):] Reports on Conditions, Life and Work of Prisoners of War in Burma and Siam, by Brig C A McEachern, 1942-1945, Awm.gov.au, <https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C2601433>.

[19] Trove 2014, SHIPS ON WAY WITH EX-P.O.W. - 95 S.A. Men On Board MELBOURNE, October 10. - The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA : 1931 - 1954) - 11 Oct 1945, Trove, <https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/48671940>.

[20] National Archives of Australia 2020, Item details, Naa.gov.au, viewed 21 May 2023, <https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/DetailsReports/ItemDetail.aspx?Barcode=6402023&isAv=N>.

[21] National Archives of Australia 2020, Item details, Naa.gov.au, viewed 21 May 2023, <https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/DetailsReports/ItemDetail.aspx?Barcode=6402023&isAv=N>

[22] The Advertiser 2014, Family Notices - The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA : 1931 - 1954) - 16 Sep 1946, Trove, Trove, <https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/35756012>