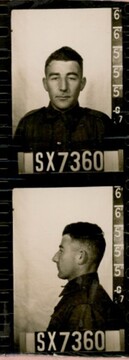

WATSON, Lachlan

| Service Number: | SX7360 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | 1 July 1940 |

| Last Rank: | Sergeant |

| Last Unit: | 2nd/48th Infantry Battalion |

| Born: | Horsham, Victoria, Australia, 12 April 1909 |

| Home Town: | Seaton, Charles Sturt, South Australia |

| Schooling: | Not yet discovered |

| Occupation: | Carpenter |

| Died: | 10 September 1985, aged 76 years, cause of death not yet discovered, place of death not yet discovered |

| Cemetery: | Not yet discovered |

| Memorials: |

World War 2 Service

| 1 Jul 1940: | Enlisted Private, SX7360, Adelaide, South Australia | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Jul 1940: | Enlisted Australian Military Forces (WW2) , Sergeant, SX7360 | |

| 2 Jul 1940: | Involvement Private, SX7360 | |

| 3 Aug 1944: | Discharged Sergeant, SX7360, 2nd/48th Infantry Battalion |

‘One rear-guard action after another’

Victorian born in Horsham on the 12th April 1909, Lachlan lived in Adelaide where, aged 31 he enlisted on the 1st July 1940 to serve in WWII. He was allocated to the newly formed 2/48th Battalion as SX7360. He spent his early days in the cold of the Pavilions, now part of the Royal Adelaide Showgrounds before his battalion headed to Woodside in the Adelaide Hills for preliminary training. Following a brief time of pre-embarkation leave, Lachlan and his fellow members of the 2/48th Battalion then embarked on the Stratheden for the Middle East, on the 7th November 1940, arriving on the 19th December 1940 where the Battalion completed a few months training in Cyrenaica.

During those early days, the men settled into camps, but besides regular army duties was the need to quickly adapt to the locals as John Glenn describes in Tobruk to Tarakan. The ‘Arabs were notorious for thieving – one night they even stole the hessian from around the latrines. Rifles had to be chained to tent poles when not in use, their bolts removed. One morning Privates L. Watson, Donald Carmichael (SX9999), Jack Abbott (SX9323), Edred Wreford (SX9605) and Norman Mellett (SX10164) returned to their tent to find their rifles gone, but in this case Major Bull was the “clifti wallad”, determined to give a starting example of the need for caution.’ Perhaps this was a salutary lesson for all four, as all survived the war.

Lachlan’s battalion was soon involved in intense conflicts where the reputation for being the most highly decorated but decimated battalion was earned. By April ’41 the 2/48th was subjected to heavy German shelling, forcing the men to shelter in the pits they had dug. Glenn describes how at 8:30 the battalion was ordered to move off on foot, ‘passing through the wadis and up the escarpment. The night was very dark; the march, which was over unknown country to the south, had to be made by compass bearing. Locky Watson of the ‘I’ section did a fine job as battalion guide, leading the unit to its destination and at 2:30 am on the 11th April the men were in position, occupying concrete strongposts which had been dug by the Italians.’

Similar conditions were also described in Darren Paech’s book, Adelaide to Alamein where in October’42 he describes how a severe dust storm called a khamsin had risen over the desert ‘blotting out the death and destruction of the surrounding area and making it difficult for the reconnaissance patrol consisting of Major Tom Scott, Captain Basil King, Lieutenant Don Wallis, Sergeant Jack Glenn and Lachlan Watson, to carry out these tasks. They had to find and mark the route that the 2/48th Battalion would take to the start line 1,500 yards north of Trig 29 that night. The rest of the men, filthy and tired, remained below ground and tried to relax as they waited for the order to move out again.’

Glenn describes the same incident where on the morning of the 30th October, the khamsin rose and blotted out the sight of “man’s inhumanity to Man’. It spread like a great shroud over Egypt, half burying the dead, and hid for a brief moment the hate and passion of war. And under its cover plans were laid for the final blow by the 2/48th Battalion.’ Sergeant Watson was in the small group that had moved forward at dawn, north of Trig 29, to reconnoitre the route over which the battalion would move that night.’ What faced the men was a tremendous task. ‘The battalion had been fighting hard for six days and had suffered many casualties. Tonight, it faced its most difficult task with depleted ranks, the total strength of the rifle company being down to 213. We thought of ourselves as being few enough then. But surely even the bravest among us would have shuddered if they could have known to what a weary handful we would be reduced by morning..’

That hard, relentless fighting came with some relief in Christmas ’42 where a rest period of a couple of days was allowed as a prelude to the troops’ third Christmas in Palestine, to be followed by company training, and inoculations and vaccinations, until New Year’s Day when a donkey race meeting was held. Sergeant Watson was one of the Stewards of the six events including the ‘Hammer Handicap’ and ‘Shammama Shambles’ where donkeys with imaginative names like ‘Rommel out of Africa by Easter’ and ‘Latrine out of Paper by Austerity’ raced, backed by the soldiers with their hard-earned wages.

Finally, the remnants of the 2/48th returned to Adelaide in March ’43. The local News proudly announced ‘With 2½ years of history-making fighting behind it, the 9th Division A.I.F. received a warm welcome on its return to Australia. One of its South Australian battalions has won three Victoria Crosses and 60 other decorations and awards-more than any other A.I.F. unit.’

The reporter did a magnificent job of interviewing returnees and putting some of the stories into print. These included reflections from Sergeant Watson. ‘The originals of the Battalion arrived in the Middle East when Jerry was rolling back the garrison in Libya after most of the troops had been transferred to Greece. Sergeants Lachlan Watson, of Adelaide. and Jack Glenn, of Victor Harbor, said that they first went into action near Benghazi and had to fight one rear-guard action after another. They would fight for a few hours, then withdraw. That went on for five days and nights. They snatched sleep at odd intervals. Then, in a raging sandstorm, they withdrew into the fortress of Tobruk, where they met the battalion, which had gone to Tobruk "for training". For the next 7½ months they proved to the world that the Hun could be stopped. In the early months before the Navy's "ferry service" had got into its stride, they lived on bully beef and biscuits. Tobacco was a problem. They smoked all the Italian cigars left behind in the dugouts. Butts were rolled into new cigarettes, and the butts of those kept and smoked again. Their equipment consisted mainly of captured weapons. The Italians had taken the sights off their artillery, but that did not beat the Australians. They judged range by sighting on the telegraph poles up the Bardia road, deflected so many inches to the right or left--and did a lot of damage.’

Lachlan was eventually discharged in August, ’44. Aged 76, he died on the 10th September 1985.

Researched and written by Kaye Lee, daughter of Bryan Holmes SX8133, 2/48th Battalion.

vvvvvvvvvvvvvv

Submitted 22 April 2022 by Kaye Lee