MCNELLEE, Shadrac

| Service Number: | 2689 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted: | Not yet discovered |

| Last Rank: | Private |

| Last Unit: | 13th Infantry Battalion |

| Born: | Budgong, New South Wales, Australia, 4 February 1886 |

| Home Town: | Kangaroo Valley, Shoalhaven Shire, New South Wales |

| Schooling: | Not yet discovered |

| Occupation: | Farmer |

| Died: | Killed in Action, France, 11 April 1917, aged 31 years |

| Cemetery: |

No known grave - "Known Unto God" |

| Memorials: | Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour, Kangaroo Valley War Memorial, Nowra Soldiers Memorial, Villers-Bretonneux Memorial |

World War 1 Service

| 7 Oct 1916: | Involvement Private, 2689, 45th Infantry Battalion , --- :embarkation_roll: roll_number: '19' embarkation_place: Sydney embarkation_ship: HMAT Ceramic embarkation_ship_number: A40 public_note: '' | |

|---|---|---|

| 7 Oct 1916: | Embarked Private, 2689, 45th Infantry Battalion , HMAT Ceramic, Sydney | |

| 11 Apr 1917: | Involvement Private, 2689, 13th Infantry Battalion, --- :awm_ww1_roll_of_honour_import: awm_service_number: 2689 awm_unit: 13 Battalion awm_rank: Private awm_died_date: 1917-04-11 |

Woodchop Champion and Axeman

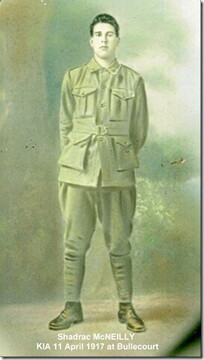

A farmer by profession and a champion woodchop axeman Shadrac McNellee was the son of James and Mary McNellee of Budgong (near Nowra). Friends and later battalion mates knew him as Peter.

McNellee enlisted in Kiama at the age of 30 on 8 June 1916 along with Jack Huxley, George Ditton, Bill Lidbetter and Oswald McClelland. He embarked on 7 October 1916 on the HMAT Ceramic from Sydney. George Ditton and Jack Huxley were also on this embarkation. Eventually to join D Coy of the 13th Battalion McNellee had been originally assigned to the 45th Battalion like many of the other Kangaroo Valley servicemen.

He joined the battalion on 18 March 1917 and spent his first weeks of the war repairing roads and digging cable trenches at Favreuil and Noreuil. He was one of a re-inforcement contingent of 4 officers and 25 other ranks that was added to the battalion to bolster its strength for the pending campaign that has come to be known as First Bullecourt. April 1917 came in very cold with sleet and heavy snow.

Officers reconnoitred the ground in front of Riencourt on 7 April with the knowledge that the 13th Battalion was to be engaged in the action. Ominously, this attack was a marked departure from the strategies of previous assaults as there was to be no preliminary artillery bombardment. Instead, tanks to be used as mobile artillery in support of the infantry.

On the evening of 9 April McNellee was marched with the battalion from Favreuil to Noreuil arriving at 1am. They were in position by 0430hrs the following morning when word was received that the attack had been cancelled. The 12 British tanks that were to accompany the attack and neutralise the machine guns did not turn up due to mechanical breakdowns. The men were now forced to withdraw from the start line through the snow under full view of the enemy. With the element of surprise now lost and the attack re-scheduled for the following morning a military disaster was assured. Tired, disappointed and more pessimistic than ever of High Command the 13th filed back to the start point at the Railway Cutting the next morning.

McNellee hopped over at 0445hrs on 11 April. According to the 13th Battalion Diary:

“As soon as they left the shelter .. losses from the shell fire commenced .. the battalion came under heavy machine gun fire which became more intense at the first wire and officers and men fell fast.

At about 7.30am the Germans counter-attacked by bombing down a communications trench. At 10.45am heavy bomb attacks by the Germans were started from the left and right of both objectives, also down a communications trench … these attacks were very severe.

Attempts to call up an artillery barrage ... failed. The men tried to get back over the open ground under a fearful machine gun and rifle fire; the losses were extremely heavy. Shortly after noon the position was entirely evacuated.”

The British infantry division alongside the Australians were instructed to attack at the sight of the tanks in Bullecourt. With the failure of the tanks they did not “hop over” at all, and so the Australians had the undivided attention of the Germans all morning. Their own artillery had also ignored repeated SOS flares put up by the infantry.

The remnants of the battalion were withdrawn after nightfall to Noreuil where a roll call confirmed the appalling losses – 25 killed, 367 missing and 118 wounded. Half the battalion strength had been destroyed in a morning.

The complete faith in the tanks had been absurd, as were intelligence statements made as to the weakness of the enemy. The Commanding Officer of the 13th Battalion placed the miscarriage of the attack squarely on the failure of the tanks. Those that did participate were quickly taken out of action by one anti-tank gun firing over open sights from 500 yards away. The gun was eventually destroyed by the gallant efforts of the infantry but too late to sway the fortunes of the battle. The Australian historian Charles Bean wrote:

The (Australians) had been employed in an experiment of extreme rashness .. persisted in by the army commander after repeated warnings ...”

McNellee was firstly to be listed amongst those 367 missing in action by 11 April. However, there were eye witness accounts that McNellee was badly wounded by shrapnel in the right hip around daybreak that morning. He had been standing at the back of the trench which they had taken from the enemy during the advance, about 900 yards of the German Hindenburg Line.

Pte. Ernest Mather was also wounded in this engagement and said in several accounts that he lay on a stretcher alongside McNellee at the Casualty Clearing Station that morning. He told the Red Cross they had spoken all day and noted:

“He was wounded in the hip but seemed pretty right and was quite cheerful.”

Mather also said McNellee was evacuated towards Rouen on the morning of 13 April but he did not see him afterwards. How his body came to be “missing” is unknown given that he was being evacuated from the Casualty Clearing Station with others.

A number of those posted as missing were subsequently determined to have been taken prisoner during this desperate action. Os McClelland was one such case, captured after his position had become untenable with the exhaustion of their ammunition supplies and the isolation of his platoon.

A Court of Inquiry held in October that year conveniently determined that McNellee had been killed in action at the time he went missing. His death was confirmed in the casualty list of the Sydney Morning Herald on 20 November 1917. Shadrac McNellee has no known grave and so his name appears on the Villers-Bretonneux Memorial in France.

He had been killed on his first day in action.

Submitted 10 May 2022 by Geoffrey Todd

Biography contributed by Sharron Haenga

Shadrach McNeilly, his birth name, was born on 4 February 1886 in Budjong, New South Wales, the son of Mary Lees and James McNeilly. Somewhere along the way he acquired the name of 'Peter'. He had 11 brothers and 9 sisters. He was the youngest in his family and the only sibling to enlist, so it must have struck hard in his parent's hearts when they received correspondence of his death. He died on 11 April 1917 in Bullecourt, Pas-de-Calais, France, at the age of 31, and was memorialised in Villers, Aisne, France.